Study Finds Myc Gene Can Boost Efficiency of Myelin-repairing Cells

Written by |

Increasing the activity of a gene called Myc can make oligodendrocyte precursor cells, or the cells that repair myelin, more efficient — “ground-breaking research” that could have implications for advancing MS treatments, according to a new study by Cambridge researchers.

The study, “Myc determines the functional age state of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells,” was published in the journal Nature Aging.

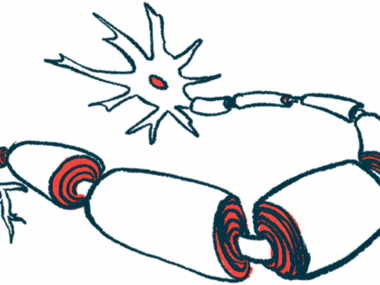

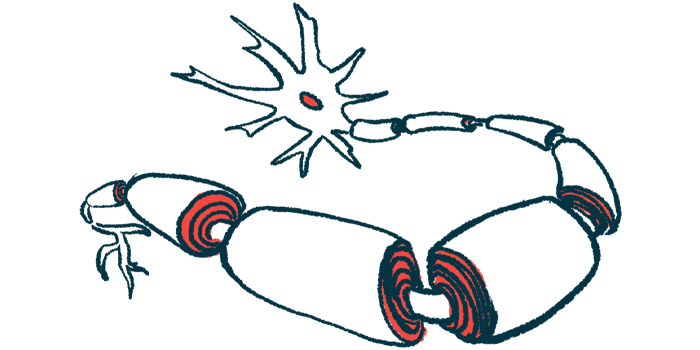

Myelin is a fatty substance that is wrapped around nerve fibers and helps them send electrical signals more efficiently, sort of like insulation around a metal wire. In multiple sclerosis (MS), the body’s own immune system launches an inflammatory attack that damages the myelin around nerves.

When myelin gets damaged, a type of stem cell called oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) can be activated to help repair the damage. OPCs can grow and differentiate into oligodendrocytes, which are the cells chiefly responsible for making myelin.

While OPCs can be activated to repair myelin, this process grows much less efficient as a person gets older. The reasons for this age-related change in OPC activity are not well-understood.

Now, scientists at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. have shown that the age-related activity of OPCs is largely dependent on the expression of a gene called Myc.

Myc codes for a protein known as a transcription factor — a type of protein that can affect which genes are “read” within the cell, thereby altering cell activity. In particular, Myc is known to promote cells to divide more actively and generally promote a more “stem cell-like” state.

In a series of experiments conducted in cell dishes and in mice, the researchers showed that old OPCs engineered to express high levels of Myc behaved much more like young cells. In other words, the OPCs were able to respond to damaged myelin more effectively.

Consistently, when young OPCs were engineered to have low Myc levels, they responded less effectively, like old cells would.

“The prospect of changing the age state of OPCs so they can regenerate throughout life … is fantastic news for regenerative medicine and chronic demyelinating diseases like MS,” Robin Franklin, PhD, a professor at Cambridge and co-author of the study, said in a press release.

A notable finding of this research, according to the investigators, is that aged OPCs with high Myc levels behaved like young cells when in older mice, which means that the cells are able to act “youthful” even though the environment around them remains aged.

“This challenges the narrative that it’s not possible to improve the function of aged OPCs without direct manipulation of the aged environment,” said Bjorn Neumann, PhD, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at Cambridge.

“Now we know that you can target the OPC on its own and see an improvement in [myelin] regeneration,” he added.

This research was funded in part by the U.K.’s Multiple Sclerosis Society.

“We are delighted to have funded this ground-breaking research,” said Clare Walton, PhD, the society’s head of research.

“We know people with MS urgently want us to find treatments that can protect and repair myelin. This latest discovery from Cambridge take us one step closer to that important goal,” she added.