Study Draws Reverse Link Between Number of a Patient’s MRI Scans a Doctor Checks and Worsened-MS Declarations

A new study draws a reverse link between the number of MRI scans of multiple sclerosis patients who are on interferon-beta 1a and doctors declaring there is evidence of the patients’ disease worsening.

When doctors looked at one scan, rather than multiple ones, they were more likely to say that a patient’s disease had failed to progress.

The study applied to relapsing-remitting, or RRMS, patients. The treatment, also known as IFN β-1a, is marketed under a number of brand names.

Researchers published their research in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences. It was titled “Early MRI results and odds of attaining ‘no evidence of disease activity’ status in MS patients treated with interferon β-1a in the EVIDENCE study.“

“No evidence of disease activity,” or NEDA, is one of the terms doctors use to assess MS patients’ condition. It refers to no signs of the disease worsening, including no indications that patients have had relapses or that their level of disability has advanced.

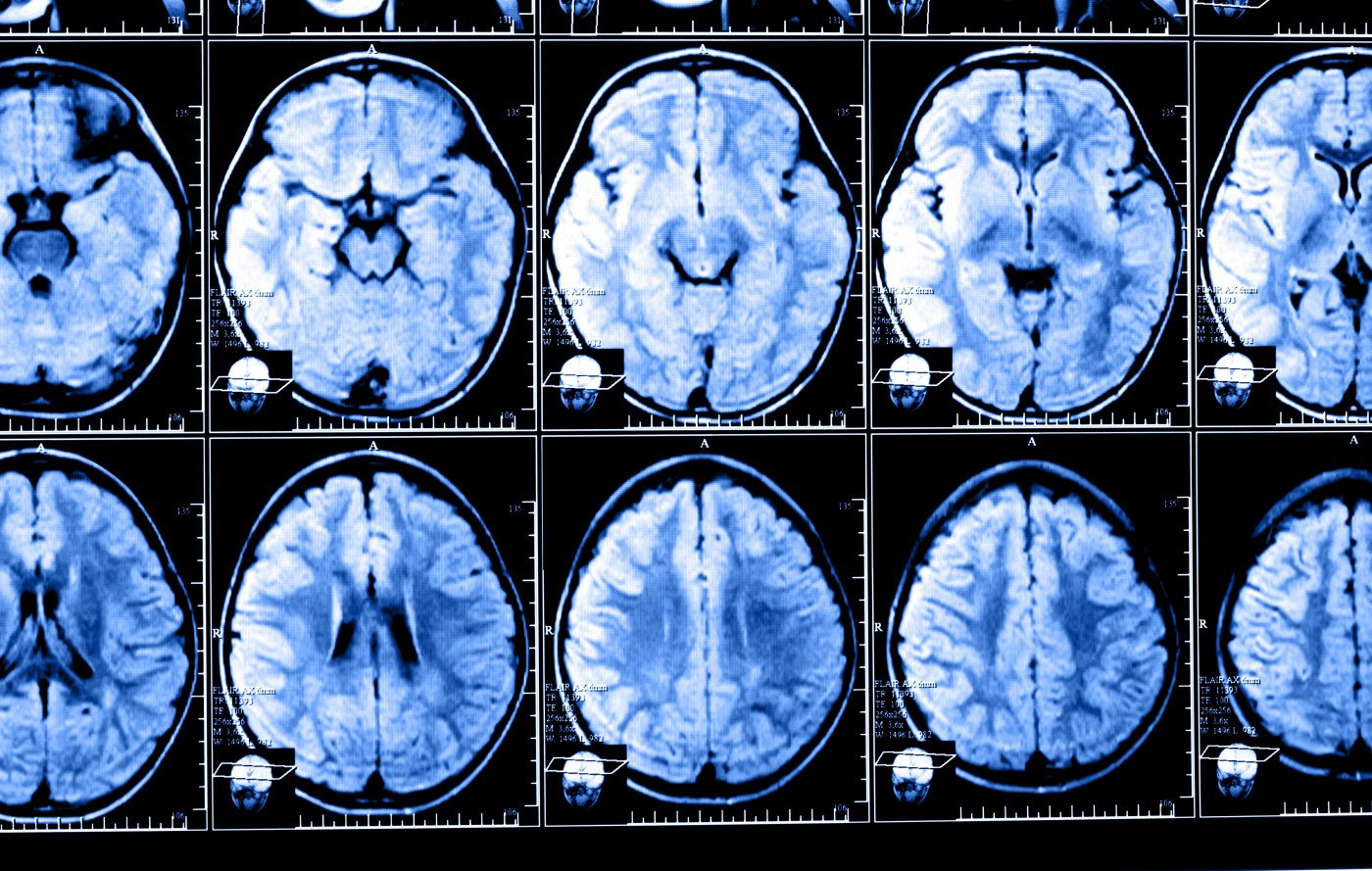

Scientists have used the designation in a number of trials evaluating the effectiveness of relapsing MS treatments. A NEDA assessment relies on sensitive magnetic resonance imaging information. This makes it important for scans to be done in a standard way.

Researchers looked at evidence from a clinical trial of interferon-beta 1a as a treatment for RRMS patients to see if they could make a connection between the number of MRI scans the patients had and how many received a NEDA designation. The trial was named EVIDENCE, for EVidence of Interferon Dose-response: European–North American Comparative Efficacy.

The MRI-related analysis of the trial results covered three factors: the number of scans that patients had, the number of patients who received a NEDA designation at 24 weeks or beyond, and the characteristics of patients’ diseases that showed up on MRI scans before and after treatment.

Those who had conducted the trial had randomly assigned RRMS patients to receive either three injections of IFN β-1a a week to the skin, or one injection a week to muscle. Skin injections proved more effective than muscle injections, the study concluded.

Using the study’s findings, the researchers who wondered about a connection between number of MRI scans and NEDA designations checked for links in both the skin-injected and muscle-injected groups.

The analysis showed that a higher percentage of patients in the skin-injected group received a NEDA designation than in the muscle-injected group.

But researchers discovered a reverse connection between number of MRI scans and a NEDA designation 24 weeks after the start of treatment. Doctors who analyzed all of the monthly MRI scans that patients received through the 24 weeks gave only 34 percent of them a NEDA assessment. In contrast, doctors who analyzed only one scan — the one at week 24 — gave 60 percent of those patients a NEDA designation.

“Including only the MRI scans at 24 weeks resulted in absolute increases of approximately 20 percent more patients achieving NEDA, compared with including all monthly scans up to that point,” the researchers wrote.

Overall, the findings supported the notion that RRMS patients who received skin-injected IFN β-1a came out better on early MRI measures of disease activity and NEDA than those who received the therapy in muscle.

The team said studies that include more MRI scans might produce a more reliable result.