FAQs about Ocrevus

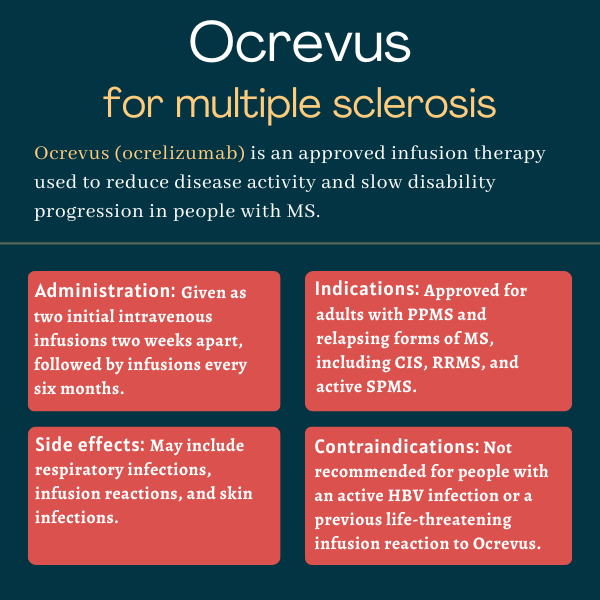

Ocrevus was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in March 2017 for the treatment of adults with relapsing types of multiple sclerosis (MS), including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting MS, and active secondary progressive MS, as well as adults with primary progressive MS.

According to animal studies, Ocrevus may cause harm to a developing fetus. Patients able to become pregnant should use contraception while on Ocrevus, and for at least six months after stopping the therapy.

There are no known interactions between Ocrevus and alcohol. However, since alcohol can interfere with some disease symptoms and medications, patients are advised to discuss with their healthcare provider whether it is safe to drink while on Ocrevus.

As each person may react differently to medications, there is no standard timeline for how soon Ocrevus starts to work. In clinical trials, Ocrevus induced a rapid and marked depletion of B-cells within two weeks after the first dose, but it may take several months for patients to experience the therapy’s full benefits.

Hair loss and weight gain were not reported as side effects of Ocrevus in clinical trials, but there have been some isolated reports of hair loss in people receiving this medication. Patients are advised to talk with their healthcare provider if they experience any such issues.

Related Articles

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by