Some Forms of MS Might Be Treatable with Hematopoietic Stem Cells

Written by |

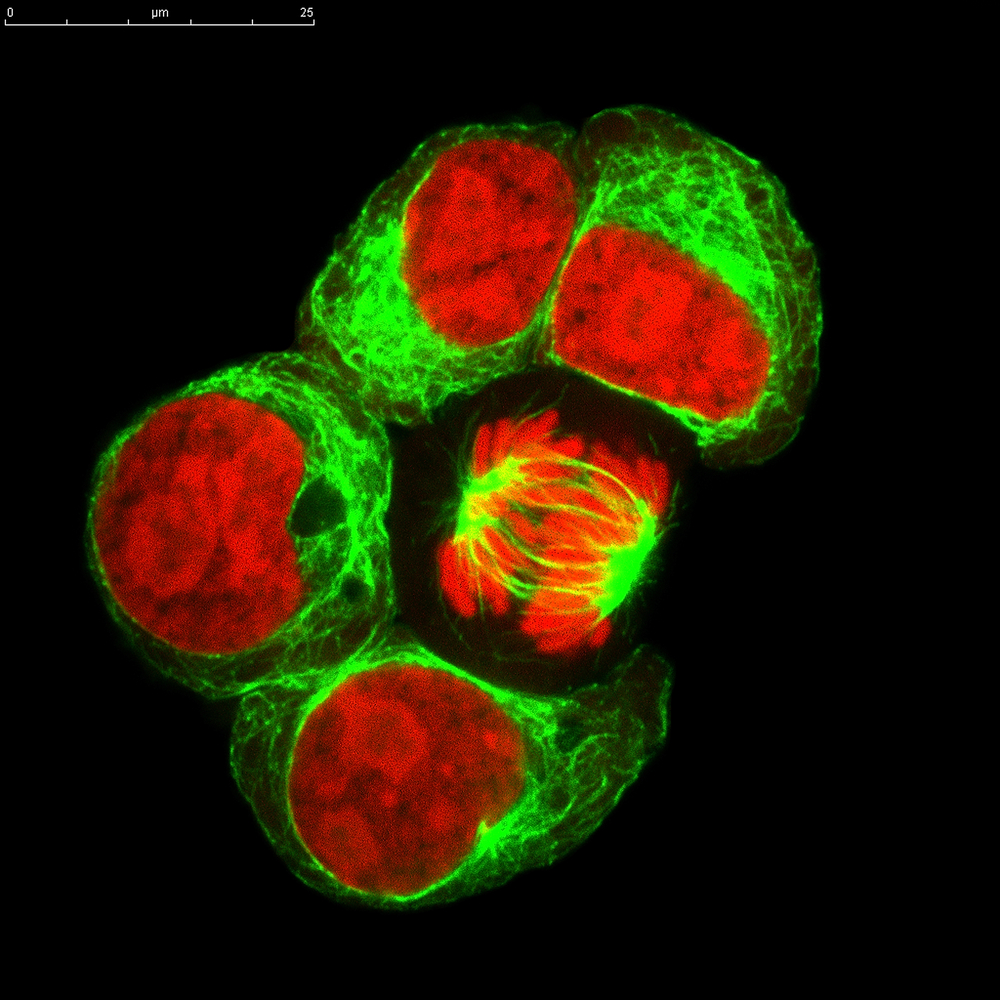

Clinical trials suggest that hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), a common treatment for bone marrow and blood cancers, could also help people with multiple sclerosis (MS). The technique involves harvesting new, undeveloped blood or bone marrow (hematopoietic) cells, typically from the person affected with the disease (autologous). The goal is to remove the faulty cells and replace them with new, cancer-free cells.

In MS, the immune system launches an attack on the body’s own myelin, mistaking it for a foreign invader. The damage to the myelin, in turn, hinders the ability of nerves to conduct impulses, and results in difficulties that include movement, vision, sensation, pain, and cognition. Available treatments focus on addressing disease symptoms, but stem cell replacement aims to restart the misdirected immune system, preventing the actual cause of the disease.

A recent article, published by researchers in Australia, reviewed whether HSCT could become an MS clinical treatment. In the article, “Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: is it a clinical reality?” that appeared on Jan. 16, 2016, in the journal Stem Cell Research and Therapy, Maha M. Bakhuraysah of Department of Medicine, Monash University, and colleagues discussed studies supporting the MS stem cell approach. According to the authors, “preclinical data derived from animal models of MS … have provided clear identification of multipotent stem cells that can reconstitute the immune system to override the autoimmune attack of the central nervous system.” However, patients must be carefully selected to determine those most likely to respond to the treatment. Autologous human stem cell therapy, they note, “is considered to be a sledgehammer approach for treating MS patients, [but] one that will be astoundingly effective when used on appropriately selected patients.”

For example, some of the treatments used to remove the diseased immune system are extremely toxic, and may not be tolerated by elderly patients. MS type may also determine whether a patient should undergo the treatment. One trial demonstrated that people with active MS in particular responded to treatment. Other research indicates that disease in patients with extremely high levels of disability may continue to progress despite stem cell replacement. Because several different approaches have been used in clinical trials, the researchers note that these observations are preliminary and may apply to specific treatments.

Another important factor includes the purity of the stem cells obtained. Cells can be sorted and selected according to size and shape, and through the use of antibodies that specifically recognize the hematopoietic stem cell. Purity is an important part of the treatment, since the hematopoietic stem cells make up only 0.01% of the body’s nucleus-containing cells and the replacement cells should include only immature cells, and not mature cells because of their chance of restarting the disease.

In conclusion, the authors said that “HSCT is a plausible treatment paradigm for MS patients.” The therapy as an MS treatment is still in the early stages, but many trials have shown positive results. The authors emphasize the need for more studies examining which patients will best respond to specific stem cell treatments.