Does the myelin sheath play a role in MS?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurodegenerative disease in which the body’s immune system attacks the myelin sheath, a substance that protects nerve cells and helps them efficiently send the electrical signals necessary for proper neurological function.

The loss of myelin, or demyelination, that results from these inflammatory attacks ultimately leads to damage and dysfunction of the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves.

What is the myelin sheath?

The CNS is comprised of several components that are vital to its function, including:

- nerve cells, or neurons: cells that send and receive the signals that give rise to movements, sensations, thoughts, and emotions

- myelin: a coating around neurons that protects them and helps them send signals efficiently

- glial cells: cells that support neuron function

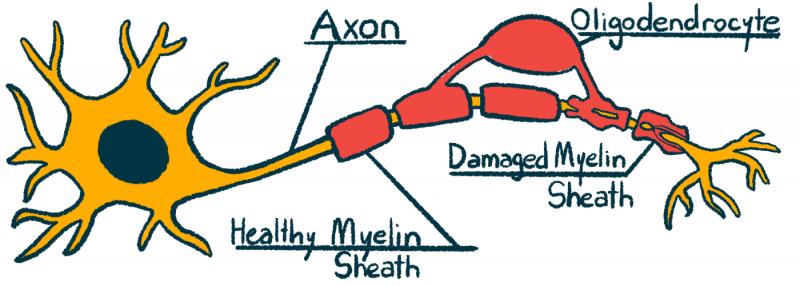

When a neuron “fires,” it sends an electrical current from one end of the cell to the other via a long, fiber-like projection called an axon. From there, the neuron passes signals on to the next cell by releasing chemical messengers called neurotransmitters in a process known as neurotransmission.

Myelin, mainly made of fatty molecules and specialized proteins, surrounds the axons of many neurons in the CNS. Along the length of an axon, there are regions densely wrapped in myelin, interspersed with areas of little to no myelin, called nodes of Ranvier.

Among the various types of glial cells are oligodendrocytes, which are involved in creating and maintaining the myelin sheath in the CNS.

How does the myelin sheath function?

Often, nerve fibers need to send electrical signals over long distances to reach different parts of the CNS. Myelin plays a key role in enabling these signals to be transmitted efficiently and preserving their strength as they travel that distance.

It acts somewhat like the rubber insulation that coats a metal wire. Just as the rubber helps direct electricity through the wire and prevents the electrical signal from leaking out before it reaches its destination, myelin helps insulate and direct electrical signals down an axon.

Without myelin, an electrical signal travels relatively slowly and continuously down the entire length of an axon. By contrast, when an axon is myelinated, the signal can “skip” across segments of dense myelin quickly, essentially jumping between the nodes of Ranvier to travel faster. The signal is recharged at these nodes to maintain its original strength.

Historically, most research about myelin was focused on its role in speeding neuronal signaling, but recent research has demonstrated that myelin also has several other functions:

- Energetic and metabolic support: Myelin connects axons to oligodendrocytes, which provide neurons with molecules needed to produce cellular energy, as well as factors that support neuronal nutrition and survival.

- Water and salt balance regulation: Myelin helps regulate levels of water and salts in neurons, which maintains the chemical balance required for efficient signaling.

- Plasticity: Myelin can remodel itself to fine-tune neuronal function throughout life in response to the body’s needs. For example, by adjusting its thickness, myelin can alter the speed of nerve signals, coordinating them so that signals from several parts of the CNS all reach one brain area at the same time. This process, known as plasticity, is essential for complex processes, such as learning and memory.

How is the myelin sheath linked to MS?

In MS, the immune system launches inflammatory attacks that target the myelin sheath, leading to its deterioration. This demyelination leaves axons unprotected, making them vulnerable to damage.

Over time, MS lesions — areas where tissue is damaged and scarred — form in the CNS. These lesions, visible on MRI scans, give MS its name: the disease is characterized by “multiple” areas of scarring, or “sclerosis.”

Demyelination and nerve damage disrupt efficient electrical signaling between neurons. In turn, impaired neural activity is responsible for most symptoms of MS. In general, a person’s specific symptoms will depend on which parts of the CNS are impacted.

There are a number of demyelinating disorders that affect the CNS, but MS is one of the most common.

What causes damage to the myelin sheath?

Scientists don’t know what initially triggers the self-directed immune attacks that drive MS. Many interconnecting risk factors — including genetics, lifestyle habits, and environmental exposures — may contribute to the development of the autoimmune disease.

Several immune cell types are thought to contribute to myelin damage in MS, with T-cells and B-cells being the most extensively studied.

- T-cells have receptors that can recognize a single molecule, usually a piece of a virus or bacteria. In MS, T-cell receptors mistakenly identify components of myelin as potential threats and coordinate attacks against them.

- B-cells normally produce immune proteins called antibodies that help guide the immune system to a harmful invader. In MS, they enter the CNS and contribute to inflammation by making misguided antibodies and activating other immune cells. Antibody levels are often high in the CNS of people with MS, and measuring them in the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord can help diagnose the disease.

Accumulating research suggests that various other immune cell types may also promote MS-driving inflammation. Unusual activity in some types of glial cells — including microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells — can further exacerbate autoimmune attacks.

Does the myelin sheath regenerate?

Damaged or destroyed myelin can be repaired or replaced through a process called remyelination.

It’s thought that most remyelination happens when immature precursors, called oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), travel to areas of demyelination and develop into young myelin-producing oligodendrocytes that can wrap surviving neurons in new myelin.

Remyelination occurs to some extent naturally, but the process becomes less efficient with age. Disease-related inflammation can further interfere, and myelin repair is often incomplete in people with MS.

As such, there is interest in developing experimental MS therapies that can promote remyelination. These treatments may stimulate OPCs to increase the availability of young oligodendrocytes or target other steps in the remyelination process.

Dozens of potential remyelinating treatments have shown promise in laboratory studies, and some have yielded positive results in early MS clinical trials. However, many clinical studies have had inconclusive or poor results

Some of the potential remyelinating treatments being tested in MS clinical trials include:

- CNM-Au8

- metformin and clemastine, used alone or together

Non-drug interventions, including exercise and anti-inflammatory diets, could also promote remyelination in MS, although research in this area is still ongoing.

Several disease-modifying treatments are available to slow MS progression or reduce the risk of relapses. Some of these medications, which primarily target ongoing inflammation, may also promote myelin repair, although this is still an area of active research.

Multiple Sclerosis News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by