Regular Exercise Found to Repair Damage to Neurons in Brains of Mice

Written by |

Voluntary running triggers a molecule called VGF, a nerve growth factor, that was seen to induce a brain repair mechanism in animals, researchers at The Ottawa Hospital and the University of Ottawa in Canada report. The findings have important implications for multiple sclerosis (MS) and other conditions caused by damage to the insulating tissue that protects nerve cells.

“We are excited by this discovery and now plan to uncover the molecular pathway that is responsible for the observed benefits of VGF,” David Picketts, senior author of the study and a senior scientist at The Ottawa Hospital, and professor at the University of Ottawa, said in a news release. “What is clear is that VGF is important to kick-start healing in damaged areas of the brain.”

The study, “Voluntary Running Triggers VGF-Mediated Oligodendrogenesis to Prolong the Lifespan of Snf2h-Null Ataxic Mice,” was published in the journal Cell Reports.

Clinical studies have shown that physical exercise protects against brain atrophy, enhances cognitive function, and slows neurodegenerative disease progression and disability. Studies in rodents have confirmed that exercise regimens improve motor and cognitive functions in a variety of neurodegenerative models, including MS. However, understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which exercise halts neurodegeneration or protects against it remains poor.

In their experiments, the researchers used mice modified to have a small cerebellum, the brain area that controls balance and movement. These mice, in general, had difficulty walking and lived only 25 to 40 days.

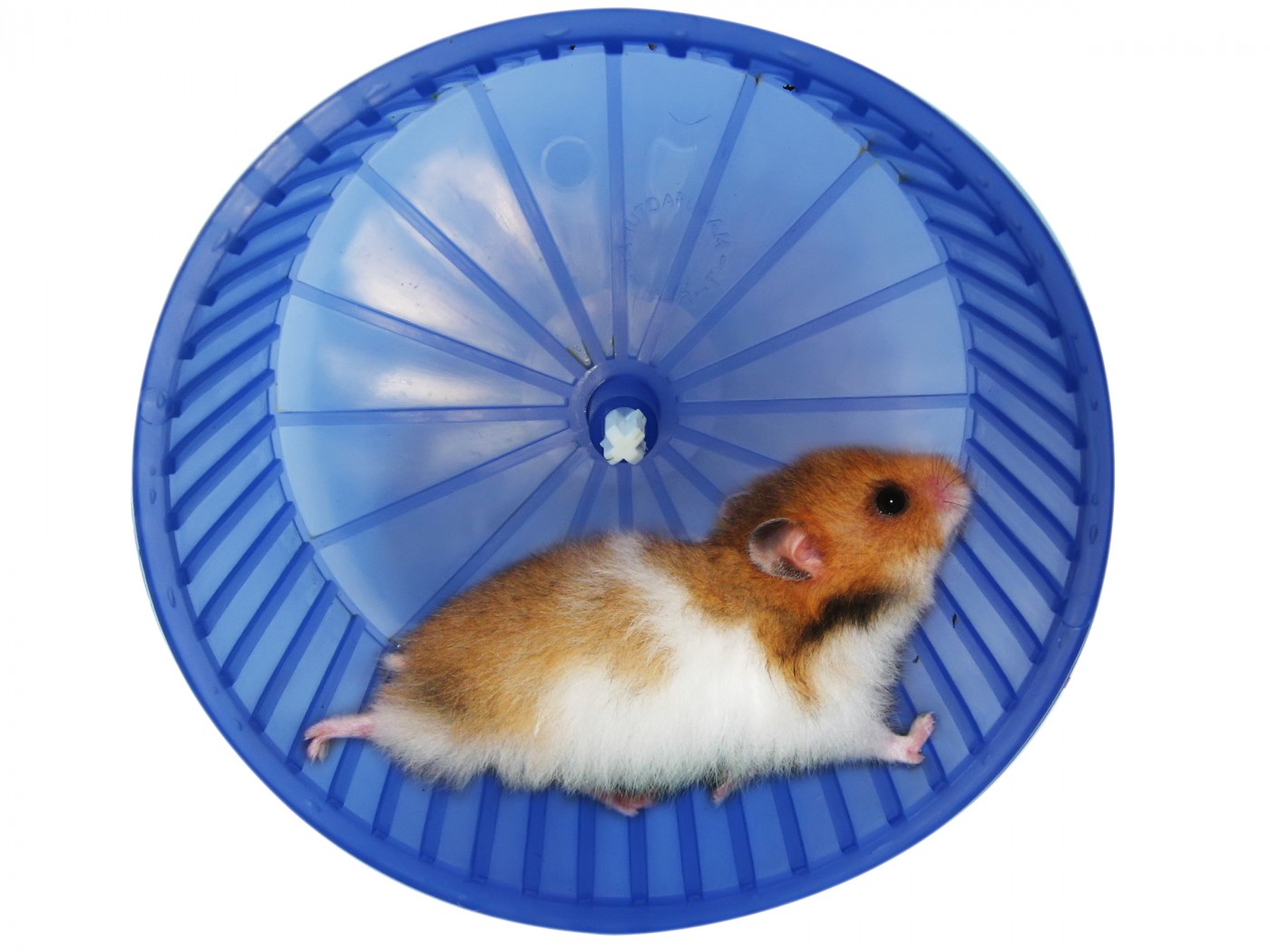

Mice that were allowed to run freely on a wheel, however, lived for more than 12 months, a more typical mouse lifespan. Compared to sedentary mice, researchers observed that these animals also had a better sense of balance and gained a healthier weight.

But to maintain these benefits, the mice had to keep running on a regular basis; once the running wheel was removed from their environment, balance problems and other symptoms reappeared and their lifespans shortened.

Researchers then examined the brains of animals in the two groups, and observed that the running mice had significantly more insulation in their cerebellum than the sedentary mice.

Next, the team looked at differences in gene expression between the mice groups.

Researchers found that the VGF nerve growth factor played a critical role in protecting the coating that surrounds and insulates nerve fibers, called myelin. The molecule is one of the hundreds that the brain and muscles release into the body during exercise.

To further assess VGF’s role, the team injected a modified VGF protein (via a non-replicating virus) into the bloodstream of sedentary mice and observed that — similar to the running mice — better insulation formed in the damaged area of their cerebellum, and these mice showed fewer disease symptoms.

“We saw that the existing neurons became better insulated and more stable,” said Matías Alvarez-Saavedra, PhD, the study’s lead author. “This means that the unhealthy neurons worked better and the previously damaged circuits in the brain became stronger and more functional.”

More research now is needed, the researchers said, to determine if the VGF molecule might also be helpful in treating people with neurodegenerative diseases such as MS.