Soft Inner Layer Surrounding Brain May Be MS Target, Study Finds

Disease-causing immune T-cells enter brain, spinal cord through membranes

Written by |

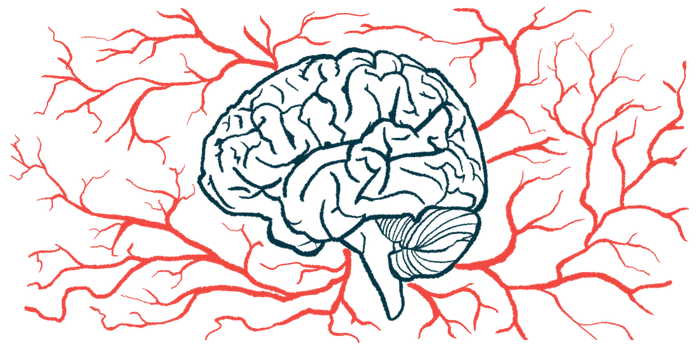

In multiple sclerosis (MS), disease-causing immune T-cells enter the brain and spinal cord through the protective soft membranes covering them, called the leptomeninges, a new study shows.

The findings “suggest that patients with MS could benefit from immunomodulatory therapies that target the leptomeninges,” the researchers wrote, noting these surrounding membranes “were highly inflamed and showed structural changes” in both “acute and chronic disease.”

The study, “Distinct roles of the meningeal layers in CNS autoimmunity,” was published in Nature Neuroscience.

MS is caused by inflammation and abnormal immune reactions against myelin, the protective sheath around nerve fibers, in the central nervous system (CNS). The CNS is comprised of the brain and spinal cord. T-cells play a central role in initiating and driving these abnormal immune responses and inflammation in MS.

Under normal circumstances, circulating T-cells do not enter into the CNS itself due to a highly-selective membrane called the blood-brain barrier. However, they are regularly found in the meninges — the protective membranes surrounding the CNS — like guards patrolling the border of a high-security installation.

Investigating the brain’s protective layers

The meninges, which help protect the delicate nervous tissue from trauma injury, can be broadly divided into two layers: a soft inner layer called the leptomeninges, and a harder outer layer called the dura.

Immunologically speaking, the outer dura has long been thought of as more “immune-friendly,” as it contains blood vessels with small openings or “windows” that allow cells and molecules to flow more freely.

“Immune cells should therefore be able to migrate through the [windowed] blood vessels without any problems,” Arianna Merlini, PhD, the study’s first author, from the Institute of Neuroimmunology and Multiple Sclerosis Research (IMSF) at the University Medical Center Göttingen (UMG), in Germany, said in a university press release.

This layer also contains lymphatic vessels, a special vascular system that collects and circulates excess fluid and waste products in the body. It is used by immune cells as pathways or “roads” to get from tissues to their natural home, the lymph nodes.

“The immune cells that have migrated into the dura can also circulate back into the lymph nodes via the lymphatic vessels after they have completed their control rounds,” Merlini said.

In turn, the blood vessels in the leptomeninges are tightly closed and lymphatic vessels are absent from this inner layer.

As such, it has long been supposed that the dura probably serves as a hub for inflammatory T-cells that infiltrate the CNS in multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases.

To learn more, UMG scientists, along with colleagues in Germany and Finland, conducted a battery of analyses in mouse and rat models of MS, as well as in brain tissue from deceased MS patients. Their goal was to understand how T-cells move from the meninges into the CNS.

Unexpectedly, in both rodent models and MS patients, the researchers found that T-cell activity in the dura remained virtually unchanged. By contrast, in the soft inner leptomeninges, there was a dramatic increase in inflammatory T-cells that could then enter the CNS.

“In the case of disease, the soft meninges and the adjacent brain tissue are … primarily affected by the autoimmune inflammation,” said Alexander Flügel, MD, the study’s co- senior author and director of the IMSF.

“Therapeutic efforts to curb autoimmune inflammation should therefore be particularly directed at the soft meninges and brain tissue. The hard meninges and their lymphatic vessels, on the other hand, should not be considered a priority target,” Flügel said.

Surprising results found

The researchers also identified two mechanisms that explain these surprising results.

First, while blood vessels in the dura were more permeable — allowing for greater movement of cells through them — vessels in the leptomeninges exhibited substantially higher levels of adhesion molecules in settings of CNS inflammation.

As the name implies, adhesion molecules help T-cells “stick” to the vessel, so they stop rolling along through the bloodstream and can instead crawl in to invade the tissue.

“The behavior of the disease-causing T-cells in the blood vessels of the different brain layers shows very clearly that the permeability of the blood vessel is not decisive for the attachment and migration of T-cells,” said Francesca Odoardi, MD, a professor at UMG and co-senior author of the study.

“The decisive factor is rather the presence of suitable adhesion molecules with which T cells can attach to the vessel wall,” Odoardi said.

The second identified mechanism involved differences in the activity of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) between the two layers. APCs, as their label suggest, present antigens, or fragments of molecules that can promote immune responses, to immune cells such as T-cells.

This process activates T-cells against that specific antigen — which in MS are self-antigens related to myelin — releasing pro-inflammatory molecules to sound the alarm.

The researchers demonstrated that APCs in the leptomeninges had more access to CNS self-antigens, and therefore were more able to activate inflammatory T-cells in the autoimmunity models. By contrast, APCs in the dura had little T-cell-activating capability.

“The distribution of brain proteins is thus strictly limited to the brain and the immediately adjacent meninges, at least in the healthy state,” Odoardi said.

“The soft meninges obviously serve as a kind of filter that limits the transmission of released brain proteins” to the outer dura, meaning that APCs in this layer “do not have access to proteins of the brain tissue,” Odoardi added.

“Our study shows the distinct participation of the different meningeal layers in CNS autoimmunity, with the dura playing a rather passive role in both acute and chronic autoimmune disease, in contrast to the leptomeninges,” the researchers wrote.

Future studies, focused on providing a more detailed characterization of the immune landscape of the human dura, are needed to “further expand knowledge on the meninges’ differential contribution to human disease,” the team added.