#CONy16: Scientists Debate MRI’s Role in MS Treatment Changes; Exclusive Interview with Prof. Xavier Montalban

Written by |

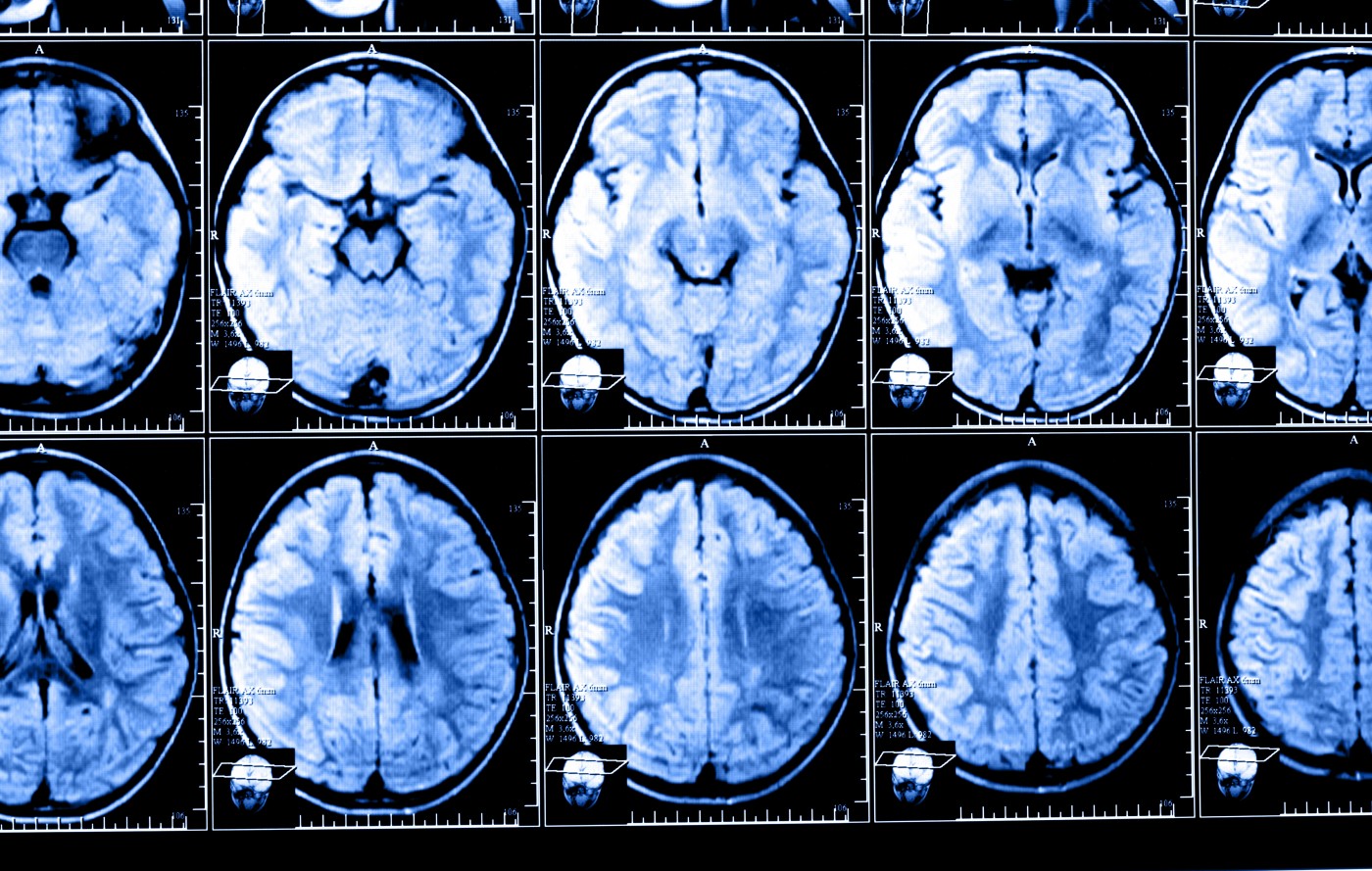

The precision of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurement has improved over the years, and now scans can identify brain damage before symptoms begin showing. Whether the presence of new or expanding lesions predict disease progression is, however, still controversial, and clinicians have no guidance when making treatment decisions about the management of potential high-risk patients.

Discussions have gone back and forth for years about using conventional and unconventional MRI techniques for both predicting disease progression and monitoring treatment response. The argument continued March 18 at the 10th World Congress on Controversies in Neurology (CONy) in Lisbon, Portugal, where Uroš Rot, from the University Medical Centre in Ljubljana, Slovenia, and Mark S. Freedman, from the University of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada, presented opposing views on the topic.

The debate at CONy, “My MRI worsened but I didn’t. Should I change my disease-modifying treatment?” was hosted by Prof. Xavier Montalban, chairman of the Department of Neurology-Neuroimmunology and director of the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia at the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona, Spain.

Rot, holding a critical position, noted that studies exploring a connection between asymptomatic lesions and both early and late disease progression pointed in different directions, with some studies showing negative results.

He argued that most of the studies showing an association between MRI findings and disease progression looked at patients receiving treatment with interferon-beta, which limited their use for patients receiving other treatments.

