Biomarker in Cerebrospinal Fluid Seen to Predict MS Progression in Study

Written by |

A potential biomarker — the ratio of antibody proteins in cerebrospinal fluid at the time of diagnosis — was seen to predict which multiple sclerosis patients will progress into full-blow disability some five years after being diagnosed in a new study.

If confirmed in larger clinical studies, this biomarker could to help to identify those MS patients who have poor prognosis and might benefit from early and more aggressive treatment, and possibly spare those with a better prognosis treatments known to have potentially serious side effects.

The study “Cerebrospinal fluid immunoglobulin light chain ratios predict disease progression in multiple sclerosis” was published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

MS severity and progression varies widely between patients; some suffer multiple attacks and move quickly to marked disability, while others show only a first clinical episode of the disease — known as clinically isolated syndrome.

“Although there are now a wide range of therapies available for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, the specific choice of treatment in any individual patient is not made in a very evidence-based way,” Michael Douglas, honorary professor at the University of Birmingham and the study’s lead author, said in a university press release.

Finding long-term prognostic markers would help guide the therapeutic choices, but currently “we do not have reliable long-term outcome predictors for individual patients to guide their choice between more potent therapies with potentially greater side effects, and more gentle therapies which may not fully control the condition,” Douglas said.

Biomarkers that might “predict future risk of disability” are for this reason important — they could work “to ensure that individual patients receive the right treatment at the right time,” he added.

The researchers asked whether the cerebrospinal fluid — a liquid that flows within the brain and spinal cord — could hold the key to predicting MS progression.

They analyzed the spinal fluid from MS patients undergoing an elective lumbar puncture at two timepoints: when they were diagnosed and five years later. They then quantified the amount of immune B-cells found; these cells are responsible for producing antibodies.

The analysis included individuals diagnosed with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS, 43 patients), those with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS, 50 patients), primary progressive MS (PPMS, 20 patients), and individuals with other neurological disease — both inflammatory (23 patients) and non-inflammatory (114 patients) — who served as controls.

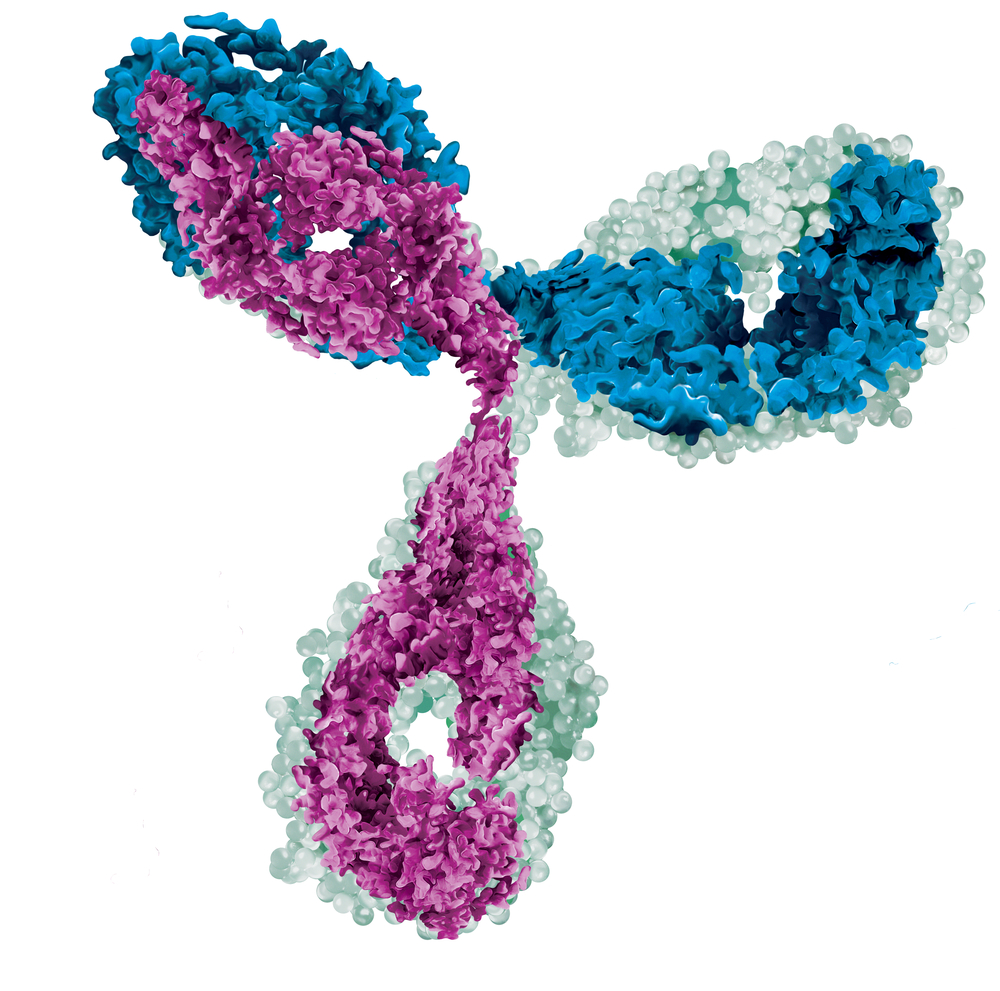

Results revealed a highly unusual pattern in the behavior of B-cells, shown by differences in the amount of antibodies produced between patients and both control groups. Researchers measured specifically a group of proteins — called kappa and lambda light chains — that are assembled together with other proteins to produce antibodies.

All MS patients and individuals with CIS had a much higher ratio of the antibodies’ light chains compared to controls.

Most important, researchers found that the kappa/lambda ratio determined at the time of diagnosis could predict MS disease progression at five years, measured via the expanded disability status scale (EDSS; the higher the score, the greater the disability).

Patients with a high ratio (above 10) had a significantly lower EDSS at five-year follow-up, while those with a low ratio (below 10) accumulated greater disability.

“Collectively, these data show that the CSF [cerebrospinal fluid] kappa/lambda FLC [free light chain] ratio at the time of diagnosis is predictive of the subsequent MS disease course,” the researchers wrote.

“The unusual pattern of antibody suggests a very distinct immune response early in the disease. We are hoping to identify the target of this immune response,” said John Curnow, a study co-lead author.

“Alongside improving our fundamental understanding of MS, this presents the opportunity to identify patients who are at higher risk of developing disability and may need more aggressive treatment. Similarly, it may be possible to identify patients at lower risk, who may be able to manage their condition more conservatively,” Curnow added.

While additional studies with larger patient groups are required to confirm these findings, the results point to a potential new prognostic marker for disability and early therapeutic intervention.

“If our findings are confirmed, then we would have a relatively simple test that could be used at diagnosis to help identify patients with a poor prognosis. This will enable clinicians to justify the use of highly effective therapies, which could potentially improve the long-term outcomes for these patients,” Curnow concluded.