Writer Recalls MS Odyssey While Living on the ‘Last Frontier’

Melissa Cook moved to Alaska to teach, starting a 20-year family adventure

Written by |

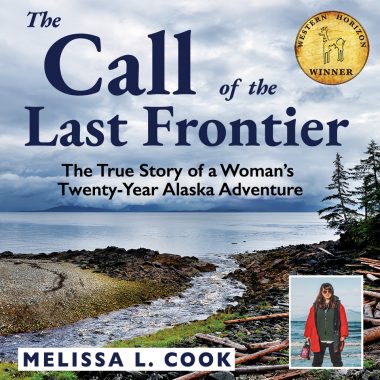

Melissa Cook moved to Alaska in 1995 before being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. She writes about her experiences there and with the disease in her book "The Call of the Last Frontier." (Courtesy of Melissa Cook)

The wing of the small aircraft dipped below the horizon, revealing a strip of sand in the middle of the Bering Sea. On one side, miles of ocean. On the other, a lagoon.

It was 1995, and Melissa Cook, her husband Elgin, and their three small children were beginning an adventure that would last 20 years. The two teachers would live in a remote town on the Alaska Peninsula with a population of 30 at the time, later moving to Prince of Wales Island along the state’s Inside Passage.

Melissa Cook standing on the beach at Nelson Lagoon in 1997, where she lived after moving to Alaska. (Photos courtesy of Melissa Cook)

“There were no stores, no medical, no anything except the [Aleut] people and they slept during the day, and were up at night,” said Cook, 55. “So it was like we were there alone.”

Cook, then in her 20s, also would soon begin battling a neurological disease.

She knew from the moment they’d landed on Nelson Lagoon that she should start keeping a record of her family’s experiences. On the first day, she filled out one post-it. After 20 years of raising a family there and managing a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), that one note grew to a shoebox full of a 1,000 post-it notes, which Cook turned into a book that she self-published through her company, Hoodoo Books LLC, in October 2021. Called “The Call of the Last Frontier: The True Story of a Woman’s Twenty-Year Alaska Adventure,” her book won the Western Horizon Award and was a finalist for the High Plains Book Award. Just under 5,000 copies have been sold.

The start of a journey with MS

Cook and her husband met in Detroit, where she grew up, and the two graduated from Black Hills State University in South Dakota together. They were drawn to Alaska because they’d heard that teachers could retire there earlier.

Melissa Cook started a YouTube channel about off-roading in Jeeps after she and her husband retired to Wyoming.

In those first two years on Nelson Lagoon and the 18 that followed on Prince of Wales Island, Cook dealt with a number of challenges. But the first was being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS).

She started showing some MS symptoms when she was 15, noticing problems with understanding what was being said to her. But she pushed any concerns about the disease to the back of her mind for several years, even though a hearing specialist and neurologist told her mother they suspected MS. After the move to Alaska, Cook said her fingertips began to tingle as if they’d been asleep for three days, then her hands and arm felt like they were burning.

When the weather permitted over her school’s spring break in 1996, Cook made the 400-mile trek by plane to Anchorage to get looked at by a chiropractor. The stress of traveling aggravated her symptoms and the tingling sensation moved to her leg.

That summer, a neurologist in Montana told her there was a 90% chance she had MS. But imaging showed only one lesion and two are typically required for an MS diagnosis.

In her third year in Alaska, Cook and her family had had enough, packing up their bags and moving to Ohio. But they only stayed a year, soon realizing the early retirement and better medical benefits offered in the Alaskan school districts were worth roughing it up north.

Eventually, problems with her vision forced Cook to seek treatment. She pushed through to finish the school year, but had to stop grading papers because she couldn’t read them. She was soon formally diagnosed with the chronic disease and was started on a steroid for optic neuritis, which addressed the issue.

“I tell people don’t suffer with MS,” Cook said. “I went almost more than half a year with no vision because I didn’t know to take steroids and it was because of where I lived.”

A chronic disease in a remote location

Living with a health issue on a thin finger of land jutting out into the Bering Sea was difficult, and traveling to a doctor was no easy feat.

