Podocalyxin Helps Protect Blood-brain Barrier During Inflammation, Mouse Study Shows

Podocalyxin, a protein found in cells lining the interior of blood vessels, is key for maintaining the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) in mice with systemic infection, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), a study shows.

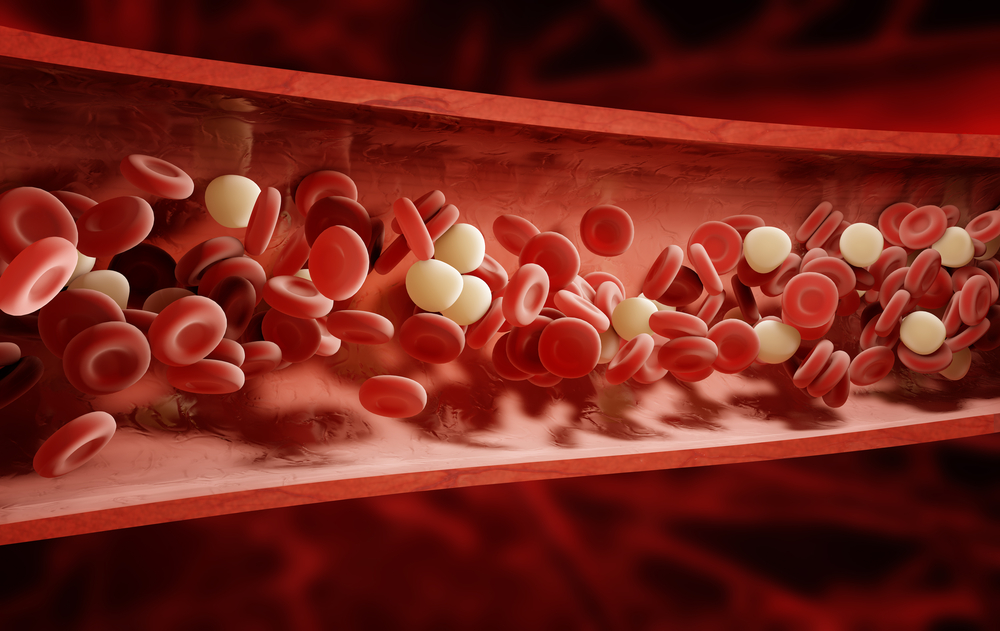

Disruption of the BBB is a hallmark of various disorders, including MS. This barrier is a natural, highly selective membrane that shields the central nervous system with its cerebrospinal fluid from the general blood circulation. When damaged, the BBB can no longer prevent immune cells and large molecules from entering the central nervous system, which may trigger inflammation and damage to neurons.

The study, “Podocalyxin is required for maintaining blood–brain barrier function during acute inflammation,” was published in the journal PNAS.

Podocalyxin is a protein found universally in most blood vessels in adult vertebrates; however, its function has not been thoroughly assessed.

Researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) studied the effects of the loss of podocalyxin in human endothelial cells — which line the interior of blood vessels — grown in the lab, and in mouse models of inflammation.

They detected podocalyxin at high levels in the BBB.

The team deleted the gene providing instructions for podocalyxin in the brain, and measured the BBB’s function in steady-state (normal) conditions and after treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) — a bacterial protein that induces systemic (whole-body) inflammation.

They found that the protein was required to strengthen blood vessels by promoting the formation of cell-cell interactions essential to establishing the cell’s barrier function.

“These findings are incredibly exciting,” Jessica Cait, a graduate research student at the Biomedical Research Centre at UBC and the study’s first author, said in a press release. “For the first time, we have been able to show that this protein is critical to the integrity of the blood-brain barrier.”

Results showed that while the lack of podocalyxin under steady-state conditions appeared to have no detrimental effects on the BBB, the protein was required to maintain proper barrier function during inflammation.

“Until now, the function of this protein was a mystery,” said Michael Hughes, PhD, co-corresponding author and a research associate at the Biomedical Research Centre, UBC. “Nobody thought to look at this as something controlling the blood-brain barrier.”

The enzyme thrombin is a potent inducer of leakage in blood vessels. Moreover, thrombin cuts adhesion molecules that connect myelin — whose loss contributes to MS — to nerve fibers. Research shows that stopping thrombin’s release in the brain could prevent myelin loss.

Thrombin activity is partly mediated by a family of G protein-coupled protease activated receptors, including the PAR-1 protein. To further assess the impact of BBB disruption in mice depleted for podocalyxin, the researchers treated the animals with an agonist of PAR-1 following treatment with LPS.

Results showed that after the administration of the PAR-1 agonist, the animals showed an immediate loss of voluntary motor control.

“These mice became completely immobile for a period lasting an average of 5 min, followed by a rapid return to full activity and normal behaviour,” the researchers wrote. This was linked with the ability of the agonist to cross the BBB.

These findings suggest a key role for podocalyxin in maintaining the integrity of the BBB under inflammation conditions, and its potential as a therapeutic target for the manipulation of the BBB’s permeability in diseases such as MS.

“A significant hindrance to treating neurodegenerative diseases at the moment is that most drugs can’t cross the blood-brain barrier,” said Kelly McNagny, PhD, the study’s lead author and a professor in UBC’s department of medical genetics. “But if we are able to induce transient opening of the blood-brain barrier, that could allow us to deliver treatment directly to brain tissue.”