#MSParis2017 – Types of Brain and Spinal Cord Lesions Help Determine if MS Develops, Study Reports

Written by |

The types of brain and spinal cord inflammation patches that occur in a precursor condition to multiple sclerosis help determine whether a person develops MS in the next 15 years, a British neurologist reported today.

Wallace J. Brownlee of the University College London Institute of Neurology made the observation in a presentation at the 7th Joint ECTRIMS-ACTRIMS Meeting in Paris.

He was referring to inflammation patches known as brain and spinal cord lesions in people who have clinically isolated syndrome, or CIS. Doctors classify a person as having CIS after they experience their first episode of neurologic symptoms stemming from inflammation or loss of the protective myelin coating around nerve cells. CIS often progresses to secondary progressive MS.

The study’s findings could help doctors do a better job of predicting whether CIS will turn into MS, Brownlee said.

The Paris conference, which started Oct. 25 and runs through Oct. 28, has attracted more than 9,000 MS scientists, doctors and others.

Brownlee’s study is one of the first to examine how early signs of CIS may influence the disease’s progression. His presentation was titled “New spinal cord and infratentorial lesions in early relapse-onset MS are predictive of secondary progressive disease course after 15 years.”

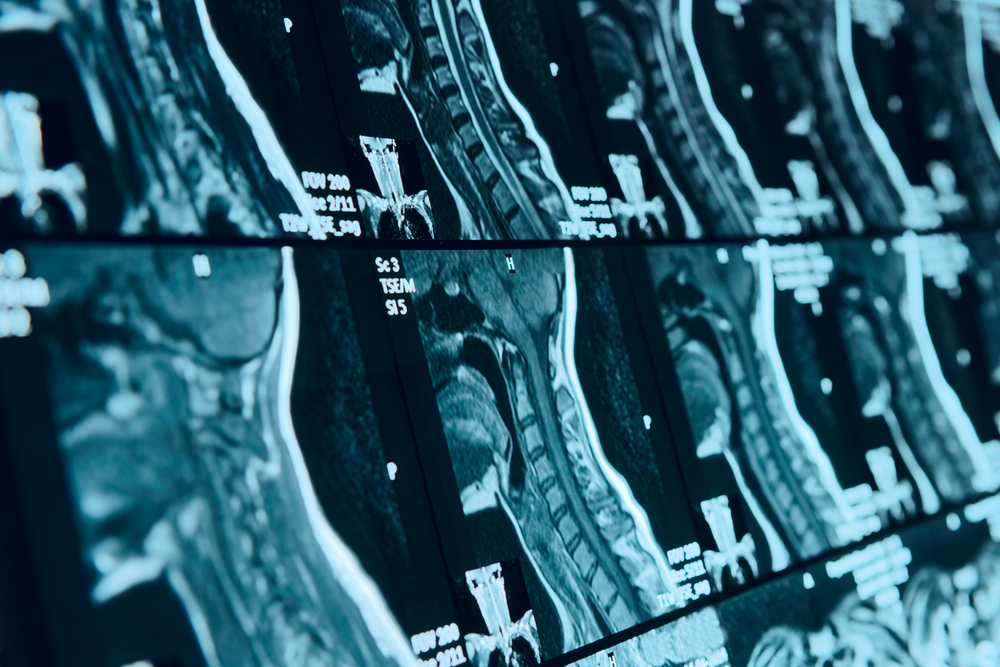

The study involved 164 CIS patients. Researchers used magnetic resonance imaging to look at their brains and spinal cords just after they received their diagnosis. Among them, 136 had follow-up scans after a year, and 121 follow-up scans after three years.

Brownlee’s team followed the patients for 15 years to see whether the types of lesions that CIS patients had when they received their diagnosis, and at one and three years, were associated with them developing relapsing MS, and later secondary progressive MS, or SPMS.

A key finding was that people with CIS who had more spinal cord lesions were at 4 1/2 times more likely to develop SPMS 15 years later than people with fewer lesions.

The research team also said a type of lesion known as a gadolinium-enhancing lesion increased by 1.7 times the chance that a CIS patient would develop SPMS, compared with those who had no such lesions. Gadolinium-enhancing lesions indicate that inflammation is ongoing.

At the start of the study, CIS patients who developed SPMS later “had more spinal lesions and showed a trend for more gadolinium-enhancing lesions,” Brownlee said.

Another finding was that new lesions in the spinal cord or lower parts of the brain a year after a CIS diagnosis increased by 5.7 to seven times the risk that a patient would develop SPMS within 15 years. Gadolinium-enhancing lesions doubled the risk.

The risk that new lesions would lead to SPMS soared three years after a CIS diagnosis. New spinal cord lesions made it 39 times more likely a CIS patient would develop SPMS, compared with a patient with no new lesions. CIS patients with both new spinal cord and new lower brain lesions at three years were at 53 percent higher risk of ending up with SPMS within 15 years.

In contrast, people with no new lesions in their spinal cord and lower parts of the brain had only a 0.9 percent risk of developing SPMS 15 years later.

“Patients who remained CIS at 15 years had mostly normal [MRI] scans,” Brownlee said.

The research team also examined lesions in the upper part of CIS patients’ brains — above the cerebellum — along with their brain volume and cervical spinal cord cross-sectional area. They found no link between changes in these measurements after one and three years and the risk of a CIS patient developing SPMS.

The bottom line was that an accumulation of lesions in the spinal cord and lower brain regions appears to drive disease progression — a point that physicians should consider when trying to predict whether their patients will develop MS, the team said.

“Brain atrophy did not appear to differ greatly between the groups, but spinal cord atrophy was more severe,” Brownlee added, emphasizing the need for spinal cord MRIs in CIS patients.