Talk therapy found to ease fatigue in MS – with or without follow-up

Benefits of cognitive behavioral therapy sustained to end of 1-year trial

Written by |

A 20-week talk therapy program led to significant reductions in fatigue for people with multiple sclerosis (MS) — benefits that were sustained to the end of the year-long trial regardless of whether patients participated in additional booster sessions.

Such sessions were offered two and four months after the end of the initial cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, program. But researchers found that neither attending nor skipping these follow-ups had an impact on fatigue severity by the study’s end.

“No significant effect of the booster programme was found on fatigue severity … at 1-year follow-up,” the researchers wrote.

“Since fatigue severity did not increase in both conditions during the follow-up period, this study also indicates that wearing off of the positive effect of CBT on fatigue did not occur,” the team wrote.

The results were detailed in the study “Effectiveness of a blended booster programme for the long-term outcome of cognitive behavioural therapy for MS-related fatigue: A randomized controlled trial,” which was published in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal.

Will booster sessions extend benefits of talk therapy in MS fatigue?

Cognitive behavioral therapy, known as CBT, is a type of talk therapy that aims to identify patterns of thought that are unproductive or harmful, and find productive ways to break these negative thought patterns.

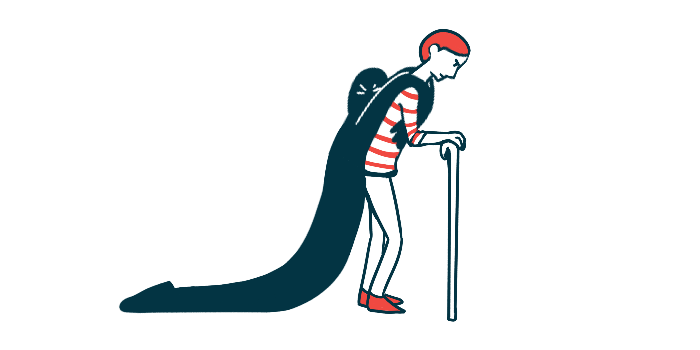

Previous studies have shown that CBT can help to ease MS-related fatigue — a “highly prevalent and burdensome symptom in multiple sclerosis,” according to the researchers.

While it’s clear that CBT can have short-term benefits, however, the longer-term effects after therapy is stopped are not clear. In fact, some studies have suggested that most patients experience worsening fatigue a few months after CBT is stopped.

Now, a team of scientists in the Netherlands sought to better understand “the mechanisms involved in the relapse in fatigue over time after CBT.” To that end, they set out to investigate if booster sessions given a few months after such a talk therapy program ended could extend its benefits in the longer term.

“Therapists and patients knew that CBT was an effective treatment, but that relapses might occur,” the scientists wrote.

Their clinical trial (NTR6966) involved 126 people with MS-related fatigue, who underwent a tailored CBT program lasting 20 weeks, or about five months, then continued to be followed for a total of one year.

The participants were mostly women (77%), had a mean age of 44.9, and had been living with MS for a median of seven years.

Results from yearlong trial involving MS patients say no.

After the initial CBT program, about half of the patients did not receive any further talk therapy. The other half underwent two sessions of “boosting,” consisting of video consults with a therapist alongside online modules practicing CBT concepts.

The results showed that, in both groups, fatigue scores lessened considerably over the course of the 20-week CBT program. Then, for the rest of the study, fatigue scores remained low — regardless of whether or not patients received the booster program.

“The absence of the expected effect of the booster programme, compared with the no booster control condition, is most likely explained by the fact that the control group did not show a relapse in fatigue severity,” the researchers wrote.

The team called that latter finding “surprising,” given that a study in which relapse was found used “the same treatment protocol and inclusion criteria.”

It would be of clinical relevance to study the outcome of CBT over a longer follow-up period, and to get a better understanding of factors mediating the long-term effects of CBT for fatigue.

One difference between the two studies was treatment duration, which was 20 weeks in this trial compared with 16 weeks in the previous one.

The team thus suggested that “spreading the same 12 therapy sessions over a longer treatment period [may have] provided more time for patients to attain their treatment goals and perhaps better sustain changes in fatigue-related cognitions and behaviour.”

Moreover, the scientists also stressed that the current trial only lasted a year in total, highlighting the need for further long-term studies.

“It would be of clinical relevance to study the outcome of CBT over a longer follow-up period, and to get a better understanding of factors mediating the long-term effects of CBT for fatigue,” the scientists concluded.