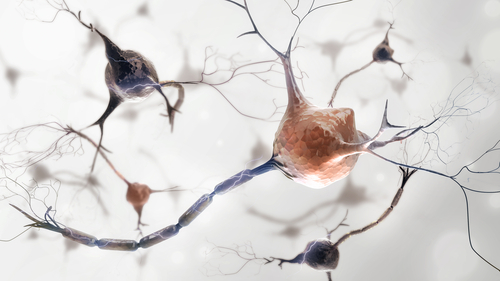

Microglia Cells Diverse with Distinct Subtypes and Certain Ones May Contribute to Inflammation, Study Finds

Microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, were seen to change throughout the lifespan of mice in a study — and to be diverse, with distinct cell subtypes. Those with pro-inflammatory behavior may be disease-causing, as they were found to accumulate in the brains of a mouse model of multiple sclerosis and brain tissue from MS patients.

These results open new possibilities for targeted treatments to enhance microglia’s protective properties, and to block microglia cells that promote MS and other diseases.

The study, “Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Microglia throughout the Mouse Lifespan and in the Injured Brain Reveals Complex Cell-State Changes” was published in the journal Immunity.

Microglia comprises 10 percent of all brain cells, and are known to respond rapidly to changes in their environment. They are one of the dominant cell types found in MS lesions, and their presence is associated with damage to nerve fibers (axons) and the loss of the protective myelin sheath (a hallmark of MS).

However, whether all microglia cells are the same or whether they are heterogeneous, i.e., they exist as sub-populations, remained unknown.

“Up until now, we didn’t have a good way of classifying microglia. We could only say how branched they look, how dense they look under a microscope,” Timothy Hammond, the study’s first author and a research fellow in neurology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, said in a press release.

“We wanted to get an idea of what microglia were doing and ‘thinking,’” he added.

Hammond and colleagues at Harvard investigated the potential heterogeneity within microglia cells of mice. For that, they analyzed the RNA content — RNA is the chemical cousin of DNA — of individual microglia cells in the mouse brain throughout the animals’ lifespan (starting before birth and through to death), as well after acute brain injury.

Connect with other patients and caregivers, find support and share tips for living well with MS in our MS News Today online forums.

In total, the team analyzed more than 76,000 individual microglia using a technique called Drop-seq, developed in the lab of Steven McCarroll, PhD, at the Blavatnik Institute at the Harvard school, which allows them to see which genes are on or off.

Researchers looked at single cells’ RNA profiling, and by comparing profiles among the different cells identified nine subgroups of microglia, which expressed unique sets of genes. Some groups of cells were almost exclusively present during the embryonic or newborn stages of life, while others appeared only after brain injury.

These results showed that microglia are heterogeneous, or diverse, and that the different cell groups may contribute differently to diseases like MS.

“The signatures also tell us something about what these cells are doing,” Hammond said. “If we see microglia in disease, for example, we can begin to parse out: Are they contributing to the disease or are they trying to repair the brain? We think this will help uncover new and interesting roles for microglia.”

Next, the researchers overlapped the different microglia subgroups with a map of the brain to see where the cells were located.

Results showed the cells were located in different regions of the brain – for example, cells in group 4 clustered near the brain’s developing white matter, where nerve cells coated with myelin are located and is the prime target for immune system attacks in MS.

This finding suggests that this microglia subgroup could be involved in myelination of nerve fibers.

“We don’t see those microglia at any other time point or area of the brain,” Hammond said. “We think they could be important to how the white matter develops and how axons connect to different parts of the brain.”

Researchers then used a mouse model of MS, and detected the activation of a specific subgroup of pro-inflammatory microglia cells — group number 8. This subtype was also found in brain tissue samples from MS patients.

“These microglia are very inflammatory compared with normal microglia,” Hammond said. “It could be a pathological subset that we normally wouldn’t see, but because we sequenced so many microglia we were able to detect this small population.”

Microglia cell diversity was greater in mice at young ages, but persisted throughout the animals’ lifespan and even increased, in the case of pro-inflammatory cells, in the aged brain and diseased brains.

“These distinct microglia signatures can be used to better understand microglia function and to identify and manipulate specific subpopulations in health and disease,” the researchers wrote.

Specifically, if researchers can identify and assess the contribution of each cluster of microglia cells to diseases like MS, they might be able to design tailored treatment approaches that block the “bad” microglia cells that contribute to MS development, and promote those with protective properties that may help halt the disease.

“Tim’s work has broad implications for the development of new microglia biomarkers and tools that can be used to track, identify and manipulate specific subpopulations, in both health and disease,” said Beth Stevens, an associate professor of neurology at Boston Children’s and the study’s co-lead author.