Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS)

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a neurological disorder characterized by immune-related damage to nerve cells, can be classified into several types based on how its symptoms develop and progress.

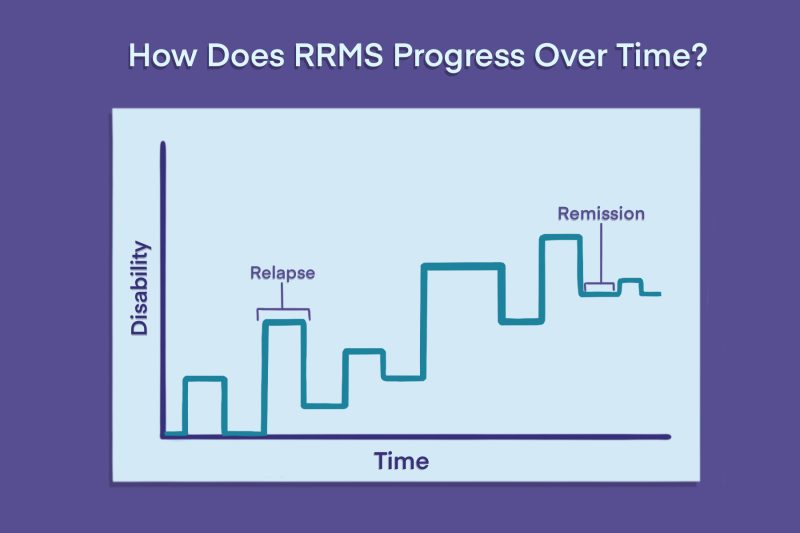

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) is a form of the disease characterized by periods of new or worsening symptoms, called relapses, interspersed with periods of remission in which symptoms ease and stabilize.

RRMS is the most common type of MS — accounting for around 85% of all newly diagnosed cases — although some people may later transition to a progressive form of the neurodegenerative disease.

What is relapsing-remitting MS?

In MS, the immune system launches mistaken inflammatory attacks that damage the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord.

Specifically, the CNS autoimmune disease involves attacks on myelin, a fatty substance that surrounds and protects nerve cells. The resulting inflammation and myelin loss, or demyelination, causes a variety of neurological symptoms.

In RRMS, a person cycles through periods where these symptoms emerge or get worse, followed by recovery periods where symptoms ease or disappear.

What is an MS relapse?

An MS relapse refers to a period when new symptoms appear, prior symptoms return, or existing ones get substantially worse. Relapses are also referred to as exacerbations, attacks, or flare-ups.

In RRMS, the inflammatory attacks on the CNS are not constant — they occur in waves. MS relapses happen when the immune system is actively targeting nerve cells.

To be officially considered a relapse, the exacerbation episode must:

- last at least 24 hours

- occur without a change in body temperature, infection, or other potential cause

- occur at least 30 days after the start of a previous relapse

How long does a relapse last?

Relapses are different for everyone, and can last anywhere from a few days to a few months. Typically, symptoms worsen quickly over a period of hours or days and last a few weeks.

Common relapse triggers

Not every relapse has an identifiable trigger. But sometimes, patients can identify factors that make a relapse more likely to happen or cause its symptoms to be worse. While this varies substantially between individuals, some commonly reported ones include:

Women commonly report having fewer relapses during pregnancy, but the risk of relapse generally increases in the months just after giving birth, or the postpartum period.

Certain factors, like heat and infection, can cause a temporary worsening of MS symptoms that feels a lot like a relapse. However, these episodes, called pseudoexacerbations, are not driven by underlying inflammatory activity in the CNS and are not considered a true relapse. They usually resolve within a day.

Remission vs. progression

When an episode of inflammatory disease activity ends, patients enter a period of recovery, called remission. During MS remission, symptoms may resolve completely or partially.

Damage that occurs during the relapse can mean that some symptoms may persist permanently; however, there is generally no apparent disease progression during remission, meaning that symptoms do not continuously worsen. This lack of apparent MS progression during the remission period differentiates RRMS from progressive forms of MS, where symptoms worsen over time, even without relapses.

Even in between relapses, MS can still be causing subtle damage that leads to slowly progressing disability even without an exacerbation or evidence of new disease activity. This is called progression independent of relapse activity, or PIRA, and may not cause obvious symptom changes.

RRMS is considered active if patients experience relapses and/or have evidence of new disease activity on MRI scans. If there is a sustained increase in disability after a relapse, a person’s RRMS is characterized as worsening.

Onset: Transitioning from CIS to RRMS

Sometimes, a single episode of MS-like symptoms doesn’t give doctors enough information to formally diagnose MS. If this is the case, an individual may instead get a diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome, or CIS.

For many people, CIS is considered a “first relapse.” If they go on to show new signs of disease activity — in the form of another relapse or evidence of new areas of damage (lesions) on MRI scans — it may be enough to warrant an RRMS diagnosis.

Based on 2024 updates to the McDonald criteria — a set of guidelines used to diagnose MS — some people previously diagnosed with CIS may now meet the criteria for an RRMS diagnosis right away without needing to show signs of further disease activity.

