Can Epstein-Barr virus cause multiple sclerosis?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease thought to arise from a combination of environmental and genetic factors. Over the past decade, a growing body of evidence has identified Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a member of the herpes virus family, as a major environmental risk factor for MS.

While most people with EBV never develop MS, virtually all people with MS show evidence of a past EBV infection. This has led many experts to believe that EBV is necessary for MS to develop, but not sufficient on its own. Instead, EBV appears to act as a viral trigger that interacts with other MS risk factors to initiate the disease process.

What is Epstein-Barr virus?

EBV, also known as human herpesvirus 4, is one of the most common viruses worldwide. Estimates indicate that at least 90% of adults worldwide have been infected at some point in their lives.

EBV infection often occurs in childhood, and is usually asymptomatic or with symptoms similar to a mild cold. For this reason, most people never know they’ve had it.

When symptoms do occur, EBV is best known as the cause of infectious mononucleosis, commonly known as mono or the “kissing disease,” which may be accompanied by symptoms such as fever, fatigue, sore throat, rash, and body aches.

EBV primarily infects B-cells, immune cells responsible for producing antibodies that help combat potentially harmful foreign substances.

In the human body, the life cycle of EBV can be divided into two phases: the lytic phase, when it is actively reproducing and is most likely to cause symptoms; and the latent phase, where it lies dormant inside B-cells for the rest of a person’s life. It is possible for the virus to reactivate after entering the latent phase, which may or may not cause symptoms.

Is EBV associated with MS?

A connection between EBV and MS has been suspected for decades. Research has consistently shown that people with MS almost always have antibodies against EBV — an indicator of a prior infection — and often at higher levels than people without MS.

A history of infectious mononucleosis has also been associated with an increased risk of developing MS.

Despite the abundance of earlier research, it had been difficult to establish whether EBV actually causes MS, rather than simply being associated with the disease.

Two landmark studies published early in 2022 — one from Harvard University and one from Stanford University — have provided compelling evidence supporting a causal link between EBV and MS.

Harvard study: EBV as a leading MS risk factor

In a large, long-term study, a team of researchers at Harvard identified the most definitive link between EBV and MS risk to date.

In collaboration with the U.S. military, Harvard researchers tracked the health of millions of active-duty service members over a period of more than 20 years. This included the collection of blood samples to look for EBV antibodies over time.

Key findings included:

- EBV infection increased the risk of developing MS by 32 times, making it the strongest known risk factor for the disease

- 800 of 801 individuals who developed MS had been infected with EBV before MS onset

- MS symptoms appeared a median of 7.5 years after EBV infection

- levels of neurofilament light chain, a biomarker of nerve cell damage, were increased in service members who later developed MS, but only after they became infected with EBV

- no other viral infections showed a similar association with MS risk

Together, these findings strongly supported the conclusion that EBV infection precedes and likely contributes to MS development.

Stanford Medicine study: EBV and brain proteins share similarities

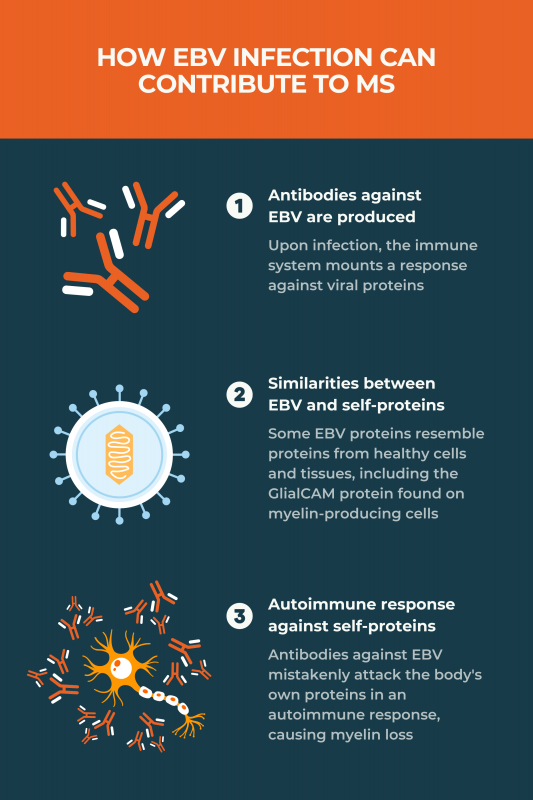

Soon after the Harvard MS study was published, researchers at Stanford Medicine identified a possible biological mechanism explaining the link between EBV infection and MS.

MS is characterized by immune attacks against the myelin sheath, a protective substance that surrounds nerve fibers. Myelin is produced by cells called oligodendrocytes in the brain and spinal cord.

The Stanford team showed that:

- an EBV protein called EBNA1 is structurally similar to GlialCAM, a protein produced by oligodendrocytes

- antibodies made by MS patients against EBNA1 also bound to GlialCAM due to this resemblance

This cross-reactivity suggests that EBV might be driving the attacks against myelin through a mechanism known as molecular mimicry.

