Immune cells can take on healing abilities to repair nerve fibers: Study

Discovery could lead to new treatments for diseases like MS

Written by |

When given a specific set of chemical cues, immune cells called neutrophils are able to take on healing abilities that allow them to help repair damaged nerve fibers, a study by U.S. researchers found.

The researchers hope to build on this discovery to create new treatments for multiple sclerosis (MS) and other neurological disorders that are marked by nerve damage.

“Our new study shows that patients’ own cells can likely be used to deliver safe and effective treatments for these devastating conditions,” Andrew Jerome, PhD, a co-first author of the study at The Ohio State University, said in a press release.

Benjamin Segal, MD, a professor at Ohio State and senior study author, added that the ultimate goal of this project “is to develop treatments using these special cells, to reverse damage in the optic nerve, brain, and spinal cord, thereby restoring lost neurological functions.”

The study, “Cytokine polarized, alternatively activated bone marrow neutrophils drive axon regeneration,” was published in Nature Immunology.

Neutrophils found to take on healing abilities when given chemical cues

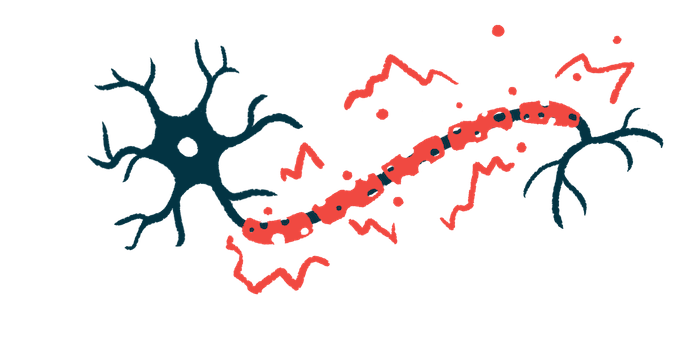

MS is marked by inflammation that damages nerve fibers throughout the central nervous system, or CNS, which comprises the brain and spinal cord, as well as the optic nerves — the nerves that connect the eyes to the brain. Nerve fibers, also known as axons, generally aren’t very good at repairing themselves, so when they become damaged in neurological disorders like MS, the effects usually are permanent.

“Dying nerve cells are typically not replaced, and damaged nerve fibers do not normally regrow, leading to permanent neurological disabilities,” Segal said.

Neutrophils are a type of immune cell that mostly are known for acting as the body’s own first responders. Specifically, when there’s an injury or infection, neutrophils are usually the first immune cell to rush onto the scene.

While all neutrophils share certain key cellular features that define their identity, modern research is continuously uncovering many different subtypes of neutrophils that have specific, hyper-specialized abilities.

In this study, the team of scientists reported on the discovery of one such subtype of neutrophil. The team found that when neutrophils taken from the bone marrow are programmed with a particular set of signaling molecules called cytokines — in particular two cytokines called interleukin-4 (IL-4) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) — they start to manufacture molecules called growth factors that can help support axon regeneration.

In further experiments, first using cells in dishes and then in mice with spinal cord injuries, the researchers showed that this reprogrammed subset of neutrophils was able to promote the growth of new, healthy axons when nerve fibers were injured.

“Adoptive transfer of IL-4/G-CSF-polarized bone marrow neutrophils into experimental models of CNS injury triggered substantial axon regeneration within the optic nerve and spinal cord,” the scientists wrote.

The researchers also showed these neutrophils could be generated using cell samples from human patients, and in lab experiments, the human neutrophils showed the same ability to repair nerve fibers that had been seen in mouse studies.

With the success of these lab experiments, our focus now shifts to bringing these new cell therapy treatments to the patients who need them. … We believe these cells can be extracted from a patient, stimulated and grown to large numbers in the lab and reinfused at the site of injury or disease to regrow brain and spinal nerve fibers.

The researchers now are hoping to expand these findings about the healing abilities of this subset of neutrophils to develop a treatment that can be used in people with diseases like MS. The team is already conducting further preclinical tests, aiming to figure out optimal conditions for such a treatment.

“With the success of these lab experiments, our focus now shifts to bringing these new cell therapy treatments to the patients who need them,” said Andrew Sas, MD, PhD, assistant professor at Ohio State and co-first author of the study.

“We believe these cells can be extracted from a patient, stimulated and grown to large numbers in the lab and reinfused at the site of injury or disease to regrow brain and spinal nerve fibers,” Sas said.