Gut bacteria may trick immune system into triggering MS: Mouse study

Researchers say findings could pave way for new treatment approaches

Written by |

- Inflammatory gut bacteria mimicking myelin may trigger and worsen multiple sclerosis.

- Immune cells mistakenly attack myelin due to structural similarities with bacterial proteins.

- Targeting gut bacteria could lead to new therapeutic approaches for multiple sclerosis.

Inflammatory gut bacteria that carry proteins structurally similar to myelin, a protective layer surrounding nerve fibers that is damaged in multiple sclerosis (MS), may trigger the development and progression of the disease, according to a new study done in mouse models.

The findings may pave the way toward new approaches to treat MS by targeting gut bacteria, researchers said in the study, “Antigen-specific activation of gut immune cells drives autoimmune neuroinflammation,” which was published in Gut Microbes.

“In the future, if we work with different bacteria that actively calm the immune system instead of triggering it, we might be able to train immune cells to tolerate the myelin sheath and not attack it,” Anne-Katrin Pröbstel, PhD, a professor at the University of Basel and the University of Bonn and co-author of the new study, said in a university news story.

Composition of bacteria living in intestine can be abnormal in MS

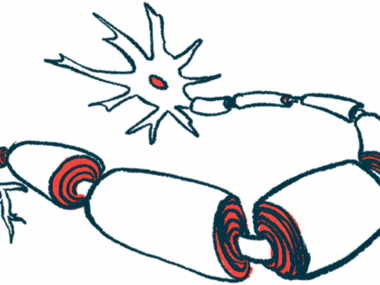

Myelin is a fatty substance that helps nerve cells send electrical signals. In MS, the immune system mistakenly attacks myelin in the brain and spinal cord, disrupting nerve signaling and ultimately leading to the development of disease symptoms. Exactly what causes the immune system to launch this accidental attack remains poorly understood, however.

A growing body of evidence suggests that the composition of bacteria living in the intestine is abnormal in MS. Gut bacteria and the metabolites they produce are known to interact with immune cells, and the presence of pro-inflammatory gut bacteria in MS patients has led some scientists to speculate that gut bacteria may play a key role in driving the disease.

“We know that the intestinal [bacteria] influences the immune system, but the mechanisms related to MS are not fully understood,” Pröbstel said.

One particular hypothesis is a phenomenon known as molecular mimicry. The basic idea is that certain pro-inflammatory gut bacteria produce proteins structurally similar to those found in myelin. When immune cells attack these inflammatory bacteria, they use molecular weapons, such as antibodies, that target the bacterial proteins. However, due to the structural similarities, these antibodies also inadvertently target myelin, leading to an immune attack against the body’s own tissue.

Researchers engineered Salmonella strain to produce a myelin protein

In this study, scientists aimed to conduct proof-of-concept tests to determine if this hypothesis is true. To that end, they conducted a series of experiments using mice genetically engineered to have immune cells targeting myelin, serving as a model for MS.

The researchers then engineered an inflammatory strain of Salmonella bacteria to produce a myelin protein. For comparison, the researchers also generated bacteria producing ovalbumin, the main protein in egg whites. These protein-laden bacteria were then given to the MS mice orally to allow them to colonize their guts.

Results showed that bacteria with the myelin protein led to faster disease progression and worse motor function in MS mice. The pro-inflammatory bacteria producing the egg protein also slightly increased disease activity, but to a much lesser extent.

The researchers then conducted similar experiments using germ-free mice, or mice engineered to have no gut bacteria of their own. In these animals, bacteria with the myelin protein triggered MS-like disease, but bacteria expressing the egg protein did not.

Our findings demonstrate that gut-restricted bacteria expressing a [myelin protein] can initiate local immune activation leading to subsequent [brain and spinal cord] inflammation, a process that is influenced by the bacterial context.

Analyses of the mice’s immune cells showed evidence of more myelin-targeting B-cells and T-cells in mice with myelin-producing bacteria. Collectively, these data support the idea that inflammatory bacteria producing myelin-like proteins could be a trigger for MS initiation and progression, the researchers said.

The scientists also wanted to know if different types of bacteria would trigger different effects. To that end, they engineered Escherichia coli — a noninflammatory bacteria commonly found in healthy digestive tracts — to produce the same myelin or egg proteins, then repeated their experiments.

They found that E. coli producing the myelin protein triggered slightly more aggressive disease than E. coli that produced the egg protein, but the impact of this noninflammatory bacteria was markedly less dramatic than that of the inflammatory Salmonella.

“Our findings demonstrate that gut-restricted bacteria expressing a [myelin protein] can initiate local immune activation, leading to subsequent [brain and spinal cord] inflammation, a process that is influenced by the bacterial context,” the researchers concluded, adding that this study “carries broader implications for the development of [gut bacteria]-based therapeutic approaches.”