Put simply, when a person is infected with EBV, they will make antibodies against EBV proteins, including EBNA1, in an attempt to suppress the virus. However, these antibodies will also target the GlialCAM protein, driving the aberrant immune attacks that cause myelin sheath damage in MS.

More recent research on EBV and MS

Since these landmark studies, researchers have focused on further understanding the mechanisms linking EBV and MS.

Newer studies have identified additional nervous system proteins beyond GlialCAM that could be the target of molecular mimicry. Some have also identified immune-related mechanisms beyond molecular mimicry that may be involved in driving MS in individuals infected with EBV.

Despite increasing evidence that EBV causes MS, the virus alone is not enough to trigger disease. Instead, EBV appears to interact with other genetic and environmental MS risk factors.

How do you become infected with EBV?

EBV spreads through contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person, especially saliva, but also through blood and semen. Common routes of transmission include:

- kissing

- sharing food, drink, utensils, or toothbrushes

- touching items that children have drooled on

- sexual contact

- medical procedures, such as blood transfusions or organ transplants

When infected with EBV, a person may remain contagious for weeks, even if they exhibit no overt symptoms of the virus. People may also spread the virus if it reactivates, no matter how much time has passed since the first infection.

Tests used to detect EBV infection

When it comes into contact with a virus or other harmful invader, the immune system generates antibodies that persist in the body even after the infection is resolved. For this reason, blood tests to detect antibodies against EBV proteins are the most effective way to determine if a person has ever been infected.

Because specific antibodies emerge at different points after an EBV infection, test results can help determine whether a person was infected recently or in the past. These tests are commonly used in research studies examining the link between EBV and MS.

Can you prevent EBV infection?

There is currently no vaccine to prevent EBV infection. Until one becomes available, the best ways to protect against infection are to reduce contact with an infected person. Some practical steps can include:

- avoiding kissing when someone is ill

- not sharing food, drinks, or personal items

- practicing good hygiene

Investigational MS therapies targeting EBV

As evidence linking EBV to MS continues to grow, there has been an increased focus on developing therapies that might reduce disease activity by targeting EBV.

Therapeutic vaccines and immunotherapies

Scientists are developing therapeutic EBV-targeted vaccines and other immunotherapies that are generally intended to retrain the immune system to better control EBV.

One example is a therapeutic vaccine from Moderna called mRNA-1195, which is designed to prevent the reactivation of latent EBV infection. The vaccine is currently being tested in a Phase 2 study (NCT06735248) in people with relapsing forms of MS.

Another area of interest is T-cell therapy for MS, which involves using immune T-cells to target and eliminate EBV-infected cells.

Antiviral treatments

Researchers are also investigating whether antiviral drugs can suppress EBV activity and improve MS outcomes. Ongoing trials include:

- STOP-MS (ACTRN12623000849695), a Phase 3 trial testing whether spironolactone or famciclovir can slow the progression of disability in people with progressive forms of MS.

- FIRMS-EBV (ACTRN12624000423516), a Phase 3 study evaluating whether spironolactone or tenofovir alafenamide can ease fatigue in people with relapsing-remitting MS.

- A Phase 2 trial (NCT05957913) examining whether the antiviral Truvada (tenofovir/emtricitabine) has antiviral activity against EBV and reduces fatigue in people with MS.

Vaccines to prevent EBV infection

Because an EBV infection is necessary for MS to develop, preventing EBV infection altogether is considered a promising long-term strategy for reducing MS risk. Several preventive EBV vaccines are in early development, including:

- Moderna’s mRNA-1189, which is being assessed in healthy young adults in a Phase 1 trial (NCT05164094)

- a vaccine called gp350-Ferritin, which was developed by the National Institutes of Health and is being tested in healthy young adults in a Phase 1 trial (NCT04645147)

- Merck’s EBV vaccine, called V350A and V350B, which is in Phase 1 testing (NCT06655324) in healthy adults

What other diseases are associated with EBV?

EBV has been linked to several other autoimmune conditions, including:

- systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- rheumatoid arthritis

- Sjögren’s disease

- celiac disease

- type 1 diabetes

- inflammatory bowel disease

- juvenile idiopathic arthritis

The virus also is closely associated with certain types of cancer, such as:

- lymphomas, including Hodgkin’s and Burkitt lymphomas

- nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- stomach cancer

Is there a link between MS and any other viruses?

Over the years, studies have linked MS to several viruses, but none have shown a link as strong as EBV, and evidence remains limited for most viruses.

Two families of viruses appear to have the most plausible evidence linking them to MS:

- Herpesvirus: A number of studies have found that infection with the human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), another virus in the herpesvirus family to which EBV also belongs, may be associated with a greater MS risk and with more active or severe disease in MS patients. HHV-6 may further increase MS risk in people with high EBV antibody levels.

- Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs): These are elements of ancient viral DNA that were incorporated into the human genome and can be reactivated in certain circumstances. Accumulating evidence suggests that certain HERVs may contribute to autoimmunity in MS, and that EBV can activate HERVs.

Multiple Sclerosis News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by