Study Examines Gadolinium Deposits in MS Patients’ Brains, But Still Can’t Determine Relationship with Disease Severity

Written by |

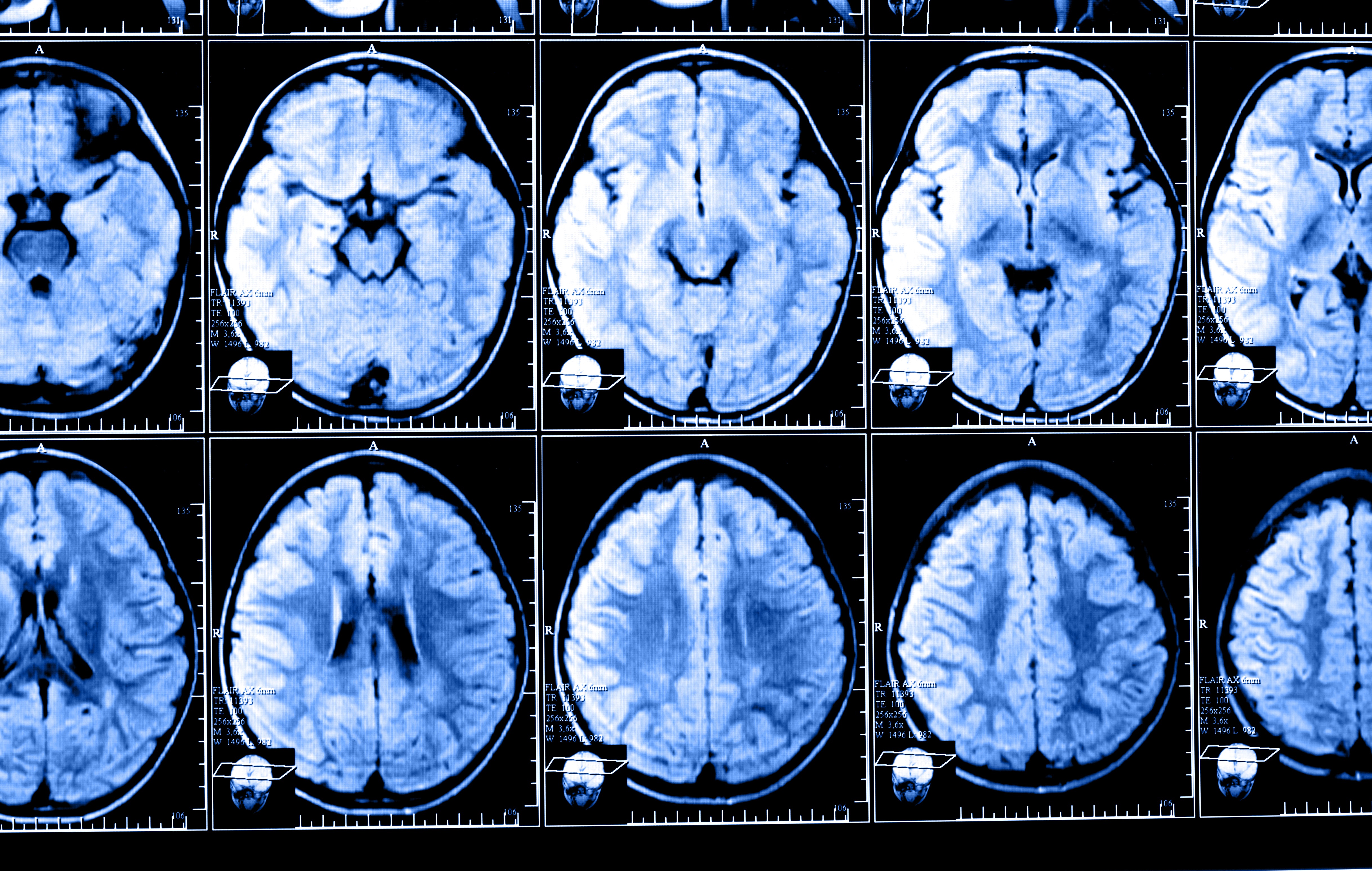

The use of gadodiamide, a gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) often used to help clinicians visualize brain structures in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, leads to the accumulation of gadolinium in certain regions of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients’ brains early in the course of the disease, a study has found.

