Atrophy of Brain Lesions Predicts Disability in MS, 10-year Study Finds

Atrophy (shrinkage) of brain lesions correlates with physical disability in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), new research reports.

The study, “Atrophied Brain Lesion Volume: A New Imaging Biomarker in Multiple Sclerosis,” was published in the Journal of Neuroimaging.

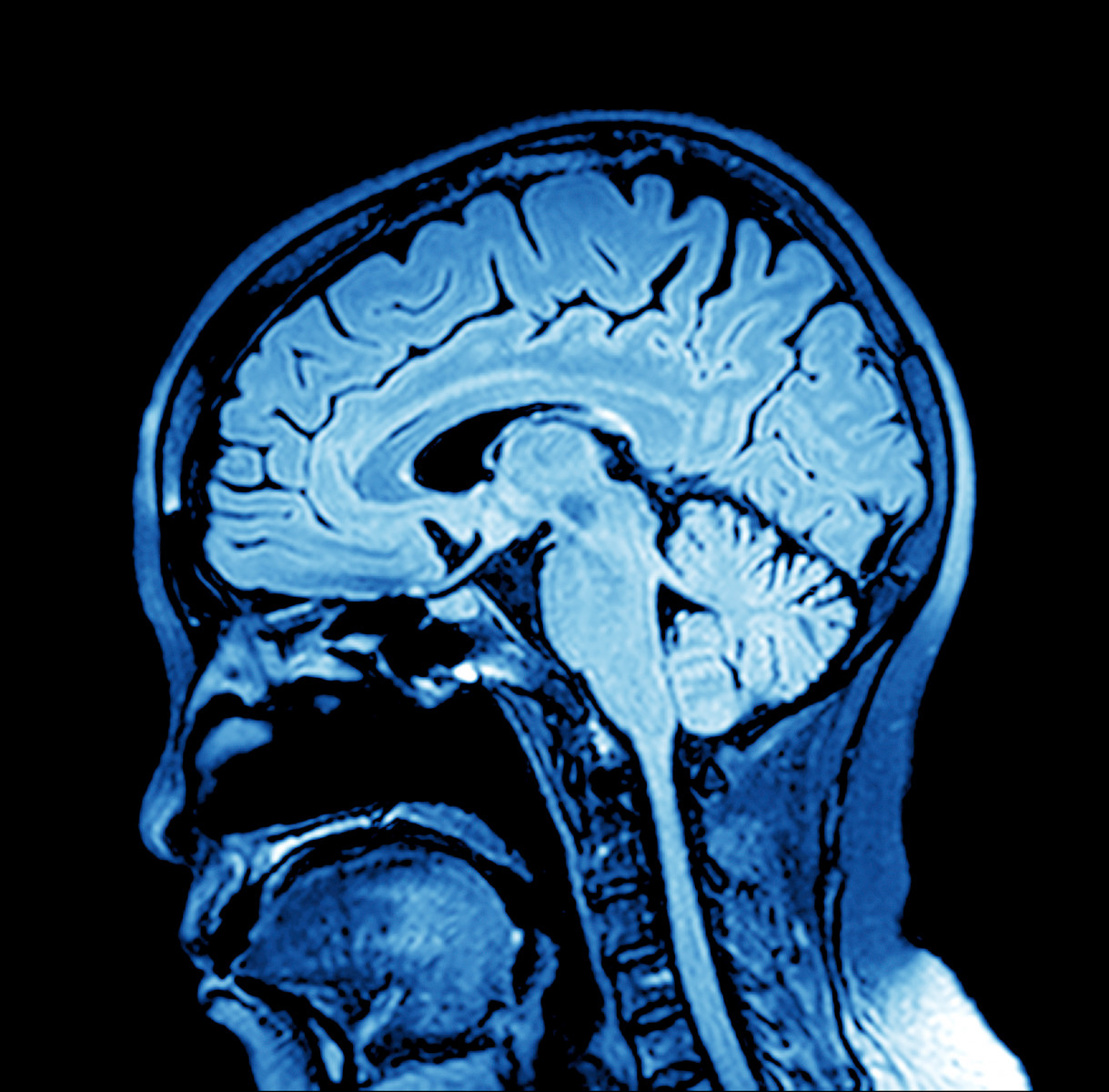

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are used routinely on MS patients to track new lesions and the growth of existing ones, which have long been regarded as indicators of disease progression. Approval of a new medication typically depends on its ability to reduce the number of brain lesions over 24 months.

However, researchers now suggest that the disappearance of lesions may indicate pathological change, such as atrophy, as well as beneficial alterations, including resolution or repair of myelin (the protective layer of nerve fibers which is typically damaged in MS patients).

Focusing on pathological changes in brain lesions, the scientists examined lesions observed in prior scans, but later replaced by cerebrospinal fluid (the liquid filling the brain and spinal cord). This opposed the traditional approach of examining new lesions, they noted.

Discuss MS treatments, research, and much more in the MS Forums

“The big news here is that we did the opposite of what has been done in the last 40 years,” Michael G. Dwyer, PhD, first author of the five-year study, said in a press release. “Instead of looking at new brain lesions, we looked at the phenomenon of brain lesions disappearing into the cerebrospinal fluid.”

Specifically, investigators compared the rate of lesion loss due to atrophy to the appearance or enlargement of lesions both at the start of the study and at five or 10 years of follow-up.

Conducted at the University at Buffalo (UB) in New York, the five-year study included 192 patients with either the most common form of MS, relapsing-remitting MS (126 patients), progressive MS (48), or clinically isolated syndrome — the first episode of inflammation and loss of myelin, but not yet meeting the criteria for MS.

The team found that unlike new or enlarged lesions, the amount of atrophied lesion volume correlated with clinical disability as assessed by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), a widely used method to quantify disability in MS.

Similar results were found in a 10-year study of 176 patients conducted in a collaboration between UB researchers and scientists at Charles University, in the Czech Republic. This 10-year research was presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) in Los Angeles, California, in April.

“We didn’t find a correlation between people who developed more or larger lesions and developed increased disability,” Dwyer said, “but we did find that atrophy of lesion volume predicted the development of more physical disability.”

When dividing the analysis by MS types, the scientists found that patients with relapsing-remitting MS had the highest number of new lesions, while those with progressive MS (the most severe subtype of the disease) had the most pronounced atrophy of brain lesions.

“Atrophied lesion volume is a unique and clinically relevant imaging marker in MS, with particular promise in progressive MS,” the researchers wrote.

“Paradoxically, we see that lesion volume goes up in the initial phases of the disease and then plateaus in the later stages,” said Robert Zivadinov, MD, PhD. Zivadinov is senior author of the five-year study and first author of the 10-year research. “When the lesions decrease over time, it’s not because the patients’ lesions are healing but because many of these lesions are disappearing, turning into cerebrospinal fluid.”

Also of importance, Zivadinov noted, was the finding that atrophied brain lesions were a better predictor of disability progression than whole brain shrinkage, which is the most accepted biomarker of neurodegeneration in MS.

“Our data suggest that atrophied lesions are not a small, secondary phenomenon in MS, and instead indicate that they may play an increasingly important role in predicting who will develop a more severe and progressive disease,” Zivadinov concluded.