Entropy in MS Patients’ Brains Seen to Mirror Level of Disability

Written by |

A recent study published in the journal PLOS ONE described a new technique with the potential to spot brain changes in multiple sclerosis (MS) before the onset of symptoms. The technique, which measures brain dynamic activity and brain entropy, may lead to the development of diagnostic — and possibly prognostic — biomarkers for MS.

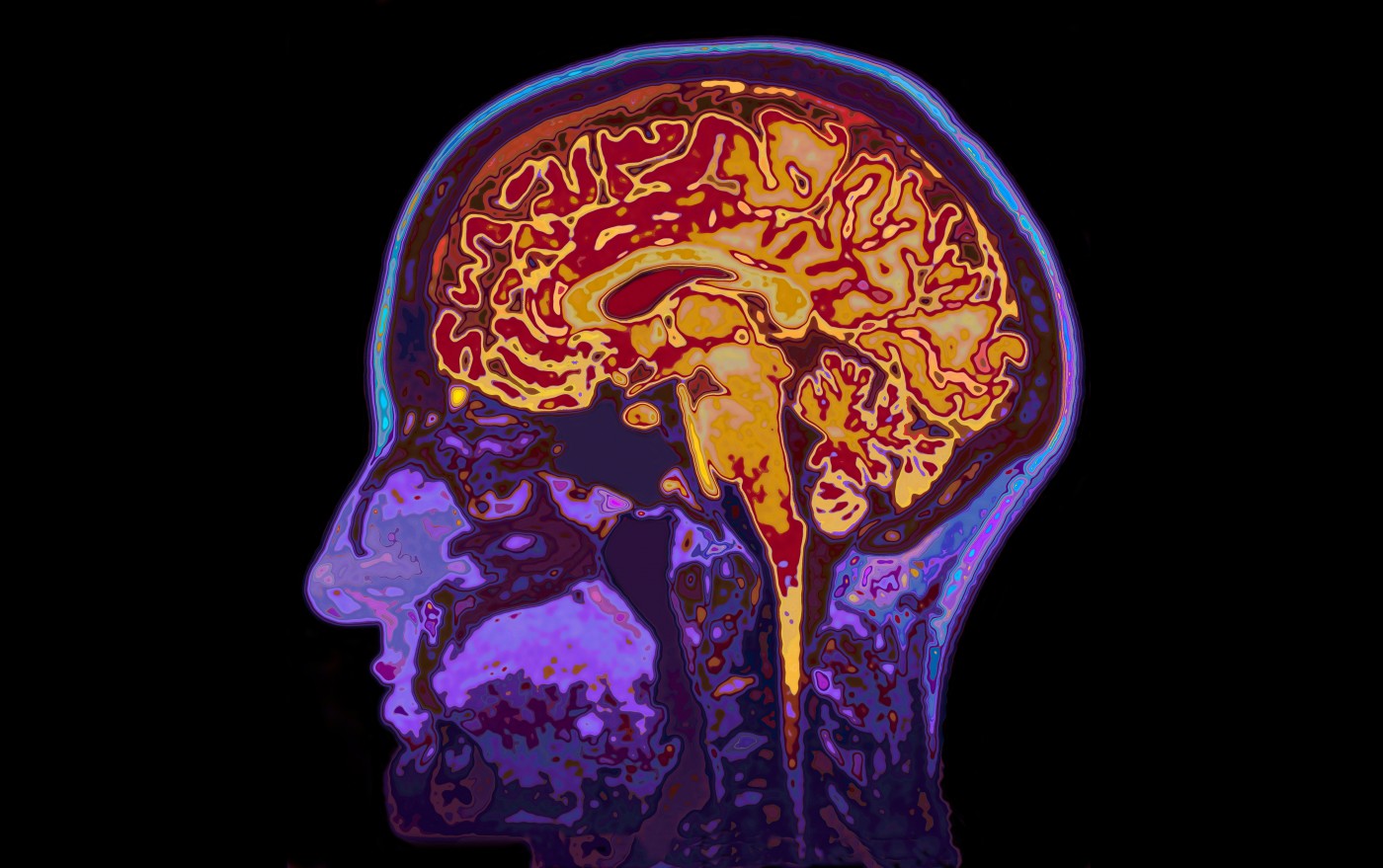

The use of brain imaging in MS has been increasing over the past decades, with structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) being able to detect changes in the brain’s white matter and identify sites where degeneration is present. Disease progression can be monitored with sMRI.

Functional MRI (fMRI) — a technique that studies brain function while a patient performs a task — has also been used in MS. Task-related activity, however, only accounts for a 5% increase in brain energy consumption — the characteristic fMRI measurements rely on. Both these techniques, therefore, are not sensitive enough to detect the small changes in brain structure and function occurring at the beginning of the disease.

Instead, research interest has turned to measurements of differences in spontaneous brain activity, accounting for the majority of brain energy consumption. Fuqing Zhou and colleagues from the Nanchang University, Jiangxi Province, China, combined fMRI — measuring spontaneous brain activity — with a statistical method assessing the randomness of a system. The study, titled “Resting State Brain Entropy Alterations in Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis,“ was performed in collaboration with a number of Chinese institutions and the University of Pennsylvania.

The entropy, or irregularity, of a biological system is an index of its state of health. Higher irregularity means higher unpredictability, indicating that a system may be more vulnerable to internal or external disruptions.

Brain entropy is a relatively new measurement, suggested to be useful in characterizing resting-state brain activity. Other studies have shown that patients with schizophrenia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as older individuals, have deviations in their brain entropy patterns. But, until now, brain entropy has never been measured in MS.

The team enrolled 34 patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and 34 healthy controls, and found that brain entropy was higher in three brain regions in patients: the supplementary motor area (SMA), right prefrontal cortex, and right angular gyrus. They also observed lower entropy levels in five regions: the right precentral operculum (PrCO), left middle temporal gyrus (MTG), bilateral parahippocampus (pHIPP), brainstem, and right posterior cerebellum (pCB). Overall, these brain regions are employed in motor planning, integration and execution, spatial coordination, cognitive control, and memory function — areas corresponding to the main symptomatology in MS.

The team further found that alterations in some of the measurements correlated with scores of the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) and the modified fatigue impact scale 5 (MFIS-5). Specifically, the authors mention a strong association between alterations in SMA and EDSS scores, meaning that these changes are directly linked to the disease and are unlikely to be explained by other factors. Along these lines, researchers suggested that the brain entropy level was predictive of impairment.

The authors noted that the lower brain entropy levels found in some regions may be a sign of compensatory mechanisms in these areas. Supporting this idea, decreased entropy in certain areas was associated with less severe disease and lower levels of fatigue. To confirm the validity of the method, the team also showed that higher entropy was associated with higher levels of tissue damage.

The technique, particularly if expanded to measurements of entropy in the spinal cord, may be useful for associating MS-related disability, fatigue, and tissue damage, and could be further developed to be used as a predictive tool in MS.