Study Detailing New Way T-cells Attack Myelin May Explain Why Some MS Therapies Fail

Written by |

In a new and possibly important insight into the workings of the immune system, researchers discovered what it takes for T-cells to start targeting myelin sheets in multiple sclerosis (MS). The findings may also explain why some drugs fail to prevent autoimmunity in MS.

The study, “Trans-presentation of IL-6 by dendritic cells is required for the priming of pathogenic TH17 cells,” recently appeared in the journal Nature Immunology.

In earlier studies, the research team at Technical University of Munich (TUM) in Germany showed that the immune mediator IL-6 was part of the machinery that instructed T-cells (of a type called Th17) to attack myelin.

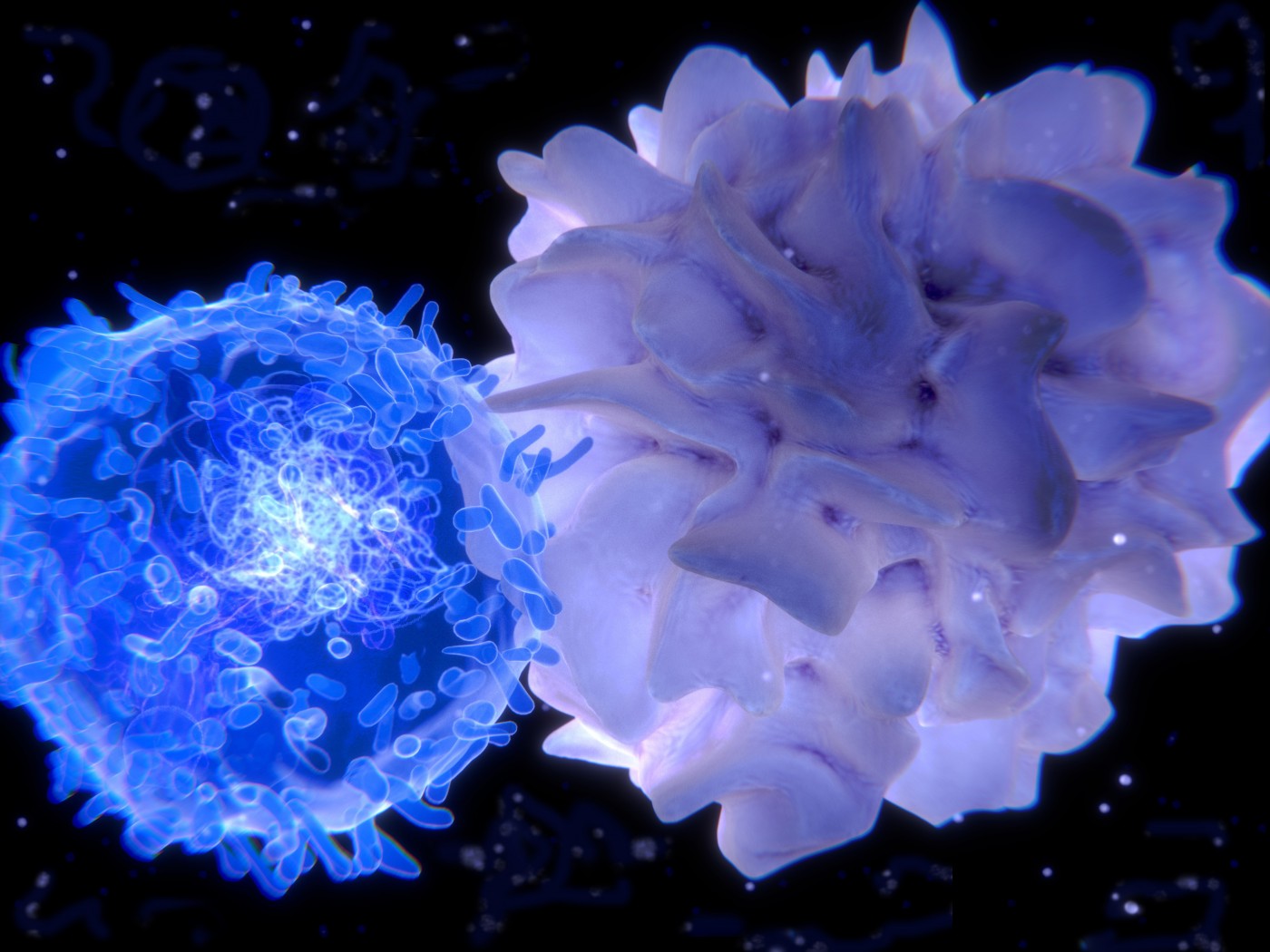

When T-cells are formed, they travel to lymph nodes throughout the body and wait for signals to act. Another immune cell — the dendritic cell — is crucial in telling the T-cells where their work is needed. This is done by presenting bits of the invader that the body wants to get rid of.

Most often, these are bits of bacteria or a virus. But in people with MS, dendritic cells wrongfully bring pieces of myelin to the T-cells. The TUM research team discovered that T-cells did not attack the myelin until an IL-6 signal was present.

While they learned in this earlier work that IL-6 is also secreted by dendritic cells, they also saw — surprisingly for the researchers — that IL-6 is sometimes not enough to get T-cells to launch an attack. It was clear that a piece of the puzzle was still missing.

In the new study, researchers discovered that while the very presence of the IL-6 signal is important, it is how that signal is presented that matters most.

Scientists already know that dendritic cells can use IL-6 for communication in two ways. A cell can release IL-6, which then diffuses into the liquid surrounding the cells until it hits a receptor on another cell. Or, cells can secrete both IL-6 and its receptor, which form a complex before docking to another cell.

The team discovered that, in the case of myelin-targeting T-cells, neither of these two methods were used. Rather, a third way exists for the use of IL-6 in cellular communication. Dendritic cells can place IL-6 like a flag on their surface, and come into direct contact with receptors on T-cells.

The researchers termed this new way “cluster signaling,” as dendritic cells and T-cells cluster together in the process. In contrast to the other ways of signaling, a T-cell receives the IL-6 signal at the same time as it receives other signals from dendritic cells. They believe that this concentrated timing creates a strong signal, making the T-cells more aggressive and efficient in their attacks on myelin.

Scientists have been trying to block IL-6 signaling to stop autoimmune processes. Such drugs are routinely used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, but in MS this type of therapy has not been successful.

“The results of our research can clarify why some therapies are successful and why others are not,” Thomas Korn, a professor of Experimental Neuroimmunology and the study’s senior investigator, said in a news release.

“The various drugs often block only one signaling method. If transmission through dissolved IL-6 is prevented, cluster signaling may still be possible,” said Ari Waisman, the head of the Institute for Molecular Medicine at the University Medical Center in Mainz, Germany, who collaborated with the TUM team on the study.