FAQs about rituximab in MS

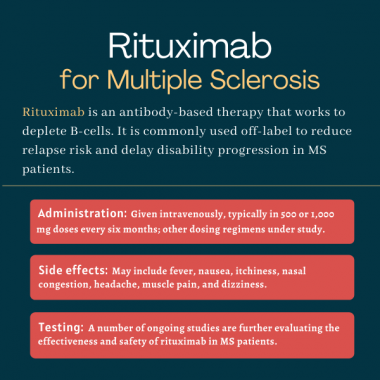

Rituximab is an antibody therapy that is not approved for MS but is sometimes used off-label in people with the condition. It works by killing B-cells, a type of immune cell that plays a central role in MS-driving inflammation. By destroying these cells, rituximab ultimately can reduce inflammation and nervous system damage in MS.

Rituximab is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat MS, and it is unknown when or if the FDA will give the medication such approval. Larger Phase 3 trials demonstrating the therapy’s safety and effectiveness in MS would be needed before rituximab could gain approval in the U.S.

Use of Rituximab during pregnancy may result in abnormally low levels of B-cells in newborn babies, which can increase the risk of serious infections. According to the labels of rituximab-based products, which are approved for indications other than MS, rituximab should only be taken during pregnancy if the potential benefits outweigh the risks; these benefits and risks should be discussed in detail between patients and their healthcare teams.

A significant reduction in the number of inflammatory brain lesions was evident with rituximab treatment as soon as 12 weeks (about three months) in the HERMES clinical trial, which compared the therapy against a placebo in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. A difference in relapse rates was evident by 24 weeks, or about six months.

Clinical trials in MS patients have not reported weight gain as a medication side effect, although weight loss was commonly noted when rituximab was used for other indications. Hair loss has not been reported as a side effect of rituximab in clinical trials. Patients who experience unanticipated effects after starting on rituximab treatment are advised to discuss these issues with their healthcare team.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by