New PET Scan Radiotracer May Help Identify Early Signs of MS Progression, Study Reports

Written by |

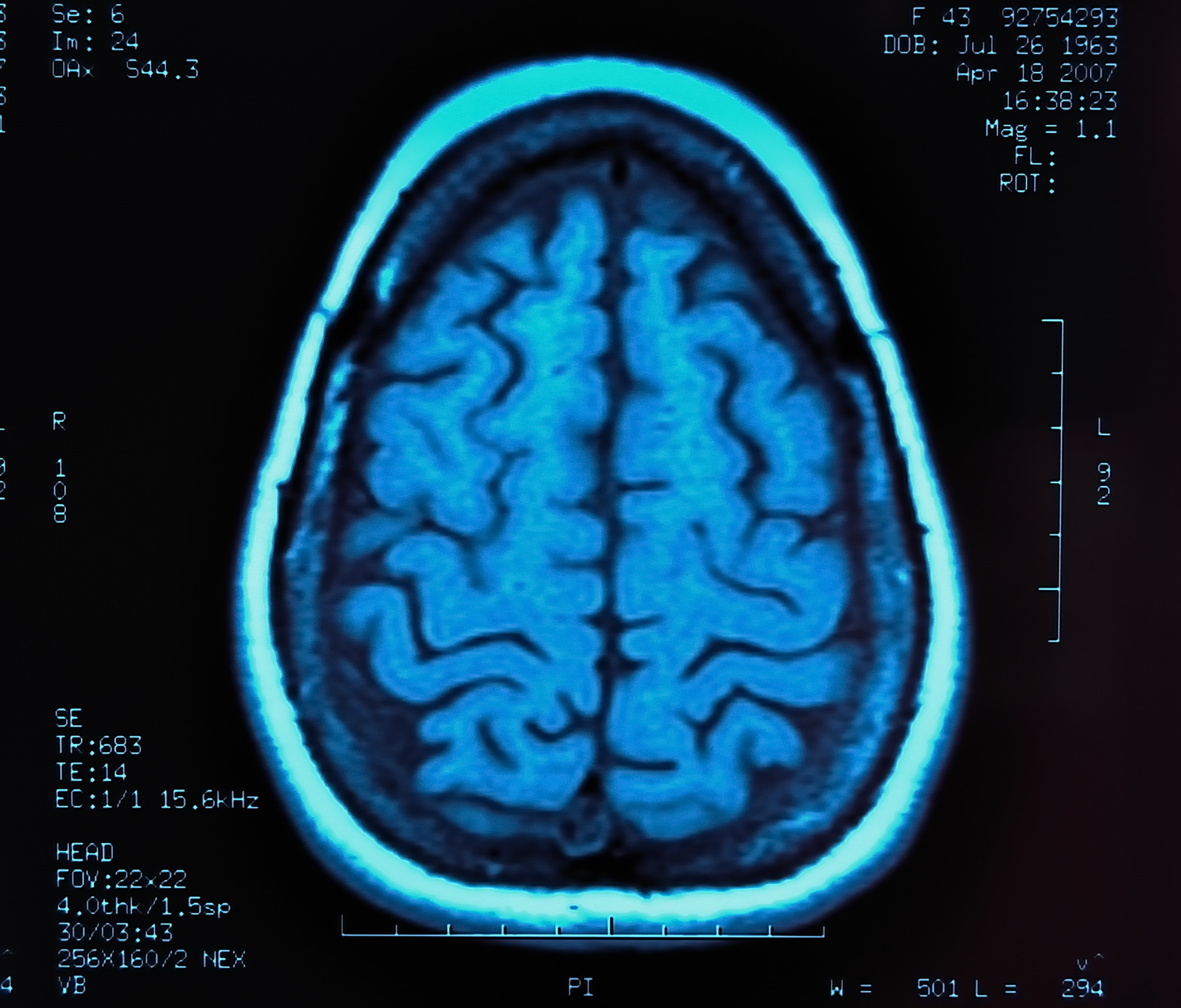

A new radiotracer called [F-18]PBR06, used in positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, helps detect changes in the brain’s grey matter that are linked to progressive forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), a study shows.

The findings support [F-18]PBR06’s potential for detecting signs of disease progression even before patients show visible symptoms.

“Unless we can measure the progress of a disease accurately, our ability to treat that disease remains limited,” Tarun Singhal, a neurologist at the Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and the study’s lead author, said in a press release.

“When a patient tells us that their symptoms are worsening, we want to have a technology that can reflect that, or better yet, predict the progression before it is clinically obvious. This technique may have the potential to do that and give us critical insights into neurodegeneration and its relationship with neuroinflammation,” Singhal added.

The study, “Gray matter microglial activation in relapsing vs progressive MS: A [F-18]PBR06-PET study,” was published in the journal Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation.

The central nervous system has two types of tissue: grey and white matter. MS is typically considered a disease of the brain’s signal-conducting white matter, where myelin — the protective coat of neurons, damaged in MS — is most abundant.

Want to learn more about the latest research in MS? Ask your questions in our research forum.

However, disability progression in MS is linked with alterations in grey matter, specifically the activation of microglia — the central nervous system’s immune cells — and neuronal loss. Lesions in white matter often remain unchanged as the disease progresses, as shown by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

“There’s more to multiple sclerosis than white matter lesions,” said Singhal. “There’s evidence of inflammation in the brain’s grey matter, not just the white matter.”

In a Phase 1/2 study (NCT02649985), researchers determined whether a new molecule tracer, called [F-18]PBR06, could be used to measure activation of microglia in the grey matter of people with MS using PET.

PET is an imaging technique that measures tissues’ metabolism using small amounts of radioactive materials, called radiotracers, along with a special camera and computer. This helps evaluate organ and tissue function.

[F-18]PBR06 targets a protein, called 18-kDa-translocator protein (TSPO), that is found in microglia and immune cells called macrophages. TSPO is a marker of inflammation.

Compared with other radiotracers, like the C-11 radioisotope, [F-18]PBR06 has a much longer half-life — 110 minutes versus the 20 minutes of C-11. This allows for better detection, improved image quality, and better discrimination of a real signal.

The study included 12 patients with MS — seven with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and five with secondary progressive MS (SPMS) — and five healthy people as controls.

Results showed that, compared with the brains of healthy controls, activation of microglia in grey matter was higher in the MS patients. This was shown by a increased uptake of [F-18]PBR06. The activation was seen in the so-called sub-cortical grey matter, including the hippocampus, parahippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and amygdala brain regions. These brain areas control processes like emotion, memory, and cognition, all commonly affected in MS.

Individuals with SPMS, in particular, had increased microglial activation in a region called the thalamus, compared with RRMS patients and healthy controls.

Microgial activation correlated with physical disability, as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale and timed 25-foot walk test scores. Moreover, microglial activation in the thalamus was linked with shrinkage (atrophy) of the brain, and disease progression.

“There is an urgent need to identify an imaging biomarker linked to progressive MS, and our results suggest that [F-18]PBR06 PET is a promising technique in this regard,” the researchers said.

“Here we have a technique to detect it [disease progression] and a path to develop this technique for use in the clinic in looking for early signs of progression and the effects of treatments,” Singhal concluded.