Stem Cell Transplant Gaining Ground as MS Therapy Option

Written by |

Nothing was working for Jennifer Stansbury Koenig, who was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in 2010 the day before she learned she was pregnant.

The first disease-modifying therapy (DMT) Koenig started in 2013, Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate), an oral capsule developed and marketed by Biogen, made her symptoms worse, she said. Flushing began and walking became significantly harder. Since the weekend she first used that DMT, Koenig has not been able to go on the 5-mile hikes she and her husband enjoyed near their cabin in Kentucky’s Daniel Boone National Forest.

The second DMT, Tysabri (natalizumab), also marketed by Biogen, yielded the same results. The third, Copaxone (glatiramer acetate injection), marketed by Teva Pharmaceuticals, seemed to make no difference at all, Koenig said.

Part of the reason these DMTs didn’t work and seemed to exacerbate her multiple sclerosis (MS) symptoms was that remnant Lyme disease virus antibodies were hiding in her immune system, a fact she learned in December 2015.

Jennifer Stansbury Koenig’s nonprofit, HSCT Warriors, promotes awareness of the procedure for MS and autoimmune disease patients. (Photo courtesy of Jennifer Stansbury Koenig)

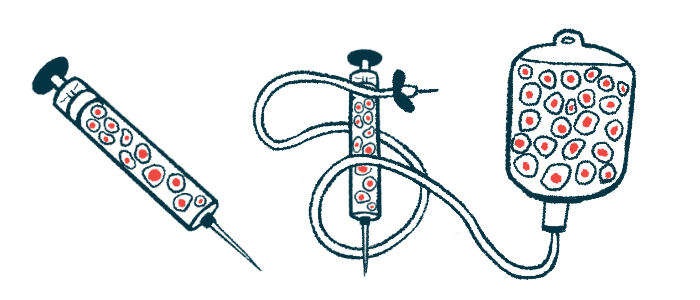

Four months later, Koenig read a magazine article about autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (aHSCT), a procedure that has historically used a patient’s own stem cells to treat blood cancers.

Koenig learned that some multiple sclerosis patients are using the procedure to halt or slow disease activity when other options fail.

She connected with Richard Burt, MD, professor of medicine at Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, an expert in aHSCT for MS patients, and editor of a recently published textbook on stem cells and other cellular therapies for autoimmune diseases. At the time Koenig contacted him, Burt was running a clinical trial (NCT00273364) that looked at the differences between aHSCT and FDA-approved DMTs. Koenig did not end up qualifying for that trial, but received the treatment on a compassionate use basis.

Trial results, published in 2019, showed that 15% of RRMS patients had a relapse five years after aHSCT, compared with 85% of those randomized to a DMT. Also, about 10% of patients experienced disease progression in the five years after aHSCT, compared with 75% on DMTs.

In the U.S., those who know about aHSCT but don’t qualify for trials often seek out doctors internationally who specialize in the procedure. Koenig said some U.S. doctors are now considering the treatment outside of clinical trials.

However, with the potential of becoming MS-free comes the dangers of aHSCT. The risky procedure harvests stem cells from a patient’s bone marrow and reinjects them into the body after the immune system is temporarily killed off by aggressive chemotherapy.

Trials show aHSCT promise, risks

Jeffrey Cohen, MD, is director of experimental therapeutics at Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research, and protocol chair for BEAT-MS (NCT04047628), a clinical trial investigating aHSCT in MS. According to Cohen, side effects of the procedure can include collateral bone marrow damage and engraftment syndrome, which causes fever, skin rashes, lung damage, low oxygen levels, and diarrhea.

Cohen said that given the risks associated with aHSCT, MS patients should try at least one DMT first.

“I don’t think most people appreciate how risky and how complicated the procedure is,” Cohen told Multiple Sclerosis News Today. “They just sort of think about what they hear is the good aspects, but it is a pretty complicated and a pretty risky procedure.”

Some patients have died from complications relating to the procedure, but for Koenig, the risk was worth it.

Koenig receives chemotherapy during her autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation process. (Photo courtesy of Jennifer Stansbury Koenig)

“I felt like I would rather die trying than to never have tried at all,” Koenig said in an interview. “Because, at the end of the day, even if the MS were to resurface and relapse, at least I will have tried.”

After being reinjected with her stem cells in the fall of 2017, Koenig said she knew the treatment had worked. She felt like her mind was clearer; neighbors who visited her in the days after her transplant noticed she was walking better. The therapy, however, hasn’t healed the lesions in the 43-year-old’s brain and spinal cord, and she can struggle with walking and returning to her previous active lifestyle.

Realizing that change wasn’t cheap. This type of treatment carries a roughly $150,000 price tag without insurance. Koenig’s insurance initially approved the treatment, which cost $125,000 in her case, but it rescinded coverage a week later. The appeals process would have taken too long and risk her chance to go through with it, as she had begun to transition into a more chronic form of MS. Family and friends stepped in to cover the out-of-pocket cost, with her parents using the money they made from selling their house to partly fund the procedure.

