Placenta stem cells eased secondary progressive MS symptoms

Researchers tested if cells from donated placentas could be safely used in adults

Written by |

Stem cells from donated placentas appear safe and may help reduce symptoms of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a small, open-label Phase 1 clinical trial involving five patients.

“Our results suggest possible neuroprotective effects” from these stem cells, researchers wrote in “Cell therapy with placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis patients in a phase 1 clinical trial,” published in Scientific Reports. They cautioned that larger trials are needed to confirm the benefits.

In MS, the immune system mistakenly attacks myelin, the protective sheath surrounding nerve cells, disrupting nerve signals and causing damage. The disease often begins with a relapsing-remitting pattern, where periods of new or worsening symptoms are followed by a partial or complete recovery. Over time, many transition to secondary progressive MS, where symptoms gradually and steadily worsen.

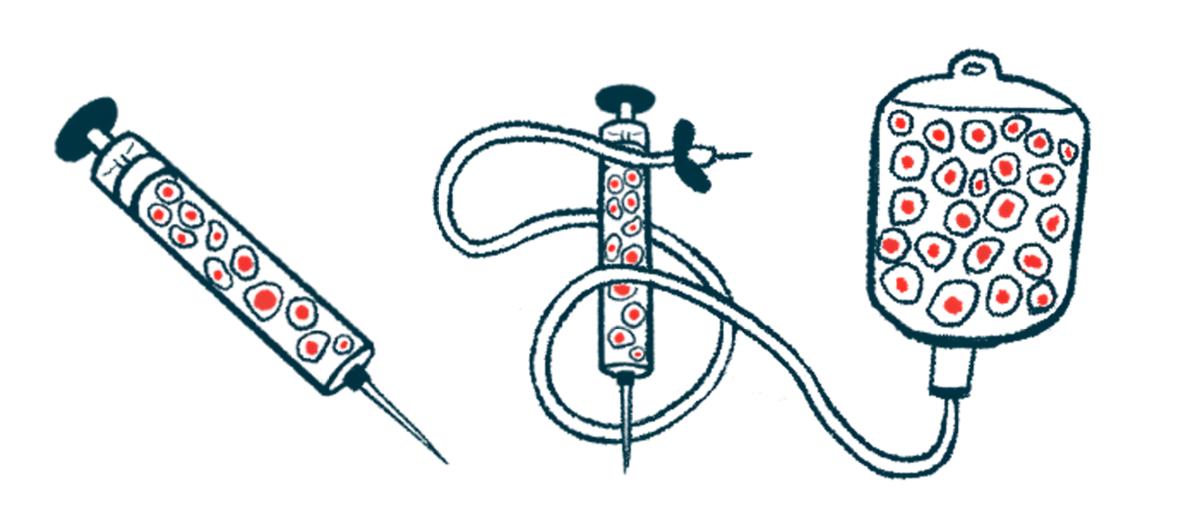

The goal of a stem cell transplant is to reset the immune system using either a patient’s own stem cells (autologous) or stem cells from healthy donors (allogeneic). Donor stem cells are typically derived from circulating blood or bone marrow, but can also be collected from other tissues, such as the placenta.

The procedure begins with chemotherapy to destroy the patient’s existing immune system. After this, previously collected stem cells are infused back into the body to regenerate the immune system. These cells can develop into various cell types and help to rebuild a new immune system that’s less likely to attack nerve cells. The process is intended to reduce MS symptoms and slow disease progression.

Improved symptoms

In a Phase 1 clinical trial (NCT06360861) led by Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Iran, researchers tested whether stem cells from donated placentas could be safely used in adult patients diagnosed with secondary progressive MS by monitoring the side effects over six months after a transplant. They also assessed the initial treatment’s efficacy.

Five patients receiving off-label treatment with rituximab which is marketed as Rituxan, among other names, and is also available as biosimilars, took part. All had disease durations of more than two, but less than 16 years. Before the transplant, their Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores ranged from 5.5 to 7, indicating a level of disability severe enough to prevent daily activities or require a wheelchair.

There were “no severe complications” from the transplant, the researchers wrote. Two patients had mild headaches, but these went away with acetaminophen, a pain reliever.

The patients’ EDSS scores decreased in the first month after the cell injection. By the third month, two patients showed a continued decline in their scores, while the remaining ones maintained stable levels.

After the transplant, the patients performed better on cognitive and psychological tests, indicating better mental function. They also tended to report less fatigue, a common symptom of MS. Functional MRI scans showed stronger connections in areas of the brain important for memory, spatial processing, and cognitive functions.

Blood tests showed a reduction in the number of B-cells, that is, immune cells responsible for producing antibodies, which may be overactive in MS, and lower levels of inflammatory proteins over the three months after the transplant. Levels of IL-10, a protein that helps reduce inflammation, increased.

Still, the trial wasn’t designed to test effectiveness, noted the researchers, who said small and larger, controlled Phase 2 trials should confirm the preliminary results of using placenta-derived stem cells, which may have “therapeutic potential in MS.”