#ACTRIMS2021 – Reduced Methionine in Diet Eased Symptoms in MS Mice

Editor’s note: The Multiple Sclerosis News Today news team is providing in-depth and unparalleled coverage of the virtual ACTRIMS Forum 2021, Feb. 25–27. Go here to see the latest stories from the conference.

Reducing the essential amino acid methionine in the diet lessened multiple sclerosis (MS)-like symptoms in a mouse model of the disease, new research shows.

The findings suggest that a methionine-restricted diet, or treatments that target methionine-related biological processes, could be beneficial in MS.

The data were shared in the presentation, “Impact of Methionine Intake on Inflammation,” presented at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) Forum 2021 by Catherine Larochelle, MD, PhD, professor at the Université de Montréal in Canada.

Methionine is an essential amino acid. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, and being an “essential” amino acid means it cannot be synthesized by the body; instead, it must be ingested through diet.

Prior research has indicated that methionine is important for the activity of certain immune cells, most notably T-cells, which are centrally involved in driving the inflammation that causes damage to the nervous system in MS.

Previous studies, including another also presented at the ACTRIMS meeting, have shown that caloric restriction can impact T-cell metabolism, reduce inflammation, and lessen the severity of MS.

But, according to Larochelle, given the difficulty for humans to follow a caloric restriction diet, a better approach would be methionine restriction. “Methionine restriction without caloric restriction mimics benefits of caloric restriction and is better tolerated, possible to apply to humans and shows greater impact on inflammation,” she said.

Larochelle and colleagues hypothesized “that methionine restriction could improve neuroinflammation [inflammation of the brain and/or spinal cord] such as seen in MS,” by modulating the activity of T-cells, she said.

First, through experiments in vitro (using cells in dishes), the team demonstrated that activated T-cells have increased expression of genes related to methionine metabolism. They also showed that when T-cells were deprived of methionine they were less active — the cells divided less, and they produced less inflammatory molecules, in particular interleukin-17 (IL-17), which has been implicated in MS.

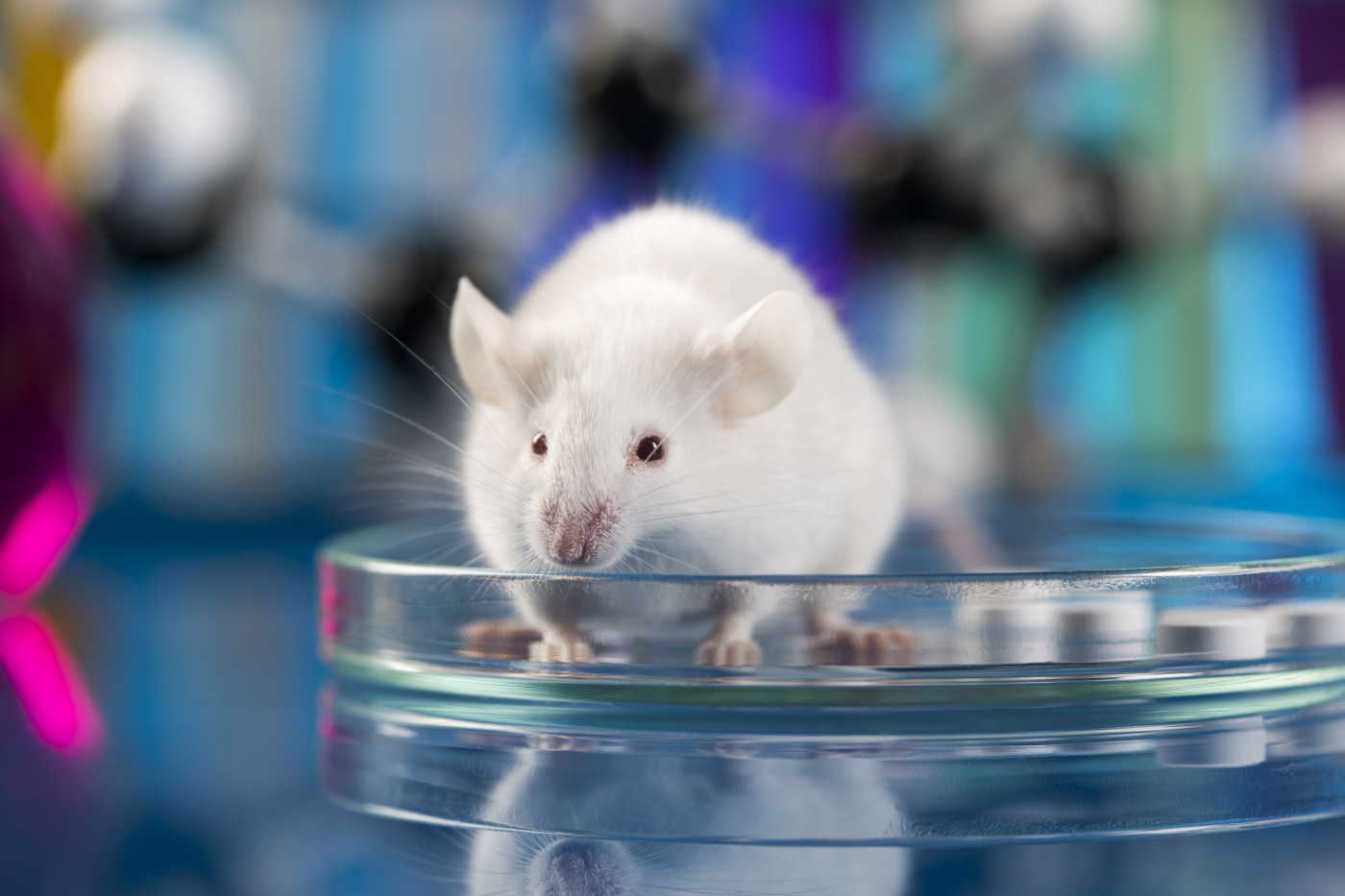

Researchers then tested the effects of altered methionine intake in vivo using a mouse model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse commonly used as a model for MS.

Reduced methionine intake lessened the onset of neurological symptoms in EAE mice. This was accompanied by reduced levels of immune cells, particularly IL-17-producing T-cells (called Th17 cells) in the mice’s brains.

The impact of reduced dietary methionine was generally more pronounced in male mice than in females. In a spontaneous model of EAE, reducing dietary methionine nearly abrogated the disease entirely in males.

Dietary methionine reduction “was beneficial in both [sexes], but seemed to be more beneficial in males than in females,” Larochelle said. She noted, however, that these are preliminary results; ongoing replication experiments are underway to confirm the findings.

Larochelle noted that the typical diet in western countries is generally high in methionine, as compared to other diets. She said Mediterranean, Japanese, and vegan diets tend to be comparatively low in methionine. Of note, beef, poultry, seafood, and pork are important sources of methionine.

The team then tested the effects of increasing the intake of methionine.

In preliminary tests in EAE mice, increased methionine intake did not affect the onset of neurological symptoms in females. However, in males, there was some early evidence that “excessive methionine intake might be associated with a higher incidence of disease,” Larochelle said.

There also was early evidence that excessive dietary methionine alters the course of disease in females, as the animals showed a poorer recovery after early relapses. Further experiments to validate and expand on these results are ongoing.

In additional experiments, researchers determined that reducing methionine intake led to changes in how T-cells’ DNA is packaged within the cells’ nucleus by modulating a process called histone methylation. Methionine is an important nutrient involved in this biological process.

Collectively, the findings indicate that “methionine restriction and pharmacological intervention targeting the methionine cycle could represent a new therapeutic avenue in MS,” Larochelle concluded.