Some people with CIS never experience new disease activity beyond the initial attack and aren’t diagnosed with clinically definite MS.

Symptoms of RRMS

As in other MS types, RRMS symptoms depend on which parts of the nervous system are affected. Symptom severity during a relapse can also vary substantially.

While many of the symptoms overlap between relapsing and progressive forms of the disease, people with RRMS are less likely to experience problems with walking and mobility than those with progressive MS.

Common RRMS symptoms include:

- fatigue

- numbness and tingling or other unusual sensations

- vision problems

- spasticity

- bladder, bowel, or sexual problems

- cognitive impairment and emotional challenges

How long does RRMS last?

MS is a lifelong disease, and each person will experience a different disease course. Factors like treatment, demographics, lifestyle habits, and biology can influence this course.

Without treatment, about 90% of RRMS patients will progress to a more severe disease form called secondary progressive MS (SPMS) within 25 years, although the timing of the transition can vary. In SPMS, symptoms gradually worsen over time, regardless of relapse activity.

However, most patients today receive disease-modifying treatments that can drastically delay or prevent the onset of SPMS.

Now, more people with RRMS are going their entire lives without ever progressing to SPMS. For example, one large study found that 1 in 10 people with RRMS, most of whom had received at least one DMT, progressed to SPMS after a median of more than three decades.

There are no universally accepted criteria for diagnosing RRMS versus SPMS, so several tests and careful observation may be necessary to identify the progression.

Diagnosis of RRMS

There isn’t a single test for diagnosing RRMS. Instead, the diagnostic process typically involves:

- careful review of a person’s medical history

- physical and neurological exam, to identify typical MS symptoms

- MRI scans, to look for MS-related lesions in the brain and spinal cord

- a lumbar puncture, to analyze the spinal fluid for signs of MS-related inflammation

Together, these evaluations are used to identify patterns of inflammation and nerve damage consistent with MS and rule out other conditions that may cause similar symptoms.

The McDonald criteria outline the combinations of findings that would warrant an MS diagnosis, with MRI lesions being key to all of them. For example, if lesions are found in at least four of the five CNS regions commonly affected in MS, that alone is sufficient to diagnose the disease, even without a clinical relapse. If fewer areas of damage are observed, other types of evidence may be needed to support the diagnosis.

The most recent criteria use a unified framework for both relapsing and progressive MS types. A physician will specifically diagnose RRMS based on the pattern of symptoms and progression.

Women are up to three times more likely to be diagnosed with MS than men, and RRMS is also more common among women. Symptoms of RRMS typically begin to appear when patients are in their 20s and 30s — often earlier than in progressive types of MS.

Treatment of RRMS

There is no cure for RRMS. Treatment typically involves disease-modifying therapies for MS, or DMTs, which have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of relapse and slow the rate of disease progression. DMTs approved in the U.S. to treat RRMS include:

- Aubagio (teriflunomide)

- Avonex (interferon beta-1a)

- Bafiertam (monomethyl fumarate)

- Betaseron (interferon beta-1b)

- Briumvi (ublituximab-xiiy)

- Copaxone (glatiramer acetate injection)

- Extavia (interferon beta-1b)

- Gilenya (fingolimod)

- Kesimpta (ofatumumab)

- Lemtrada (alemtuzumab)

- Mavenclad (cladribine)

- Mayzent (siponimod)

- mitoxantrone

- Ocrevus (ocrelizumab)

- Ocrevus Zunovo (ocrelizumab and hyaluronidase-ocsq)

- Plegridy (peginterferon beta-1a)

- Ponvory (ponesimod)

- Rebif (interferon beta-1a)

- Tascenso ODT (fingolimod)

- Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate)

- Tyruko (natalizumab-sztn)

- Tysabri (natalizumab)

- Vumerity (diroximel fumarate)

- Zeposia (ozanimod)

If a severe relapse occurs, inflammation-suppressing therapies may be used to more quickly ease symptoms. Relapse management may include glucocorticoids, or corticosteroids for MS relapse, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-based therapies, or plasmapheresis.

Various types of supportive care, including medications, rehabilitation, and lifestyle changes, can help with symptom management in RRMS. For example, lifestyle changes can help alleviate MS fatigue, while certain medications may be beneficial for individuals experiencing MS-related vision changes.

Outlook of RRMS

The prognosis of RRMS varies markedly from person to person. Among other factors, it depends on the number of relapses a person experiences and their degree of recovery during remission. Generally, more frequent relapses with poorer recovery lead to a faster accumulation of disabling symptoms in people living with RRMS.

After receiving an RRMS diagnosis, patients should talk to their healthcare team about developing a comprehensive care plan. An individually tailored treatment strategy can help slow disease progression, ease symptoms, and delay conversion to SPMS.

In addition to medication, a therapeutic plan may involve lifestyle adjustments, such as quitting smoking, adopting a healthy diet, and participating in physical or occupational therapy to enhance daily functioning.

Multiple Sclerosis News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by