Multiple Sclerosis: How Can MRI Measurements be Improved in Trials?

Written by |

A study from German researchers might help to determine how multiple sclerosis is assessed in treatment trials. Published February 6 in the journal PLoS ONE, the study is titled “Regression to the Mean and Predictors of MRI Disease Activity in RRMS Placebo Cohorts – Is There a Place for Baseline-to-Treatment Studies in MS?”

A study from German researchers might help to determine how multiple sclerosis is assessed in treatment trials. Published February 6 in the journal PLoS ONE, the study is titled “Regression to the Mean and Predictors of MRI Disease Activity in RRMS Placebo Cohorts – Is There a Place for Baseline-to-Treatment Studies in MS?”

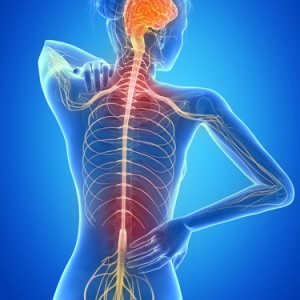

Multiple sclerosis is one of the most common degenerative neurological conditions that affects young adults worldwide. MS can occur at any age, although generally diagnosis occurs between the ages of 20 and 40. The disease is caused by an autoimmune response — an attack on the myelin that wraps around nerve cells and allows them to conduct impulses. This results in unpredictable damage to the nervous system, known as lesions. Symptoms such as loss of movement, numbness, tingling, pain, loss of eyesight and cognitive impairment may result.

In Phase 2 clinical trials for multiple sclerosis treatments, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis is conventionally assessed by observing gadolinium-enhancing (GD+) lesions and T2 lesions through the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A GD+ lesion is a bright spot on the MRI that shows that there is damage to the nervous system. T2 lesions are also bright spots showing damage, and this is a common way for looking at the loss of myelin in multiple sclerosis.

Not very much is known about what can predict lesion development, which could be crucial to understand what treatments work in these studies. Specifically, a measurement known as “regression-to-the-mean” is important. This is a statistical method that accounts for measurements that are extremely variable, such as the unpredictable lesions found in multiple sclerosis.

[adrotate group=”4″]

According to the authors, the current study sought to quantify regression-to-the-mean and identify predictors of MRI lesion development.

The researchers analyzed data from 21 Phase-2 and Phase-3 trials. They extracted data about the development of T2 and GD+ after 6 months (phase-2 trials) or 2 years (phase-3 trials).

They observed that 39% of the study participants did not have a new T2-lesion after 6 months and 19% did not have a new T2-lesion after 2 years. The best way to predict new lesions at 6 months was found to be the average number of baseline GD+ lesions.

The authors concluded that “Baseline GD-enhancing lesions predict evolution of Gd- and T2 lesions after 6 months and might be used to control for regression to the mean effects.” The measurement may be helpful for reducing the variability that occurs in clinical studies of multiple sclerosis treatments. Overall, the study emphasizes the importance of taking measurements at the beginning of the study, prior to any treatment, to predict later study outcomes.