MS Researchers Watch as Myelin-producing Cells Migrate and Mature

Written by |

Researchers have described the mechanisms by which cell precursors of oligodendrocytes — the cells responsible for the generation of myelin in the central nervous system — migrate from their birthplace to their workplace during brain and spinal cord development, and begin to mature and wrap about nerve fibers. The finding, the authors said, may have the potential to aid migration and maturation, and so “significantly reduce” the severity of relapses in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients.

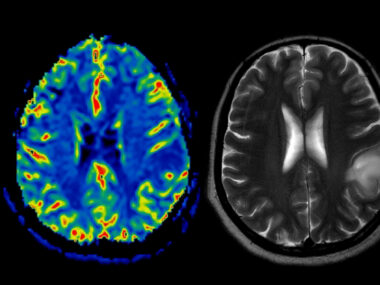

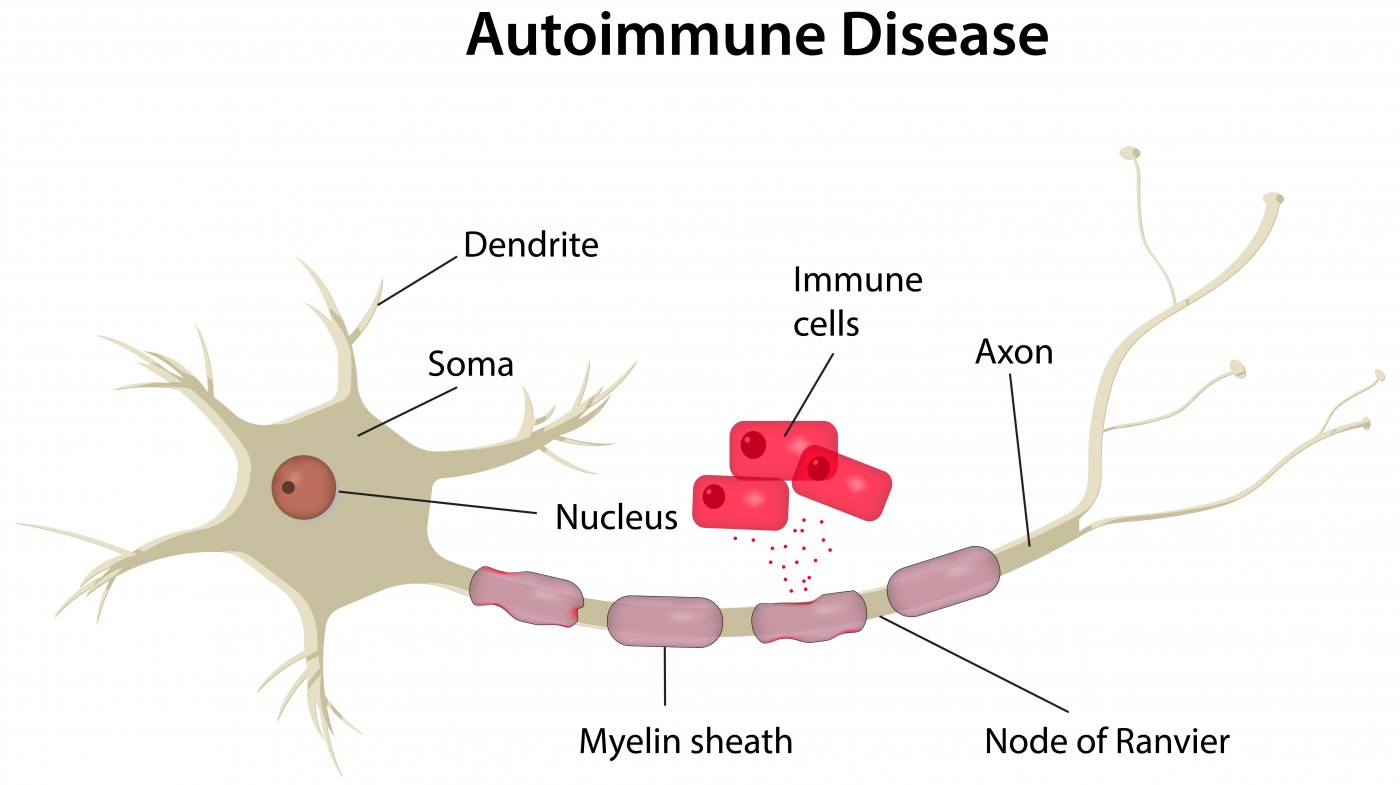

Myelin is a lipidic material that protects nerve fibers in the central and peripheral nervous system. Myelination, the formation of the myelin protection in neurons, is carried out by oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system (CNS). Understating the formation of oligodendrocyte cells is of considerable importance, as MS development is deeply connected to damage done to the protective myelin sheaths during immune system attacks, eventually leading to neuron death.

The research article, “Oligodendrocyte precursors migrate along vasculature in the developing nervous system,” was published in the journal Science.

Oligodendrocytes develop from oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) that first, as other precursor cells during brain development, migrate extensively. However, the mechanism of migration, including the substrate that allows them to migrate, has long remained elusive.

While studying how OPCs differentiate into a mature form, the researchers discovered that the cells use the vasculature as a physical substrate for migration. Previous research has shown that the Wnt signaling pathway inhibits the transformation of immature cells into mature cells, until they are in the correct place to form myelin.

While studying how OPCs differentiate into a mature form, the researchers discovered that the cells use the vasculature as a physical substrate for migration. Previous research has shown that the Wnt signaling pathway inhibits the transformation of immature cells into mature cells, until they are in the correct place to form myelin.

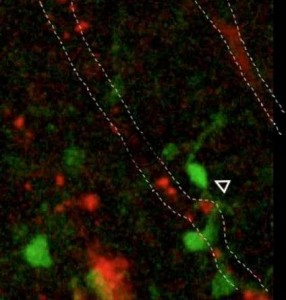

The researchers induced constant high levels of Wnt in mice, and observed that the OPCs couldn’t migrate properly and appeared to become stuck to blood vessels. This was confirmed by live imaging of migrating OPCs in the developing brains of untreated mice and also in human brain tissue, where researchers observed the migrating OPCs crawling along the blood vessels and “jumping” from one blood vessel to the other.

They also demonstrated that if the Wnt signaling pathway was blocked, the precursor cells fall off the brain vasculature, suggesting that Wnt signaling works to keep the cells associated with vessels during migration.

“It seems like Wnt signalling plays a dual role to coordinate the timing of migration and differentiation,” the study’s lead author, Dr. Stephen Fancy, assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology in UC San Francisco School of Medicine, said in a press release. “First it holds them in their immature form as they travel along the blood vessels, and then when they reach their destination it turns itself off to let them off their climbing frame and begin maturing.”

The researchers theorize that finding a way to conduct oligodendrocytes to the location of myelin damage observed in MS has the potential to reduce the severity and frequency of relapses suffered by MS patients.

“There are a number of drugs now that can help reduce the initial demyelination in MS, but there is currently no therapy to aid remyelination,” Dr. Fancy said. “This is one of those cases where by making discoveries about brain development, we stand to learn a lot about disease as well.”