Discovery of Brain-membrane Immune Cell May Advance MS Treatment Work

Written by |

The discovery of a new type of immune cell in the membranes covering the brain is likely to advance understanding of the immune system’s impact on the brain, a study says. It could also lead to new treatments for multiple sclerosis (MS) and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Researchers knew the immune cell existed in organs that create barriers between our body and the outside world, such as the skin, gut, and lungs. The cells’ discovery in the brain is not only surprising, but also suggests the cells may play a role in communications between the microbes that inhabit other parts of our bodies and the brain.

The study, “Characterization of meningeal type 2 innate lymphocytes and their response to CNS injury,” was published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

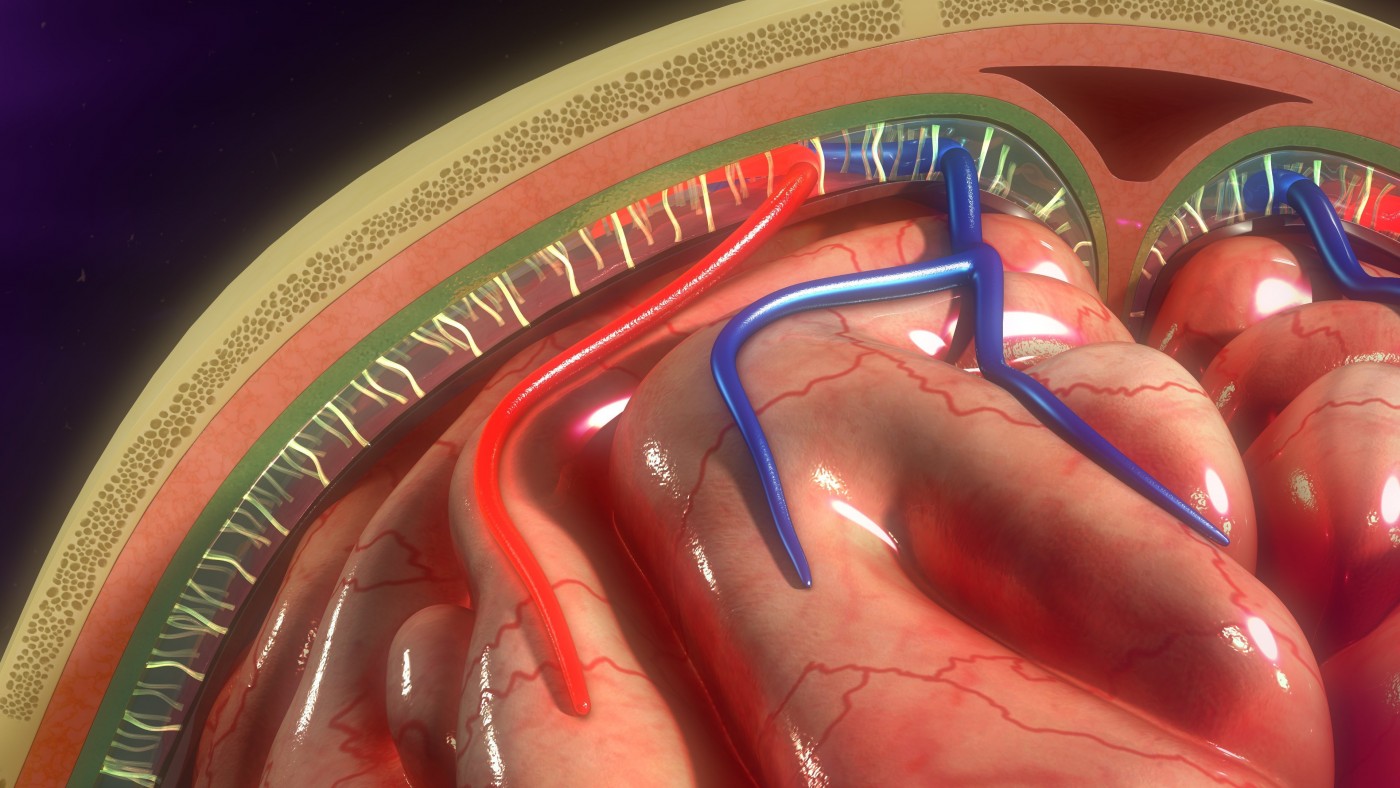

It is the second time in a year that the research team at the University of Virginia (UVA) School of Medicine has stepped into the spotlight. Last year, they discovered that the brain is lined with lymph vessels that scientists did not think existed there. The finding suggested that lymph vessels were a route for immune cells to move into the brain.

As the researchers did additional lymph-vessel studies, they discovered a new type of cell known as a type 2 innate lymphocyte. The cells were not in the lymph vessels, as one might imagine, but on the outside, surrounding the vessels.

In mouse experiments, the team found that the cells become activated after a spinal cord injury. When they added the cells to the brains of mice which lacked a factor crucial to the cells’ activation, they noticed improvement in recovery from a spinal-cord injury.

“This all comes down to immune system and brain interaction,” Jonathan Kipnis, chairman of UVA’s Department of Neuroscience and director of its Center for Brain Immunology and Glia, said in a press release.

“The two were believed to be completely not communicating, but now we’re slowly, slowly filling in this puzzle,” added Kipnis, the study’s senior investigator. “Not only are these [immune] cells present in the areas near the brain, they are integral to its function. When the brain is injured, when the spinal cord is injured, without them, the recovery is much, much worse.”

The team believes the cells do a lot more than just aiding in spinal-cord repair. Since the same type of cell is also found in the gut, they think the cells could be crucial to gut-brain communication. Several other studies have noted the importance of gut microbes to brain health.

“These cells are potentially the mediator between the gut and the brain,” Kipnis said. “They are the main responder to microbiota changes in the gut. They may go from the gut to the brain, or they may just produce something that will impact those cells. But you see them in the gut and now you see them also in the brain.”

He added: “We know the brain responds to things happening in the gut. Is it logical that these will be the cells that connect the two? Potentially. We don’t know that, but it very well could be.”

Although a lot more research needs to be done to understand what the cells do in the meninges, or brain membranes, the team is convinced they are involved in a range of neurological conditions.

“The long-term goal of this would be developing drugs for targeting these cells,” said Sachin Gadani, lead author of the study. “I think it could be highly efficacious in migraine, multiple sclerosis and possibly other conditions.”