ECTRIMS, EBMT suggest stem cell transplant for some with RRMS

Younger patients early in disease course seen benefiting

Written by |

Stem cell transplant can be considered a viable treatment option for people with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) who are young, early in the disease course, do not have other major health issues, and have failed to respond to available medications, according to a new set of recommendations.

The procedure is generally not advisable as a first-line treatment or for people with progressive MS who are older or have many other health problems, said the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) and the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT).

The recommendations were detailed in a paper, “Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treatment of multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder — recommendations from ECTRIMS and the EBMT,” published in Nature Reviews Neurology.

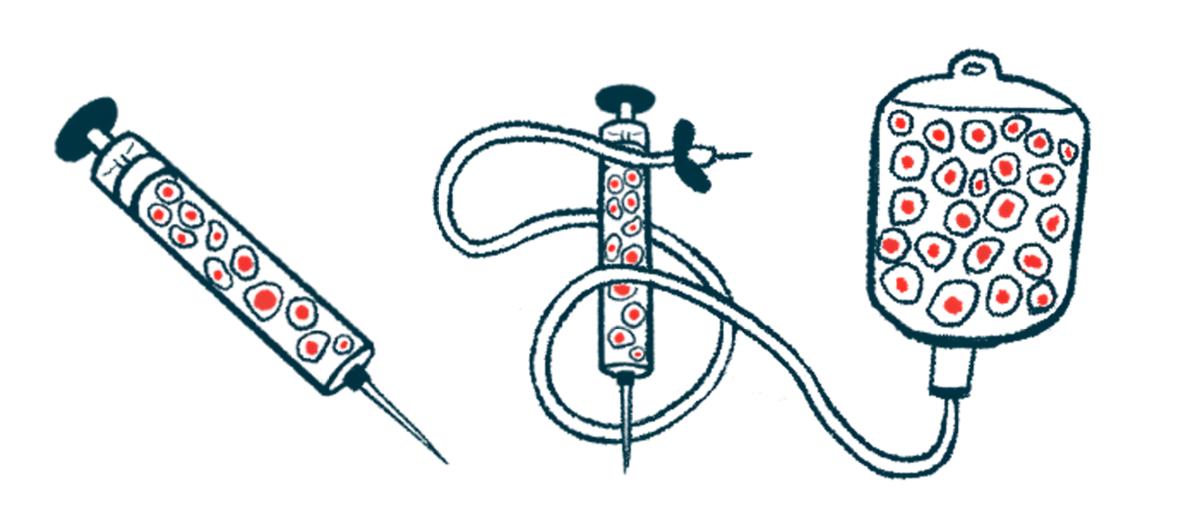

Stem cell transplant, known as autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or aHSCT, is an intensive procedure that basically aims to reset a person’s immune system.

In aHSCT, stem cells that are responsible for making new immune cells are collected from a patient, who then undergoes an intensive round of chemotherapy that aims to wipe out the person’s existing immune system before the collected stem cells are infused back and travel to the bone marrow to grow a new immune system.

ECTRIMS, EBMT team of experts

The idea behind aHSCT in MS is to help reduce the brain and spinal cord inflammation that drives the disease. The use of this procedure in MS patients has been controversial, because it’s very intensive and carries notable safety risks.

There’s been debate as to how to prioritize the use of aHSCT as opposed to disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) that are very effective at reducing disease activity and slowing the progression of MS.

ECTRIMS and the EBMT convened an international team of experts to review the available data on aHSCT in MS, offering guidance for when the procedure should and should not be used.

The researchers found substantial evidence that aHSCT can be a powerful tool to limit MS disease activity, at least in some cases. In particular, there’s a fair amount of data supporting aHSCT in people with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), they said.

“Uncontrolled cohort studies and meta-analyses have shown that among people with relapsing-remitting MS in whom standard treatment has failed, AHSCT has high effectiveness with acceptable safety,” the researchers wrote.

Data show that outcomes from aHSCT tend to be best in patients who are younger than 45, have been living with MS for less than a decade, do not have problems with cognition or walking, and have highly active disease. Outcomes are generally less favorable for patients older than 55 who have been living with MS longer than 20 years or have cognitive or walking impairment.

Based on these data, the researchers said that aHSCT may be recommended in MS patients who are younger and less disabled, and whose disease is highly aggressive. For people with RRMS, aHSCT should only be offered to patients who have failed to respond adequately to a high-efficacy DMT and whose disease is rapidly progressing. aHSCT as a first-line treatment should only be offered in the context of studies like clinical trials, they said.

The team noted that several studies are ongoing to directly compare aHSCT against high-efficacy DMTs in people with RRMS. Results from these studies are expected over the next five years or so, and will likely help inform future recommendations.

“AHSCT should be offered to appropriate candidates, normally after failure of high-efficacy DMT but within the window of opportunity before the development of irreversible disability,” the scientists wrote. “More evidence to inform the optimal positioning of AHSCT in MS care is awaited from ongoing [clinical trials] in which AHSCT is being compared with high-efficacy DMTs in relapsing–remitting MS.”

The researchers noted that there’s not much data supporting the efficacy of aHSCT in progressive forms of MS, which are marked by gradual worsening of symptoms over time. Still, they said, aHSCT might be considered for some people in the early stages of progressive MS who have evidence of substantial inflammatory activity and rapid disability worsening despite treatment.

In addition to considering MS disease activity, doctors should weigh the safety risks of aHSCT must also be considered when deciding if patients are good candidates for the procedure, the researchers said.

Because aHSCT is highly intensive, it’s generally not recommended for patients who have active infections or multiple other health issues. And because aHSCT works to reset the immune system, patients who’ve undergone the procedure need to get all recommended vaccines afterward, as vaccines given prior to the procedure will likely be rendered ineffective, the researchers said.

Because aHSCT can affect fertility, the risks should be discussed in depth prior to a procedure, and patients should be offered personalized care to manage their reproductive choices.