A couple of studies have shown initial success for aHSCT in MS patients, supporting Koenig’s experience. A paper published last year found positive results for 210 RRMS and progressive MS patients in Italy. For RRMS, 86% of patients remained alive and free of disability worsening after five years and 71% after 10 years. The figures were 71% and 57% for progressive MS patients, respectively. Three patients given transplants before 2007 died within 100 days following the procedure.

“This is really a change of the management of multiple sclerosis. It’s important that the patient and their relative[s] know that there is a chance to perform bone marrow [stem cell] transplantation,” Antonio Bertolotto, MD, a study co-author, told Multiple Sclerosis News Today. Bertolotto also is former director of the Neurology & Regional Referral Multiple Sclerosis Center at the University Hospital San Luigi Gonzaga in Northeast Italy.

A separate clinical trial (NCT01099930) at the University of Ottawa in Canada followed MS patients who underwent aHSCT over the last two decades. Trial results presented at a recent MS conference showed that no patient experienced a relapse post-transplant and disability remained stable or slightly improved after a follow-up period ranging from eight months to 20 years.

Jeffrey Cohen, MD, is a neurologist at the Cleveland Clinic and study chair for BEAT-MS. (Photo courtesy of Jeffrey Cohen)

In October, the National MS Society voiced support for aHSCT in people with very aggressive RRMS who responded poorly to DMTs.

BEAT-MS, sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is currently recruiting up to 156 adult patients at sites across the U.S and in the U.K. to compare aHSCT with the best available therapy for treatment-resistant relapsing MS. It is believed to be the only available trial for this kind of therapy in the U.S.

“We’re very interested in transplant as a treatment option, but for it to become more widely accepted, including to be covered by [insurance] payers … we think a formal study like BEAT-MS is necessary,” Cohen said.

There’s always a chance aHSCT won’t be as effective in some patients compared to others because of the individualized nature of the immune system, Harold Atkins, MD, said in an interview. Atkins is a physician in the transplant and cell therapy program at The Ottawa Hospital, who co-authored a study on the Phase 2 Canadian trial and has been involved in aHSCT since the late 1990s.

It won’t work for those with late progressive MS, Atkins added, but might be effective at reducing future relapses for patients transitioning from RRMS to progressive MS. A recent study he cited found that aHSCT did not reduce disability progression in secondary-progressive MS when compared to a low-dose immunosuppressive therapy.

Atkins said the immune system that affects MS is different in acute RRMS compared with chronic progressive MS. The procedure seems to work well for acute cases, but not so much for the latter, he said.

All physicians interviewed for this story say aHSCT works much better in earlier disease stages, before severe disability heightens the risk of complications from the procedure, or before the development of late progressive MS makes success less likely. The optimal time to introduce the treatment is still more of a question mark than a period, Cohen said, and studies like BEAT-MS will help answer that question.

Where stem cell transplant now stands

aHSCT is not approved for MS by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), meaning it cannot be marketed and distributed between states, according to Paul Richards, chief of the consumer affairs branch at the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. The regulatory agency also has issued multiple warnings about the use of stem cells for “regenerative therapies.”

Medical practitioners interested in pursuing stem cell therapy would need to ensure compliance with FDA regulations on human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based products before moving forward. The product can be used without a pre-market application to the FDA only if it meets certain requirements under the law.

Richards said care should be used and guidelines should be carefully reviewed before moving forward. He encourages patients and doctors to contact the FDA with questions specific to their aHSCT procedure.

Pharmaceutical companies don’t have much of an incentive to get involved yet because of the lack of FDA approval. Drugs used for the aHSCT procedure also have been available for a long time, Bertolotto said. For example, cyclophosphamide, a chemotherapy medication cited in the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation protocol for aHSCT in MS, was approved in 1959 and now is used under a generic name.

Bertolotto said that even though the treatment comes with risks, patients should be made aware of the option of aHSCT earlier rather than it being used as a rescue treatment after trying numerous DMTs.

There also is an economic incentive to explore aHSCT earlier for whoever is paying for the procedure, whether it be the government or private insurance, Bertolotto said. Stem cell transplant is a one-time treatment whereas typical immune-suppressing MS medications must be administered relatively frequently, he explained.

Subsequent doses of Ocrevus (ocrelizumab), an antibody therapy developed by Genentech, lead to the death of immune system B-cells but must be administered every six months, with the total annual cost topping $65,000. Assuming the patient does not relapse after aHSCT, the cost would be made up in a little more than two years.

In Italy, this procedure is considered standard care and a clinical option for MS patients. Many patients, however, aren’t aware it exists there and around the globe.

To help bridge that knowledge gap, Bertolotto, who currently runs a private MS clinic, is evangelizing aHSCT and other therapies not supported by pharmaceutical companies to patients and neurologists in his country through an emailed newsletter. The project is funded by an Italian research organization.

That’s also what Koenig is doing in the U.S. with her foundation, HSCT Warriors, which was born from a podcast of the same name launched in August 2018, where she has interviewed more than 70 patients and caregivers who experienced aHSCT. In the meantime, the nonprofit is promoting awareness of the procedure for MS and autoimmune disease patients. Her hope is that people learn about aHSCT before failing multiple treatments.

“If I had learned about HSCT sooner, I know I would have explored it as an option to halt the progression of my disease. So, ultimately, we believe people deserve the chance to make an informed decision about their care,” Koenig said.