Dark Rimmed Brain Lesions May Be Signal of Aggressive Disease, NIH Study Says

Written by |

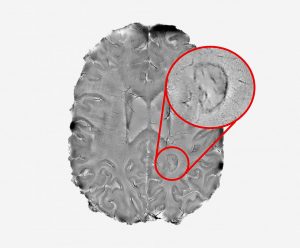

Dark rimmed spots on brain scans using a 7-tesla MRI may be a hallmark of more disabling MS forms. (Photo courtesy of Reich lab, NIH/NINDS)

Brain lesions appearing as dark rimmed, “smoldering” spots on imaging scans, representing active inflammation, may be a hallmark of more aggressive and disabling forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) report.

Using a powerful MRI brain scanner and a 3D printer, the team visualized brain images from nearly 200 MS patients and found that these spots — identified as chronic active lesions — may be used to signal people at a higher risk of more aggressive and progressing forms of the disease.

The study “Association of Chronic Active Multiple Sclerosis Lesions With Disability In Vivo” was published in the journal JAMA Neurology.

Dark rimmed spots on brain scans using a 7-tesla MRI may be a hallmark of more disabling MS forms. (Photo courtesy of Reich lab, NIH/NINDS)

“We found that it is possible to use brain scans to detect which patients are highly susceptible to the more aggressive forms of multiple sclerosis. The more chronic active lesions a patient has, the greater the chances they will experience this type of MS,” Daniel S. Reich, MD, PhD, the study’s senior author and a senior investigator at the NIH, said a news release.

“We hope these results will help test the effectiveness of new therapies for this form of MS, and reduce the suffering patients experience,” Reich added.

Previously, chronic active lesions could only be detected through an autopsy. But Reich and his team in earlier work showed that examining a living person’s brain using a highly powerful 7-tesla MRI scanner could accurately capture these lesions by their darkened, outer rims.

“Figuring out how to spot chronic active lesions was a big step, and we could not have done it without the high-powered MRI scanner provided by the NIH. It allowed us to then explore how MS lesions evolved and whether they played a role in progressive MS,” said Martina Absinta, MD, PhD, the study’s leader and a post-doctoral fellow in Reich’s lab.

The team scanned the brains of 192 MS patients taking part in a trial at the NIH’s Clinical Center. They found that 117 of them (56% of the initial studied population) had at least one rim lesion regardless of prior or ongoing treatment.

Further analysis showed that 84 patients (44%) had no rims, 66 (34%) had one to three rims, and 42 (22%) had four or more rimmed lesions.

Patients with four or more rimmed lesions went on to motor and cognitive disability at earlier ages, and were 1.6 times more likely to be diagnosed with progressive MS than those without rimmed lesions.

By analyzing certain parts of the brain, researchers also found that those with rimmed lesions had smaller brain volumes, less white matter, and smaller basal ganglia — structures lying deep inside the brain that are associated with a variety of functions, like voluntary motor movements, cognition, and emotion.

In a set of patients whose brains were scanned annually for at least 10 years, lesions lacking dark rims were found to shrink over time (reducing 3.6% a year), while rimmed lesions remained stable in size or grew (2.2% a year).

“Our results point the way towards using specialized brain scans to predict who is at risk of developing progressive MS,” Reich said.

The team also used a 3D printer to compare rimmed spots found on scans with lesions to those in samples taken from the brain of a progressive MS patient who died during the study.

Examining these samples under a microscope, scientists found that all growing rimmed spots previously detected on scans had the hallmark features of chronic active inflammation.

“Our results support the idea that chronic active lesions are very damaging to the brain,” Reich said. “We need to attack these lesions as early as possible.

“The fact that these lesions are present in patients who are receiving anti-inflammatory drugs that quiet the body’s immune system also suggests that the field of MS research may want to focus on new treatments that target the brain’s unique immune system — especially a type of brain cell called microglia,” he added. “At the NIH, we are actively seeking patients who want to participate in studies like these.”

Reich and his team have openly shared instructions for programming conventional MRI scanners found at most clinics to detect the rimmed chronic active lesions.

These studies were supported by NINDS’ Intramural Research Program, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation.