Antibody Created in Lab Treats MS in Mice by Preventing Immune Cells from Piercing Blood-Brain Barrier

Written by |

Building on work began in stroke studies and applying it to multiple sclerosis, researchers in France report that an antibody they developed kept the blood-brain barrier intact in cellular and mice MS models despite the presence of inflammation, preventing immune cells from entering the brain.

The key to understanding the study by these INSERM investigators is the blood-brain barrier, and how an antibody that protects it presents a new approach to treating MS. The study, “Neuroendothelial NMDA receptors as therapeutic targets in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,” was published in the journal Brain.

While it might be natural to envision the blood-brain barrier as a lid, sealing off the brain from the rest of the body, it is actually composed of special layers of cells that line blood vessels in the brain and spinal cord. In other words, it’s a cellular barrier that forms tight connections between neighboring cells inside blood vessels, effectively preventing anything but fat-soluble molecules (which can travel across the cell itself) from leaking into the brain. If something else were to sneak through, another team of cells line the outside of the vessels and protect the brain from harmful substances.

In MS, like in other inflammatory brain conditions, immune cells travel to brain blood vessels, and are allowed to enter the brain through a loosening of blood-brain barrier structures. While it is not entirely clear how this loosening occurs, earlier research showed that the immune cells produce cascades of inflammatory signaling molecules that can make these normally closed structures open up.

A couple of years back, when the research team from Inserm Unit U919 studied stroke, the NMDA receptor caught their attention. They noted that when the receptor interacted with another molecule, called tPA, the blood-brain barrier would open. Their finding was supported by plenty of other studies, indicating that tPA is likely involved in MS and other inflammatory conditions in the brain.

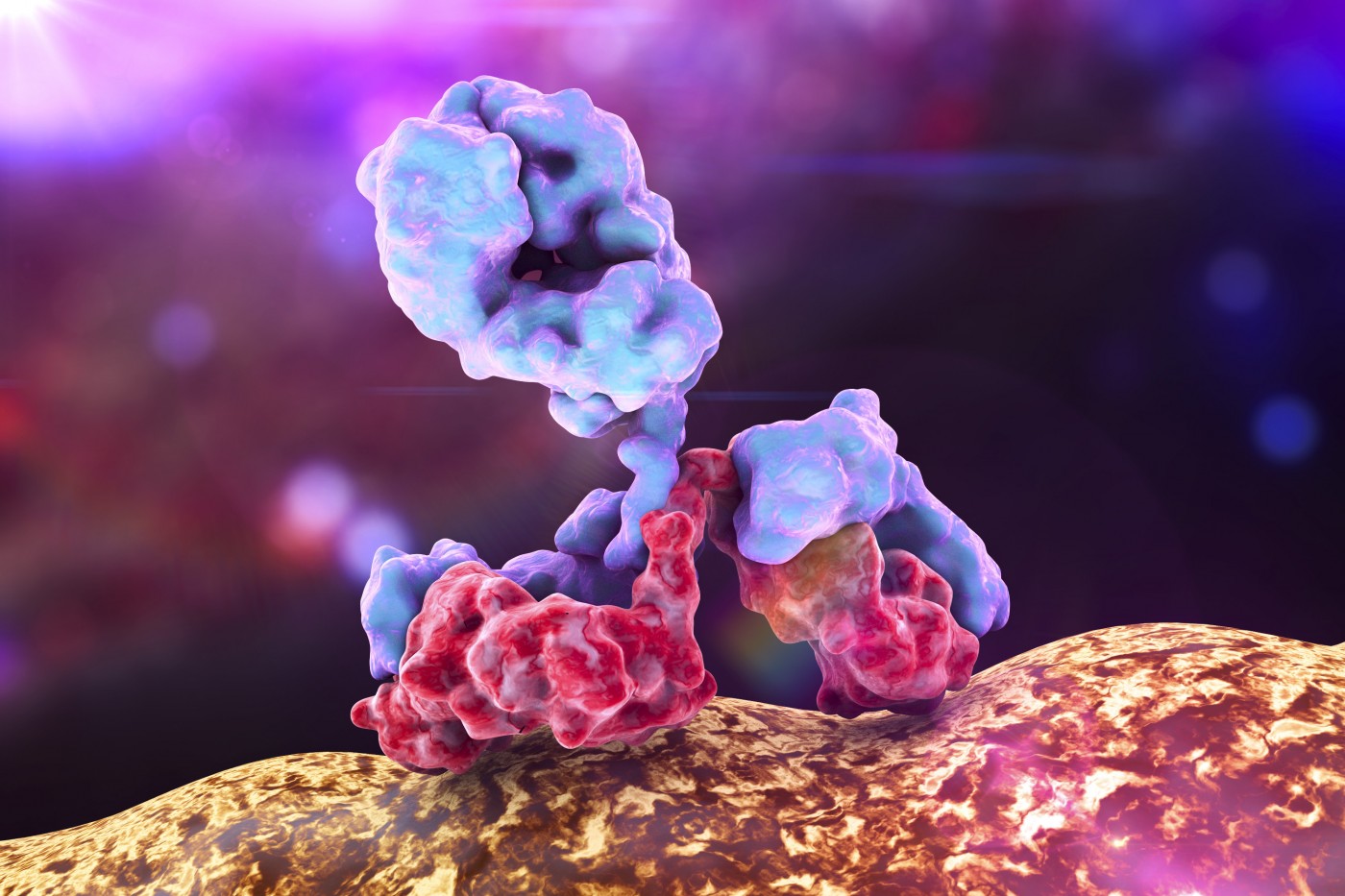

Taking this knowledge, the team developed an antibody, which they named Glunomab, that would bind to the NMDA receptor in a way that prevented it from interacting with tPA but left its other capabilities unaltered. This is a major strength of a proposed treatment targeting the NMDA receptor, as the receptor has numerous of other functions in the brain that, if disrupted, could cause severe side effects.

The researchers first tested the antibody in models of blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers in lab dishes. When mimicking inflammatory conditions, normally making the barrier loosen up, the antibody kept the barrier intact.

But cells in a dish do not necessarily reflect what is happening in a living being, so researchers put the antibody to test in a mouse model of MS. As they had hoped, Glunomab halted the progression of neurological deterioration in the form of motor symptoms. The mice also had fewer immune cells in the brain and spinal cord, and less demyelination.

The antibody was, however, completely ineffective when researchers performed the same test in mice engineered to lack tPA, proving that the effect really involved the interaction between these two brain factors.