Catching the Flu Can Trigger an MS Relapse by Activating Glial Cells, Study Suggests

Written by |

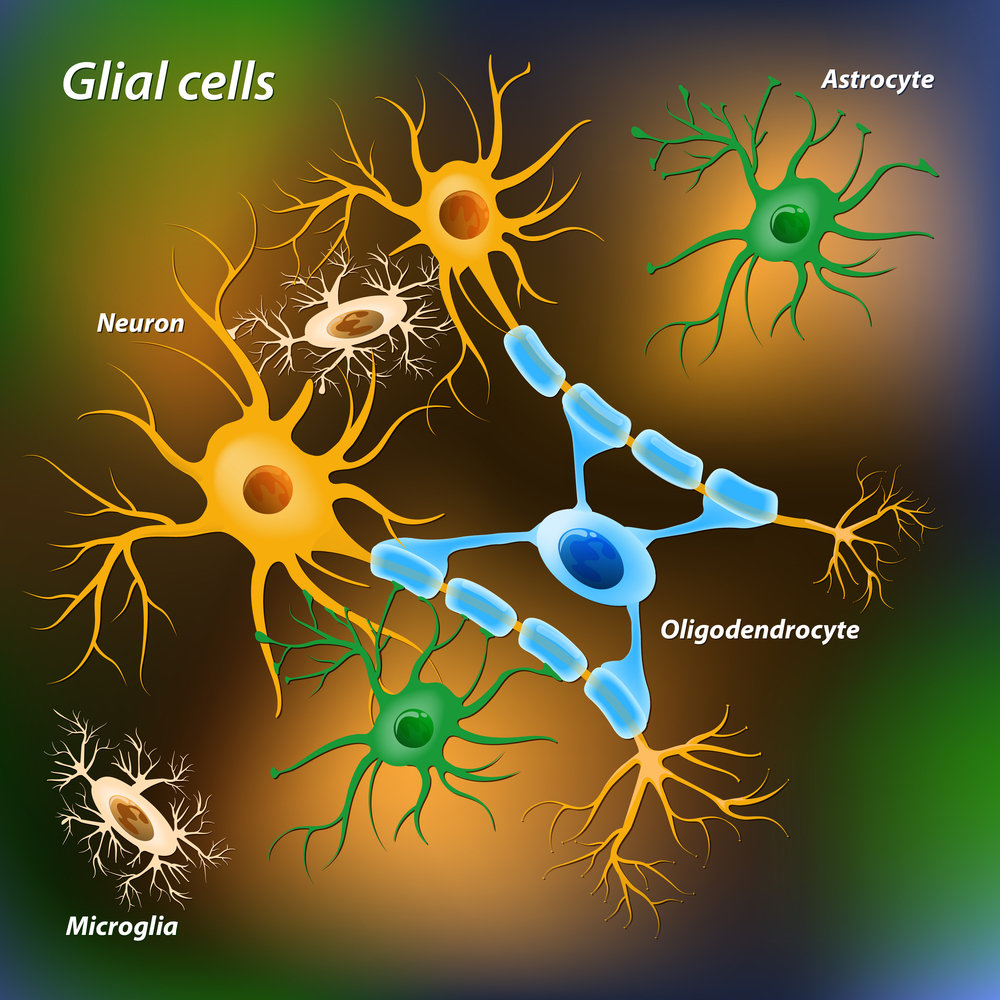

Coming down with the flu can provoke relapses in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients by activating glial cells that surround and protect nerve cells. In a study in mice, scientists found that activated glial cells increase the levels of a chemical messenger in the brain that, in turn, triggers an immune reaction and, potentially, autoimmune attacks.

The study, “Influenza infection triggers disease in a genetic model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,” was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The flu is caused by the human influenza virus and, despite being unpleasant, usually resolves itself within days. However, for people with MS and other neurological conditions, the flu can lead to disease relapse.

Researchers at the University of Illinois investigated what happens in the brain of MS patients during upper-respiratory viral infections, such as the flu.

“We know that when MS patients get upper respiratory infections, they’re at risk for relapse, but how that happens is not completely understood,” Andrew Steelman, an assistant professor at the university and the study’s senior author, said in a press release. “A huge question is what causes relapse, and why immune cells all of a sudden want to go to the brain. Why don’t they go to the toe?”

The team used a mouse model characterized by autoimmune responses within the brain and spinal cord — the type of deregulated immune responses seen in MS patients. Researchers infected the animals with a version of human influenza virus adapted to mice, and looked at changes that occurred in the animal’s central nervous system.

While the virus was never detected in the animals’ brains, upon infection some of the mice developed MS-like symptoms.

“If you look at a population of MS patients that have symptoms of upper respiratory disease, between 27 and 42 percent will relapse within the first week or two,” Steelman said. “That’s actually the same incidence and timeframe we saw in our infected mice, although we thought it would be much higher given that most of the immune cells in this mouse strain are capable of attacking the brain.”

The team then investigated how a peripheral influenza infection could contribute to disease onset. They infected a wild-type (normal) strain of mice with the flu virus and looked at alterations in the brain and spinal cord.

Scientists found that infection increased the activation of glial cells in the mice’s brains. Moreover, it induced infiltration of several immune cells — T-cells, monocytes and neutrophils — into the brain within eight hours of infection.

Glial cells surround neurons and provide support, and for this reason are known as the glue that holds nerve cells in place. Researchers here showed they have wider function, and can actually summon immune cells to the brain.

“When glia become activated, you start to see trafficking of immune cells from the blood to the brain. We think that, at least for MS patients, when glia become activated this is one of the initial triggers that causes immune cells to traffic to the brain. Once there, the immune cells attack myelin, the fatty sheaths surrounding axons, causing neurologic dysfunction,” Steelman said.

The way glial cells induce immune cells into the brain is via a particular chemical messenger (chemokine), called CXCL5. In fact, previous studies reported that the levels of this particular chemokine are increased in the cerebral spinal fluid of human MS patients during relapse. The scientists also detected higher levels of CXCL5 in the brain of mice infected with the flu virus.

Overall, these findings suggest that the chemokine CXCL5 plays a key role in mediating an autoimmune attack in MS, and might be explored for therapeutic potential.

“MS patients have one or two relapses a year; it’s thought that these relapses contribute to the progression of the disease,” Steelman concluded. “If we can pinpoint what’s driving environmental factors such as infection to cause relapse, then maybe we can intervene when the patient has signs of sickness, like runny nose or fever. If we could inhibit relapse by 50 percent, we could theoretically prolong the time it takes for the patient to experience continual loss of function and dramatic disability.”