Cook could see a local general practitioner, but it was an hour-and-a-half drive down a rough rock road and there was only so much he was qualified to help with. Going to an optometrist in Ketchikan meant boarding a seaplane. A visit with a neurologist required a trip to Seattle or Montana, and much later, Wyoming.

It was just as much of a challenge to get the MS medication she needed. Weather sometimes delayed shipments, which also had to be flown in via seaplane. She had to order well in advance.

Melissa Cook’s book, “The Call of the Last Frontier” was published in October 2021.

In 2008, the disease took a turn for the worse. A new brain lesion began to affect her heart, lungs, and body temperature. This came on as she was working on her PhD in school administration. Cook would have to discontinue the program.

“That is the lesion that I call the golden bullet,” Cook said. “That’s the one that you can die from.”

She took a year off of work to “prepare for my death.” Her doctor in Wyoming got her disease relapse under control and Cook returned to work, but it was never the same. She was often extremely fatigued and had memory issues. She had to keep reminders on post-it notes, even pasting some onto herself.

“I told the kids ‘when I’m as bad as the first-year teachers are going to be for you, that’s when I’ll retire,’” Cook said. “Once I reached that point, I knew that a new teacher was gonna be better than what I could do as an experienced teacher and I left.”

Looking at life through a new lens

Cook went out on medical disability in 2011, but her husband still had five years to teach. The change made her profoundly lonely — her husband and everyone around her were still working. For more than two years, she stayed home. Then a light bulb went off about her illness that changed everything.

Elgin and Melissa Cook moved to a remote part of Alaska to be teachers and lived there for more than 20 years.

“It took me 31 months to figure out that MS is not a bundle of sick days. It’s life,” Cook said. “One day I got my camera and I went outside and I went out to play. My neighbors were so excited to see me because they hadn’t seen me in a couple of years and I began living my life again.”

She started the blog MSsymptoms.me to share her experiences and offer some perspective about life with a neurological disease. Cook also posts news about the latest research.

After her husband retired in 2017, the couple moved to Wyoming. Cook was finishing a book project about life in Alaska that she had been working on, but she scrapped it that year, unhappy with how it was turning out. It took her two years before she was ready to try again.

The new effort was written partly to offer hope to people struggling with MS, to show that they can rebuild their lives even if the disease puts a wrench in their plans, as it did her teaching career.

These days, the Cooks are happily retired and the proud grandparents of four. They spend their time in Cody, Wyoming, making YouTube videos about Jeep off-road adventures. Cook is an EMT for the community and still writes her blogs, Alaska Bush Life and MSsymtoms.me.

Cook has been promoting the book since its release and recounting her experience of life with MS in remote Alaska. She appeared on the “Thriving Over Surviving” podcast in November, and she was recently interviewed for an MS News Today podcast that’s expected to air on Jan. 26. She’s also been a guest on local radio programs and was profiled in Cody Living Magazine.

Writing her book gave Cook the chance to reflect and rekindle relationships with the people she knew in Alaska. They include George Nathan, the only pilot available to fly the family out to Nelson Lagoon from Homer, Alaska, when the ferry had once broken down. Nathan, who told MS News Today he’s happy to have been mentioned in the book, said he remembered the event.

“When you are in the business you are doing stuff all the time and blends into one. I do remember the flight with Melissa,” Nathan said, noting it wasn’t every day you’d take a single-engine plane down to the end of the Alaskan Peninsula.

Cook said the book also explores her love-hate relationship with Alaska. The natural beauty was breath-taking, but the challenges were many. Even at the end, she had trouble saying farewell.

“Goodbye, Alaska. I’ve given you my youth, and you’ve given me adventure. I’m leaving you with two of our sons and all our grandchildren. You are taking a piece of my heart and soul. I will remember you daily with amazement and intrigue,” Cook wrote in the book’s last chapter.

“Though I have put pen to paper, you and I both know the words only go so far in describing the decades we have spent together. Some things, despite my best effort, were simply indescribable. Farewell, my friend.”