Myelin damage scrambles brain communication, mouse study finds

Results shed light on role of protective coating in key brain signaling circuit

Written by |

Myelin, the protective coating that helps nerve signals travel quickly and efficiently, also plays a key role in the precise timing of communication between brain cells, a new study from scientists in the Netherlands shows.

In a mouse model, the researchers found that the loss of myelin disrupted the coordination of signals between different brain regions, impairing the brain’s ability to process information accurately.

The findings may shed new light on diseases, including multiple sclerosis (MS), that are marked by damage to myelin.

According to Maarten Kole, PhD, coauthor of the study at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, missing myelin resulted in slower and less consistent signal transmissions in the brain.

“You could compare it to a barcode in the supermarket: The scanner only recognises a product if you scan the entire barcode,” Kole said in a news story from the institute detailing the findings.

“If you miss the first piece of myelin, then you’re essentially skipping the first black stripe of the barcode. Because of this, you can’t scan the right product anymore,” Kole said.

The study, “Layer 5 myelination gates corticothalamic coincidence detection,” was published in the journal Nature Communications.

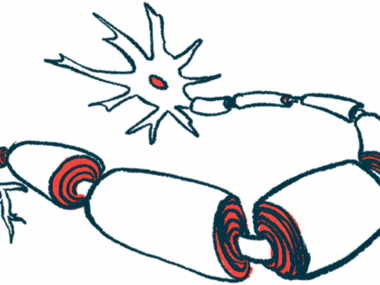

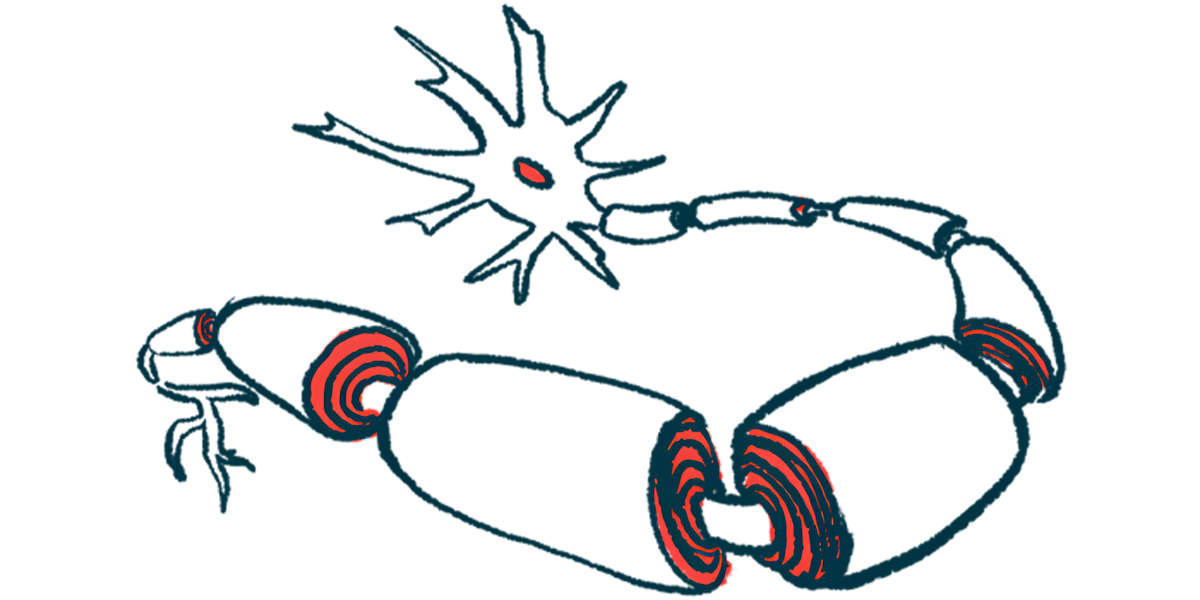

Nerve cells contain long, wire-like projections called axons to transmit electrical signals. Many axons are wrapped in myelin, a fatty substance that protects axons and helps them send signals much faster, much like insulation around an electrical wire.

Although myelin is known to increase the speed of electrical signals, its specific roles in different brain circuits are still being uncovered.

Mouse model used to examine effects of myelin loss in brain

In this study, the research team used a mouse model to examine how myelin loss affects communication between the cortex — the brain’s outer layer, involved in complex functions such as thinking and decision-making — and the thalamus, a deep brain structure that helps process and relay sensory information.

The scientists focused on a group of nerve cells located in the fifth layer of the cortex. These neurons send long projections to the thalamus and play an important role in coordinating activity between the two regions.

“We actually understand these cells very well, but we didn’t know which role myelin played in the process of transferring information to the thalamus,” Kole said.

To study the effects of myelin loss, the researchers used a well-established mouse model in which animals are fed cuprizone, a compound that selectively damages myelin. In these mice, myelin loss occurred primarily in a short segment of the axon close to the nerve cell body, which is the compartment that houses the cell’s DNA.

Nerve cell bodies comprise the brain’s grey matter, and in MS, grey matter damage is often associated with cognitive issues.

The team found that damage to myelin in this specific segment disrupted the timing and reliability of nerve signals traveling from the cortex to the thalamus. Rather than simply slowing signals down, myelin loss made their arrival less precise, particularly during rapid bursts of activity.

“We had anticipated [slower nerve signaling], because myelin is known to be essential for fast signal transmission, but what was new to us was that we lost the first wave of signals entirely,” Kole said.

Mice in study had trouble telling when whiskers were touched

One key function of communication between the cortex and the thalamus is mediating coincidence detection — the brain’s ability to distinguish between stimuli that happen very close together in time.

In mice, this can involve telling the difference between two brief touches of the whiskers against an object versus one longer brush. The corticothalamic loop helps amplify signals so that the brain can distinguish between individual stimuli.

The researchers found that myelin loss reduced the accuracy of this signal amplification, impairing coincidence detection. While signals were still transmitted, their timing was less consistent, making it harder for the brain to correctly interpret closely spaced sensory inputs.

Our present findings may lead to exciting new avenues to identify how myelin patterns, and adaptive myelination, are involved in computational processing and mediating complex behaviors.

“We saw that this amplification is still happening, but less accurately. Because of that, the communication loop between these two brain areas is disrupted, and the brain loses track. The mouse can still feel something with its whiskers, but it can’t exactly identify when or what,” Kole said.

Overall, according to the researchers, these findings highlight a previously unknown role for myelin in maintaining the precise timing of brain signals, which could have significant implications for understanding diseases such as MS.

“Our present findings may lead to exciting new avenues to identify how myelin patterns, and adaptive myelination, are involved in computational processing and mediating complex behaviors,” the scientists concluded.