Signaling Protein of Intestines May Trigger Nervous System Inflammation in MS, Study Says

Written by |

A signaling protein (Smad7) that usually blocks the activity of a molecule called transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) appears to be overactive in people with multiple sclerosis (MS), leading to the activation and migration of immune cells from the intestine to the central nervous system, a study reports.

The study, “Smad7 in intestinal CD4+ T cells determines autoimmunity in a spontaneous model of multiple sclerosis,” was published in the journal PNAS.

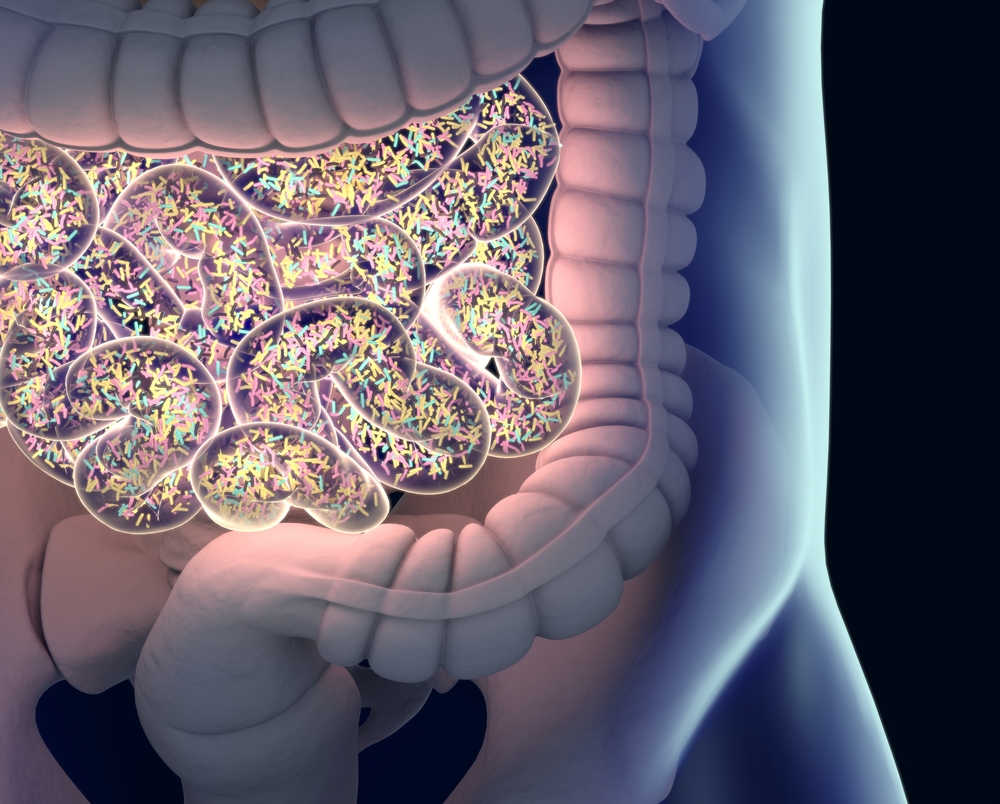

Although the mechanisms that trigger MS are still poorly understood, it is thought that certain environmental factors that compromise the intestinal barrier — the barrier that separates the intestines from the rest of the body — may factor in many autoimmune diseases, including MS.

More specifically, it is thought that the activation of immune T-cells at barrier organs such as the skin, lungs, and intestines, may be directly implicated in these disorders. (Activated cells are cells, including immune cells, that change in response to a stimulus.)

The Smad7/TGF-beta signaling pathway is one of the chemical cascades that controls the differentiation of immune T-cells, the main players in inflammation in autoimmune disorders.

Previous studies have shown that in patients with Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), Smad7 is produced in excess in the intestines, compromising the intestinal barrier and increasing tissue inflammation and disease activity.

Now, researchers at Ruhr-University Bochum in Germany and collaborators set out to investigate if the Smad7/TGF-beta signaling cascade in the intestines could also play a role in MS onset.

They began with a series of experiments in a mouse model of opticospinal encephalomyelitis (OSE), a condition that mimics MS in humans.

The team worked with animals with three different types of intestinal T-cells: some that had been genetically modified to produce large amounts of Smad7, others genetically modified to be unable to produce any Smad7, and others that produced Smad7 in normal amounts.

After comparing the three types of animals, researchers found that those whose T-cells produced the largest amounts of Smad7 had the most severe disease symptoms and faster progression. They also discovered that T-cells in their intestines were more active, and tended to migrate and invade their central nervous system, causing inflammation.

In these animals, the balance between regulatory T-cells and killer T-cells, which is normally control by the Smad7/TGF-beta signaling cascade, was also found to be completely disrupted. (Regulatory T-cells are immune cells that control the activity of other immune cells, while killer T-cells work to destroy anything the immune system sees as a threat.)

In contrast, in animals whose intestinal T-cells were unable to produce Smad7, no clinical signs of disease were found.

Investigators then decided to analyze and compare intestinal biopsies taken from 27 MS patients with those of 27 healthy individuals serving as controls, to see if a similar trend existed.

Findings confirmed that in MS patients, the activity of TGF-beta was lower than normal, while Smad7 was unusually active.

“A dysregulation of TGF-beta/Smad7 signaling was also found in intestinal biopsies from MS patients, indicating a contribution of the intestinal barrier in the immunopathology of MS,” the researchers wrote.

As in the animals, in MS patients a shift was also seen in the balance of regulatory and inflammatory T-cells that favored the expansion of inflammatory T-cells.

“For other autoimmune diseases such as Crohn’s and other inflammatory bowel diseases, researchers are already aware that Smad7 offers a promising therapeutic target; our results suggest that the same is true for multiple sclerosis,” Ingo Kleiter, a professor and neurologist at Marianne-Strauß-Klinik in Berg (formerly at the Bochum university hospital), and a corresponding study author, said in a press release.

“Researchers are increasingly exploring intestinal involvement in the development and progression of MS,” added Simon Faissner, a professor and neurologist at Marianne-Strauß-Klinik in Berg and co-author of the study.