However, the relationship with disease severity remains unclear.

Those findings, in the study “Cumulative gadodiamide administration leads to brain gadolinium deposition in early MS,” were published recently in Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN).

In its natural state, gadolinium is highly toxic. For that reason, in order to be used in clinical practice as a contrast agent, gadolinium needs to be joined with other molecules, giving rise to different types of GBCAs.

There has been controversy in the MS community about the use of GBCAs as contrast agents. That is primarily because some of these agents are associated with gadolinium accumulation in the brain of MS patients who frequently undergo MRI brain scans to monitor the progression of their disease, raising the concern of toxicity and disease worsening.

Due to these concerns, four GBCAs already have been banned in Europe, and in 2017 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a recommendation stating the use of GBCAs should be kept to a minimum.

Several studies have shown that patients who frequently undergo brain scans, and are injected with contrast agents, develop gadolinium depositions in the brain. However, none of those studies monitored long-term brain alterations associated with the use of GBCAs in MS patients.

In the recent study, a group of researchers from the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo, New York, examined the progression of brain alterations occurring in MS patients since experiencing their first symptoms, up to five years after being diagnosed.

The large-scale longitudinal study involved 203 MS patients, who were followed at the Buffalo Neuroimaging Analysis Center (BNAC) of the University at Buffalo from 2003 to 2016. All patients had received identical doses of gadodiamide during each MRI session performed at the Buffalo General Medical Center. The study also included 262 healthy individuals used as controls.

At a mean follow-up period of 55.4 months (4.5 years), study participants received an average of 9.2 injections of gadodiamide.

Results showed that at follow-up, almost half of the MS patients (49.3%) had areas of high-gadolinium intensity in the dentate nucleus (a brain region responsible for controlling voluntary movements and cognition), while none of the controls had the same type of high-intensity gadolinium depositions in the same region.

In other brain regions, such as the globus pallidus (a region that controls voluntary movements), MS patients also had areas of gadolinium deposition of higher intensity compared to controls.

However, investigators failed to find a clear association between the presence of high-intensity gadolinium depositions and MS severity.

Interpreting the findings

Based on the results, the team concluded that brain “gadolinium deposition in early MS is associated with lifetime cumulative gadodiamide administration, without clinical or radiologic correlates of more aggressive disease,” they wrote.

“This study is one of the first to investigate the longitudinal association between well-established clinical and MRI outcomes of disease severity and gadolinium deposition,” said Robert Zivadinov, MD, PhD, said in a press release written by Ellen Goldbaum. Zivadinov is a professor in the department of neurology, director of the BNAC, and lead author of the study.

“The study didn’t find any correlation between deposition in the brain and clinical or MRI outcomes, such as accumulation of lesions, brain atrophy or disease severity, at least in the first five years of the disease,” Zivadinov added. “Over the 4.5 years of follow-up, we didn’t find that GBCA deposition contributed to patients being more disabled.”

Nevertheless, researchers did find that MS patients who had received more than eight injections of gadodiamide tended to have a higher number of brain lesions, as well as more severe brain atrophy (shrinkage), compared to those who had less than eight gadodiamide administrations.

“Therefore, we cannot completely rule out that gadolinium deposition may have an impact on disease progression or clinical outcome,” Zivadinov said, adding that the findings from the study “should be incorporated into a risk-versus-benefit analysis when determining the need for GBCA administration in individual MS patients.”

Interestingly, researchers also found that male patients were more prone to have gadolinium depositions than female patients. This unusual finding, according to Zivadinov, might be because men typically receive higher doses of contrast agents, as the dose is based on the individuals’ body weight, which may increase their chances of developing gadolinium depositions.