MS Australia funds project that explores EBV, MS genetic risk link

Study will ID people who don't have MS, but carry genetic risk for it

Written by |

A research project to explore the genetic connection between the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and the risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) has been awarded a $24,400 incubator grant by the nonprofit MS Australia.

Titled “A novel use of human genetics to recruit participants for MS research,” the study will identify people who don’t have MS, but carry varying levels of genetic risk for the disease. Researchers will then compare the biological traits of those with a high genetic risk with low-risk individuals to better understand early factors linked to developing MS.

“If we identify people who are at risk of developing MS, we need to consider how – and whether – to share that information, particularly as this information may not yet be clinically actionable,” project leader David Stacey, PhD, and researcher at the University of South Australia, said in a university news story. “This study will explore those ethical, legal, and social questions to guide how future studies approach personal genetic risk.”

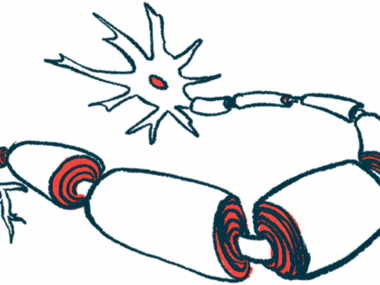

MS develops when the immune system mistakenly attacks the myelin sheath, a protective coating that surrounds nerve fibers and helps transmit electrical signals efficiently. Damage to this sheath leads to gradual nerve fiber degeneration and a wide range of MS symptoms.

The risk of MS

The risk of developing MS is shaped by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. One key environmental trigger is infection with EBV, which causes infectious mononucleosis, often called the “kissing disease.” Despite this link, most people infected with EBV never develop MS.

The connection is thought to stem from a structural similarity between certain EBV proteins and those in the brain. As a result, the immune system’s response to the virus may mistakenly target healthy brain tissue. This suggests that individual differences in the immune response to EBV could play a critical role in developing MS.

“For many years, we’ve known that the Epstein-Barr virus is a likely precursor for MS. But because the virus affects up to 90% of the population, it’s difficult to pin down why some people go on to develop MS while others don’t, ” Stacey said.

This project will calculate MS genetic risk scores for more than 1,000 participants in South Australia who don’t have an MS diagnosis, and compare biological traits related to EBV, MS, and immune-related measures in people with either a low or high genetic risk.

Genetic risk will be performed using a method called recall by genotype, or RbG. It involves identifying people from existing research studies or biobanks based on their specific genetic characteristics, or genotype, and inviting them back for more detailed investigations. This way, instead of recruiting participants based on MS, RbG starts with the genetic data, selecting participants with variants associated with the risk of developing the disease. As the participants don’t have MS, any differences found will likely reflect early biological mechanisms that may contribute to developing the disease, rather than changes caused by the disease, according to the researchers.

“It’s like studying the immune system’s blueprint before the disease starts,” Stacey said in a separate press release.

The project also seeks to test the feasibility of using RbG in MS research and set the basis for a larger study. For that, the researchers will refine methods for selecting and inviting participants based on genetic risk; explore the ethical, legal, and social implications of using genetic information for research recruitment; and optimize laboratory methods to measure immune and viral markers.

“By focusing on people who don’t have MS, but carry different levels of genetic risk, we’re hoping to uncover early immune system changes that might help explain who develops MS and why,” Stacey said. “It could also help identify early biological markers that show when MS might be starting to develop. This may lead to earlier detection, new treatments, or even prevention.”