Antibody Targeting Clotting Factor Seen to Lessen Inflammation, Nerve Cell Damage in MS Model

Written by |

An antibody that blocks a blood-clotting factor from leaking into the brain was seen to lessen neuroinflammation and nerve cell damage in mouse models of multiple sclerosis (MS) and Alzheimer’s disease.

Scientists developed an antibody that selectively inhibits the inflammation-triggering capacity of fibrin in the brain — a potential way of treating neurodegenerative conditions — and without limiting its essential work in helping blood to clot.

Fibrin-driven neurodegeneration may be a common mechanism in many neurological diseases, including MS, and targeting it with immunotherapy may be a new way of preventing such damage, the researchers say.

Their study, “Fibrin-targeting immunotherapy protects against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration,” was published in the journal Nature Immunology.

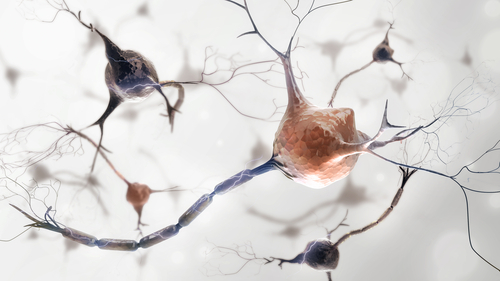

Chronic activation of the immune response in the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) is common to many neurological diseases. Prior research indicates that chronic neuroinflammation and oxidative injury (caused by toxic reactive oxygen species) are key drivers of neurodegeneration in both relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) and progressive MS.

But little is known about the signals underlying the aggressive and abnormal immune activation that triggers nerve cell damage.

In several neurological disorders, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) — a protective membrane that limits molecules which can move from the blood to the brain — becomes more permeable.

Normally, the BBB only allows the passage of small molecules, fat-soluble molecules, and some gases from the bloodstream into the brain. In many neurological conditions, however, this barrier is disrupted and proteins like fibrin, a key blood-clotting factor, enter.

From prior studies, fibrin is known to trigger inflammation within the brain, and it has been detected in active and chronic brain lesions of MS patients. For this reason, a team led by researchers at the Gladstone Institutes wondered if fibrin could be the signal that induces neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in MS.

Researchers have largely avoided targeting fibrin as a therapeutic approach due to concerns that such efforts would limit the essential blood clotting this protein regulates. This study suggests a possible solution to this problem.

Its scientists designed an antibody that selectively targets a small portion of the fibrin protein known to activate the immune response, leaving the protein region responsible for clotting unaffected.

Using mouse models of MS and Alzheimer’s, researchers saw that treatment with this antibody reduced the activation of cellular pathways that lead to inflammation and oxidative stress, two potential sources of toxic chemicals that may contribute to nerve cell death.

Moreover, the anti-fibrin antibody did not interfere with the protein’s blood clotting capacity.

“We have developed a monoclonal antibody to target a major culprit in the blood that damages the brain. Fibrin-targeting immunotherapy could protect the brain from the toxic effects of blood leakage and may also have beneficial effects in other organs affected by inflammatory conditions with vascular damage,” Katerina Akassoglou, PhD, director at the Gladstone Institutes, a professor at the University of California San Francisco, and the study’s senior author said in a press release.

Importantly, in the MS mouse models, the immunotherapy reduced the activation and accumulation of inflammatory cells in the spinal cord, and lessened nerve cell damage and demyelination (loss of myelin) of nerve fibers, a hallmark of MS.

“Our study supports that vascular damage leading to immune-driven neurodegeneration may be a common thread between diseases of different etiologies with blood-brain barrier leaks,” Akassoglou said. “Targeting fibrin with immunotherapy is a new approach that could be used to test the therapeutic benefits of suppressing this pathogenic mechanism in multiple disease contexts.”

The researchers next plan to develop an antibody that can be used in patients. But Akassoglou cautions that clinical studies testing such this future antibody will need to closely monitor both patients’ immune system and blood clotting abilities.