2 researchers win Breakthrough Prize for MS discoveries

Work related to B-cells and Epstein-Barr awarded $3 million each

Written by |

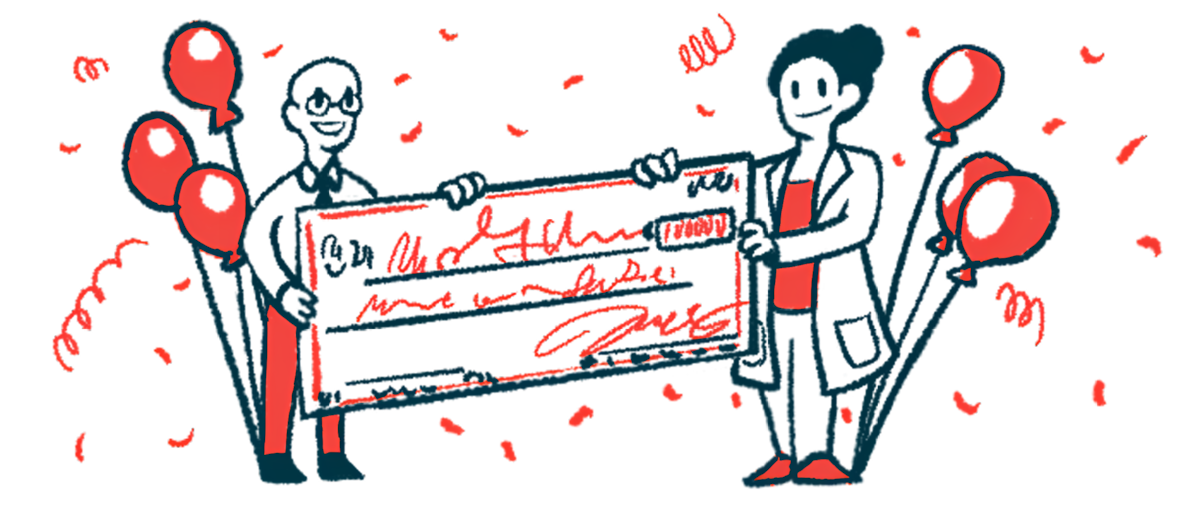

A pair of scientists have been awarded a 2025 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for their work uncovering factors that give rise to multiple sclerosis (MS), paving the way for new therapeutic developments.

Sometimes referred to as the “Oscars of Science,” Breakthrough Prizes are given each year to scientists who drive innovative discoveries in the life sciences, physics, and mathematics. This year, six prizes of $3 million each were awarded.

The two MS researchers — Stephen Hauser, MD, and Alberto Ascherio, MD, doctor of public health — will share one of the three life sciences awards.

“This year’s Breakthrough Prize laureates have made amazing strides — including treatments for major diseases affecting millions of people worldwide — showing once again the transformative power of curiosity-driven basic science,” Priscilla Chan, MD, and Mark Zuckerberg, two of the prize’s founding sponsors, said in a Breakthrough Prize Foundation press release.

MS is an autoimmune condition wherein the immune system mistakenly attacks myelin, the fatty substance that surrounds and protects nerve cells. These inflammatory attacks produce areas of damage called lesions in the brain and spinal cord.

Hauser, a professor of neurology and director of the Weill Institute for Neurosciences at the University of California, San Francisco, earned the award for identifying that immune B-cells are key drivers of these attacks.

Historically, it was believed that MS was driven mainly by a class of immune cells called T-cells, but Hauser’s work in animal models and MS patient tissue showed that B-cells also played a central role.

This discovery led to the development of B-cell-targeted therapies now widely used to treat MS. This class of therapies includes Genentech’s Ocrevus (ocrelizumab), Novartis’ Kesimpta (ofatumumab), and TG Therapeutics’ Briumvi (ublituximab), all of which are antibody-based therapies designed to deplete B-cells.

These treatments have substantially altered the outlook for MS patients, according to the scientist.

“In the past, newly diagnosed patients would be told that they may require a cane or wheelchair within 15 years,” Hauser said in a university news article. “Today, our data indicate that many new patients can expect lives free from disability.”

The scientist acknowledged that many others contributed to the discoveries that led to B-cell-depleting therapies for MS, particularly the patients who participated in clinical trials.

“Without them, this breakthrough would not have been possible,” Hauser said.

Hauser now continues with research to help improve outcomes for people with MS, including work to discover genes linked to the disease. He hopes that a recently discovered genetic region could lead to new therapeutic approaches for people with progressive forms of MS who don’t respond as well to B-cell therapies.

“I have never been more optimistic for the future: what’s in store for our patients today, as well as those developing MS in the future, who may soon be diagnosed — and treated — even before they experience their first symptom,” Hauser said.

Discoveries about the Epstein-Barr virus

For his part, Ascherio, a professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School, was involved in the historic discovery that a past infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a leading cause of MS.

Ascherio’s career has been inspired by a drive to identify the root cause of diseases to prevent them from happening.

“You realize that if you don’t prevent diseases and you don’t address the causes of disease, then people will keep getting sick,” Ascherio said in a Harvard news article. “So, I thought, can we go more to the root — to find the cause of the disease and intervene there?”

Most adults have been infected with EBV, even if they aren’t aware of it. After the initial infection, the virus is latent within the body for the rest of a person’s life. Scientists had believed for many decades that MS could be caused by a viral infection such as EBV, but there hadn’t been sufficient data to establish that.

In a landmark study involving more than 10 million members of the U.S. military, Ascherio and colleagues found that EBV infection raised the risk of developing MS later in life by 32 times.

“It’s virtually a consensus now that EBV is the leading cause of MS,” Ascherio said.

That has led to the work on developing therapies that target EBV as a way to treat MS. Efforts are also underway to develop vaccines for preventing EBV infection.

Meanwhile, Ascherio and colleagues are continuing to investigate the mechanistic link between the common virus and MS as a way to better understand which infected people will ultimately develop the neurodegenerative disease. They’re also trying to understand whether viral infections play a role in other neurodegenerative conditions.