Freedman argued the opposite, claiming it is not possible to ignore the power of MRI and that findings from imaging that are not paralleled by symptoms are still relevant enough to be included in all current interpretations of the diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS), revised in 2010.

These criteria are based on the need to demonstrate the presence of lesions, disseminated in both space and time.

He supported his arguments by citing a recent publication by the Magnetic Resonance Imaging in MS (MAGNIMS) network that proposed an even more simplified and less ambiguous definition of the diagnostic criteria. This publication also provided clinical guidelines for how to use MRI findings in making treatment decisions.

Supporters of MRI use, including the MAGNIMS network, contend that the increasing availability of disease-modifying drugs, thought to be most effective in early disease stages, makes an early diagnosis crucial. However, these drugs can have severe side effects, and the MAGNIMS consortium also indicated that MRI is an important tool for monitoring response to treatment.

Freedman reasoned that determining tissue damage at baseline, as well as repair following treatment, might help to assess efficacy and safety of new therapies.

While the MAGNIMS publications quoted by Freedman were based on an assessment of a large body of published studies, Rot argued that the interpretation of comparative MRI data is accompanied by many caveats which need to be considered for a correct analysis of patient circumstances.

Rot said there is currently no consensus about how many new silent lesions have to appear during the first year for a correct early or late prognosis. The interferon-beta studies reported that varying numbers of new lesions predicted worse patient outcomes.

Freedman did not agree, and pointed out the MAGNIMS work built on the influential work of Prosperini, who showed that each new lesion was associated with a tenfold increased risk of being a poor responder to interferon-beta therapy. This study prompted new Canadian Treatment Optimization Recommendations, establishing cut-off values for new lesion development that should encourage a treatment switch.

To further back his case, Rot maintained that the effects of treatment with interferon-beta and glatiramer acetate are delayed. Since new lesions could arise before the drugs become effective, MRI is not an optimal tool for assessing treatment efficacy.

“MRI-only worsening does not predict disability after three years in patients treated with glatiramer acetate,” he said, and added that there is only “some evidence that MRI-only worsening indicates early unstable disease and worse late clinical outcome in IFN beta-treated MS patients.”

Rot also said studies showed that patient adherence to injectable treatment is generally low, which might further disturb the analysis of MRI findings.

Particularly unconventional MRI measures, such as brain atrophy, should not be incorporated into clinical decision making, according to Rot. On this point, the two researchers agreed, and the MAGNIMS consortium has stated that there is not enough evidence to recommend brain atrophy measures for use in clinical practice.

Rot also claimed that interpretation of MRI data is highly variable, citing a study that found between-rater variability to be high, particularly when assessing enlarging T2 lesion.

Freedman agreed that this variability is a problem, but believes that strict adherence to a standardized set of MRI acquisition sequences, which provide more accurate follow-up comparisons, would enable recommendations based on new lesion development while patients are treated with disease modifying drugs.

He also argued that a standardized MRI procedure in multiple sclerosis is crucial for detecting safety issues, such as the development of lesions indicative of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a serious viral infection in the brain.

But Rot believes that so far, there is no data that would indicate that patients treated with oral drugs or monoclonal antibodies have a poor prognosis with “MRI-only” worsening. Common clinical reasoning should be the guiding star when managing individuals with multiple sclerosis, and – given that more potent drugs are associated with more adverse effects – escalation therapy should be reserved for patients with a more realistic risk of poor prognosis.

Such a realistic assessment is, in Freedman’s view, highly dependent on MRI and its ability to detect when treatment is not effective when expensive and sometimes risky medications are used to harness MS. According to Freedman, MRI allows clinicians to do this assessment with more accuracy and in a shorter time than waiting for clinical symptoms to develop.

“Standardized MRI studies for evaluating MS have now been instituted in most centers. MRI burden and distribution is highly prognostic especially early,” Freedman said in the debate, adding, “There are many MRI evaluations that must be considered still investigational for monitoring response to treatment, but routine sequences can detect most new inflammatory activity threshold while on disease-modifying therapies.”

This is also important to define optimal treatment responses and, if necessary, to consider a switch in therapeutic approach, he said.

But Rot concluded that the main issues in considering MRI a proper tool to guide multiple sclerosis treatment are the lack of a proper reference imaging method, the interpretation reliability of MRI, and the fact that there is no evidence of disability prediction in patients treated with glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) and oral drugs. According to Rot, common clinical reasoning is the main factor in therapeutic decision-making.

Multiple Sclerosis News Today had the opportunity to conduct an exclusive interview with Prof. Montalban, the debate’s host, where he cautiously commented that concerning the use of MRI in the monitoring of disease progression, “We still don’t know exactly how to monitor one single individual using brain atrophy or other techniques … we need still a little bit of time to use this at the individual level.”

When asked about the challenging interpretation of complex MRI results, and the possible need for standardization in order for the technique to be considered a reliable and precise tool in disease and treatment monitoring, Montalban said, “From a technical point of view, this is very, very challenging and depends on the MRI you are using.”

He recalls an experiment where one patient underwent, on the same day, MRI scans in three different machines, yielding completely different results. “So we have to be very careful. Even using the same [software], different machines can make a difference, so there is still a long way,” he said.

Watch the complete interview with Prof. Montalban here: