Easing Blood Flow in Neck Reduces Headaches, Fatigue in Certain MS Patients, Study Shows

Written by |

Removing obstructions in large neck veins reduced multiple sclerosis patients’ headaches for several years, British and Italian researchers have demonstrated.

The magnitude and duration of the effect differed among patients with different types of MS, however.

Researchers also found that the treatment reduced fatigue, particularly in relapsing-remitting (RR) MS patients. But fatigue reductions waned much quicker than headache reductions, and were not as robust, the study in the journal PLOS ONE showed.

This prompted the team to suggest that the method used to remove neck vein obstructions — balloon angioplasty — may be useful for treating persistent headaches in MS patients with obstructed veins. The researchers were from Leeds Beckett University in the U.K. and the Catania University Hospital in Italy.

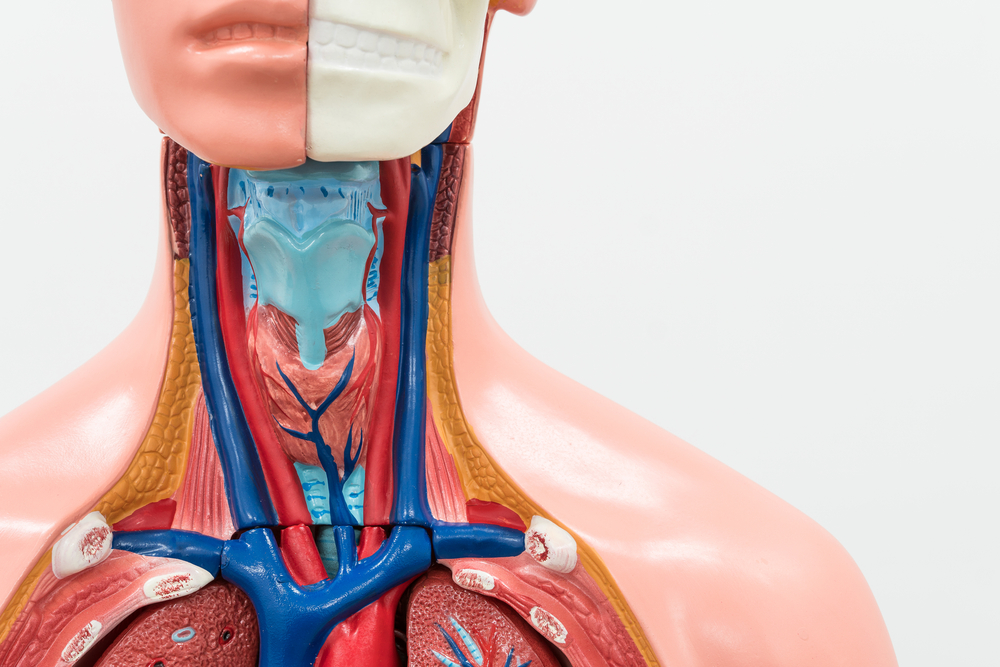

It was only about 10 years ago that researchers suggested that many MS patients have obstructed blood flow from the brain. The condition, called chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency, can be treated by inserting a catheter into the veins, draining the brain and spinal cord. The catheter carries a balloon, which is inflated to open up the blocked blood vessels.

The method is called balloon angioplasty. Despite its common use, it is considered controversial, researchers said — partly because studies are not in agreement about its benefits.

To examine whether the treatment could affect headaches and fatigue in MS patients, researchers recruited 286 MS patients with large neck vein obstruction. They titled their study “Mid-term sustained relief from headaches after balloon angioplasty of the internal jugular veins in patients with multiple sclerosis.”

The study group was composed of 175 RRMS patients, 75 secondary progressive MS (SPMS) patients, and 36 primary progressive MS (PPMS) patients. Among them, 113 had headaches and 277 experienced fatigue. The two groups were not mutually exclusive, as some patients had both headaches and fatigue.

The team measured improvement using the Migraine Disability Assessment tool and the Fatigue Severity Scale, before, and on two occasions after, balloon angioplasty.

Researchers also checked if the blood vessels — the internal jugular veins — were still open at one, six, and 12 months after the procedure and yearly thereafter.

The treatment reduced headaches and fatigue at three months in all the patients. But the result was not statistically significant for headaches in PPMS patients, likely because of the small number in the group. Reductions in the number of headaches were similar in SPMS and PPMS patients. The most reductions occurred in RRMS patients.

Headache reductions held in RRMS patients over the long term. But at an average follow-up of roughly 3 1/2 years, the number was slightly higher than recorded earlier.

A similar situation was seen in SPMS and PPMS patients, but again the result was not significant in PPMS.

Meanwhile, only RRMS patients’ fatigue continued to be lower at long-term follow-up, although it had increased from the early follow-up. In SPMS and PPMS patients, fatigue scores were lower than initial levels, but the difference was not significant.

Researchers linked improvements in headaches and fatigue with changes in blood flow in the internal jugular veins.

The data suggested that balloon angioplasty may be a valuable way to reduce headaches, and possibly also fatigue, in MS patients with obstructed neck veins, researchers concluded.