Remyelination Candidate Opicinumab Failed in Phase 2 Trial in MS, But Biogen Won’t Give Up

Written by |

Although a Phase 2b trial of the remyelination drug candidate opicinumab (also known as anti-LINGO-1 and BIIB033) failed to meet its primary goal of improving disability in relapsing and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS), researchers believe the drug did cause “fairly strong” improvements.

The trial evaluated four doses of the treatment. Analyses indicated the two intermediate doses made patients better, while the highest and the lowest doses had no detectable effects.

Dr. Peter A. Calabresi, director of the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis Center, presented insights from the trial at the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) 2017 Annual Meeting, held April 22-28 in Boston. The study, “Efficacy Results from the Phase 2b SYNERGY Study: Treatment of Disabling Multiple Sclerosis with the Anti-LINGO-1 Monoclonal Antibody Opicinumab,” was part of a session on progressive MS therapeutics.

In the trial (NCT01864148) — called SYNERGY by opicinumab’s developer, Biogen — 418 participants were randomized to receive one of four opicinumab doses in combination with Avonex (interferon beta-1a), or placebo with Avonex; 334 of the 418 completed the study.

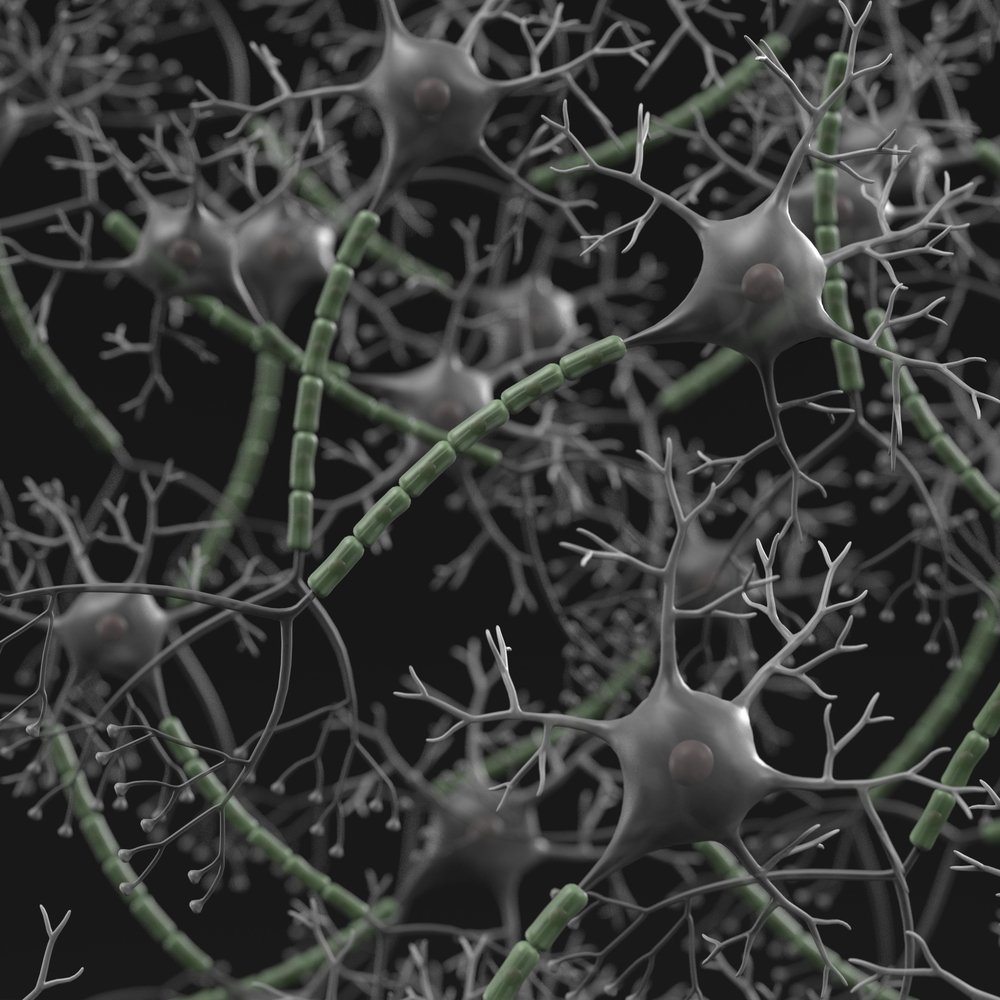

Opicinumab is believed to trigger remyelination by preventing the actions of LINGO-1 — a factor that suppresses myelination and axonal regeneration. In the trial, researchers measured the percentage of patients who improved during three months or more in the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), the 25-Foot Walk, the 9-Hole Peg Test and the 3-Second Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test.

At the beginning, participants were mildly to moderately disabled, with EDSS scores of 2 to 6.

According to the researchers, placebo-treated participants improved by 51.6 percent. Those in the highest-dose and lowest-dose groups saw estimated improvements of 51.1 and 41.2 percent, while patients receiving the intermediate doses seemed to benefit most from the treatment.

Those taking 10 mg of opicinumab per kilogram of body weight improved by 65.6 percent, while for the 30 mg/kg group, scores improved by 68.8 percent.

“The take-home message is that the very lowest and highest doses don’t appear to do anything, but that we saw a fairly strong signal in the intermediate doses,” Calabresi, an associate professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, said in an AAN update in Neurology Today.

Analyses also showed that the treatment was more effective in younger people and those with a shorter disease duration. Also, relapsing patients benefitted more than secondary progressive patients — findings that are often seen in trials investigating new MS treatments.

Researchers also found two imaging methods that, in combination with disease duration, could be used to predict the likelihood of response.

Not everyone, however, agreed on the design of the trial. Dr. Timothy L. Vollmer, vice-chair of clinical research at the University of Colorado, Denver School of Medicine, questioned the choice of interferon as the comparator drug.

“They specifically excluded patients on highly effective therapies like Tysabri [natalizumab] or Gilenya [fingolimod],” said Vollmer, who was not involved in the trial. “If you’re trying to induce remyelination with an add-on agent and you don’t shut off the inflammatory process in the brain first, it’s hard to see an effect.”

Although Calabresi agreed with Vollmer’s argument, he said the current understanding of remyelination states that a certain level of inflammation is necessary to enable repair. “There’s still some debate, and we’re still learning,” Calabresi said. “In a future study, it is likely there will be cohorts on natalizumab and other therapies with more effective inflammation suppression.”

The study’s failure to meet its primary goal is by no means the end of the road for opicinumab, he added: “The plan is to move forward with the middle dose that looks best, 10 mg, and to recruit for patients most likely to be responders. This will be a bit of personalized medicine.”