Smartphone Typing Patterns May Be Tool for Monitoring MS Progression, Study Finds

Written by |

Typing patterns in daily smartphone use show clinically relevant changes over time in people with multiple sclerosis (MS), but not among healthy individuals, a study shows.

Notably, these variations often coincided with clinically meaningful changes in measures of disease activity, disability, and/or fatigue in MS patients with and without changes in brain lesions.

The findings suggest that analyzing MS patients’ typing patterns over time may be an objective, continuous way to monitor disease progression — in contrast to standard, occasional clinical assessments. Tracking such smartphone typing patterns could potentially offer early clues of disease worsening and help physicians make better and more timely treatment decisions, the investigators said.

These results are a “first promising step” toward using keystrokes and other typing patterns to help detect clinical changes in people with chronic diseases like MS, James Twose, the study’s first author, said in a press release.

Twose is a data scientist at Neurocast, a Dutch company focused on transforming everyday digital interactions into approved, objective, and unobtrusive measures of disease activity. Neuocast owns the smartphone app used to collect the typing pattern data in the study.

“The dream is prediction,” Twose said, noting that “if there is some semblance of predictability, the joy would be to forecast the disease in a similar way you do with weather.”

The study reporting these findings, titled “Early-warning signals for disease activity in patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis based on keystroke dynamics,” was published in Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science.

Objective measures of disease activity in chronic conditions such as MS are critical in helping clinicians to track disease progression and assess patients’ responses to treatments or interventions.

The current “gold standard,” or best available measures, for evaluating changes in MS activity focuses on a patient’s MRI brain lesions, disability, and motor skills — all of which require clinic visits, a trained specialist, and oftentimes burdensome travel and/or tasks.

As such, these measures limit the frequency at which a patient’s disease state and progression are assessed, typically to once every three months to once a year. This is far from ideal, however, given that MS often shows highly variable disease courses among its patient population and even within individual patients.

“Additionally, given the nature of the data (infrequently sampled and, therefore, in low abundance), these data are analyzed on a group level,” the researchers wrote, noting that this method “irons out variation on the individual level.”

Typing pattern data, conversely, are easily assessed measures that can be analyzed on a continuing and individual basis.

“A more patient centric and individualized approach could increase the data quality and quantity while improving the lives of individuals living with chronic diseases,” the team wrote.

In their study, Twose and his colleagues at Neurocast and the Amsterdam University Medical Centers, in the Netherlands, showed that analyzing an MS patient’s typing patterns (also known as keystroke dynamics) over time may be used to detect potential changes in disease progression.

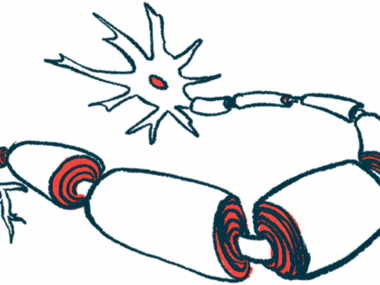

A person’s typing pattern — how quickly or slowly the individual types, the amount of time between letters typed, and the number of mistakes made and corrected while typing — is unique, and profound variations in this pattern may reflect neurological changes.

“In chronic diseases like MS and Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, there is inherent worsening over time,” Twose said. “When it comes to typing, you need all your faculties to do this well. We notice when you have problems with that.”

The team first analyzed changes in the smartphone typing patterns of 58 people, including 13 MS patients with variations in MRI brain lesions, 21 MS patients without these changes, and 24 healthy individuals (used as controls) over one year.

The participants’ typing pattern data were passively collected through Neurokeys, a Neurocast smartphone app that replaces a user’s original keyboard and “tracks how but not what the user is typing,” the researchers wrote.

These data were analyzed with a specific method called non-linear time series analysis to identify clinically relevant changes in keystroke dynamics.

Results showed that while the typing patterns changed daily for all participants, clinically relevant changes were only observed in MS patients, both with and without variations in brain lesions.

The researchers then assessed whether these clinically relevant changes in typing patterns preceded or coincided with clinically meaningful changes in measures of disease activity, disability, fatigue, and quality of life.

The findings showed that indeed some of the variations in keystroke dynamics coincided with clinically meaningful changes in outcome measures in both groups of MS patients. Such variations thus might be seen “as EWS [early warning signals] for changes in disease activity of the patient prior to the change occurring,” the team wrote.

Taken together, “the results from this study are preliminary evidence for the use of the quantification of change in [typing patterns], a continuous, objective, noninvasive measure, as a proxy for change in disease activity and disease status of patients with MS,” the researchers wrote.

The team noted that future research should focus on improving this model, assessing the predictive nature of typing pattern changes in terms of disease progression, and broadening the use of this approach to other diseases.