Myelin May Hold Raw Material for Immunizing MS Patients Against Demyelination

Written by |

Immunization with molecules present specifically in myelin may be a new approach to treating multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a recent study that found that the mouse version of such molecules could stop ongoing disease processes in an MS mouse model.

The study, “Targeting Non-classical Myelin Epitopes to Treat Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis,” appeared in the journal Scientific Reports.

Current MS medications have rather broad actions on immune cells and, subsequently, a wide range of side effects. Researchers at Loma Linda University in California argued that optimally, an MS treatment should narrowly aim to prevent autoimmune destruction of myelin, without affecting immune processes that protect patients from infections and other hazards.

According to the research team, antigen-specific therapy is the way to go. Such a treatment would target hazardous autoimmune cells that react directly with myelin, and turn them into myelin-specific regulatory T-cells.

Were this possible, such regulatory T-cells (also called Tregs) would work to counteract an immune attack on myelin, without compromising other immune functions.

Earlier studies demonstrated that molecules called Qa-1 have unique properties that may lend themselves to such an approach. Qa-1 is an epitope, meaning it is the part of an antigen protein to which antibodies bind.

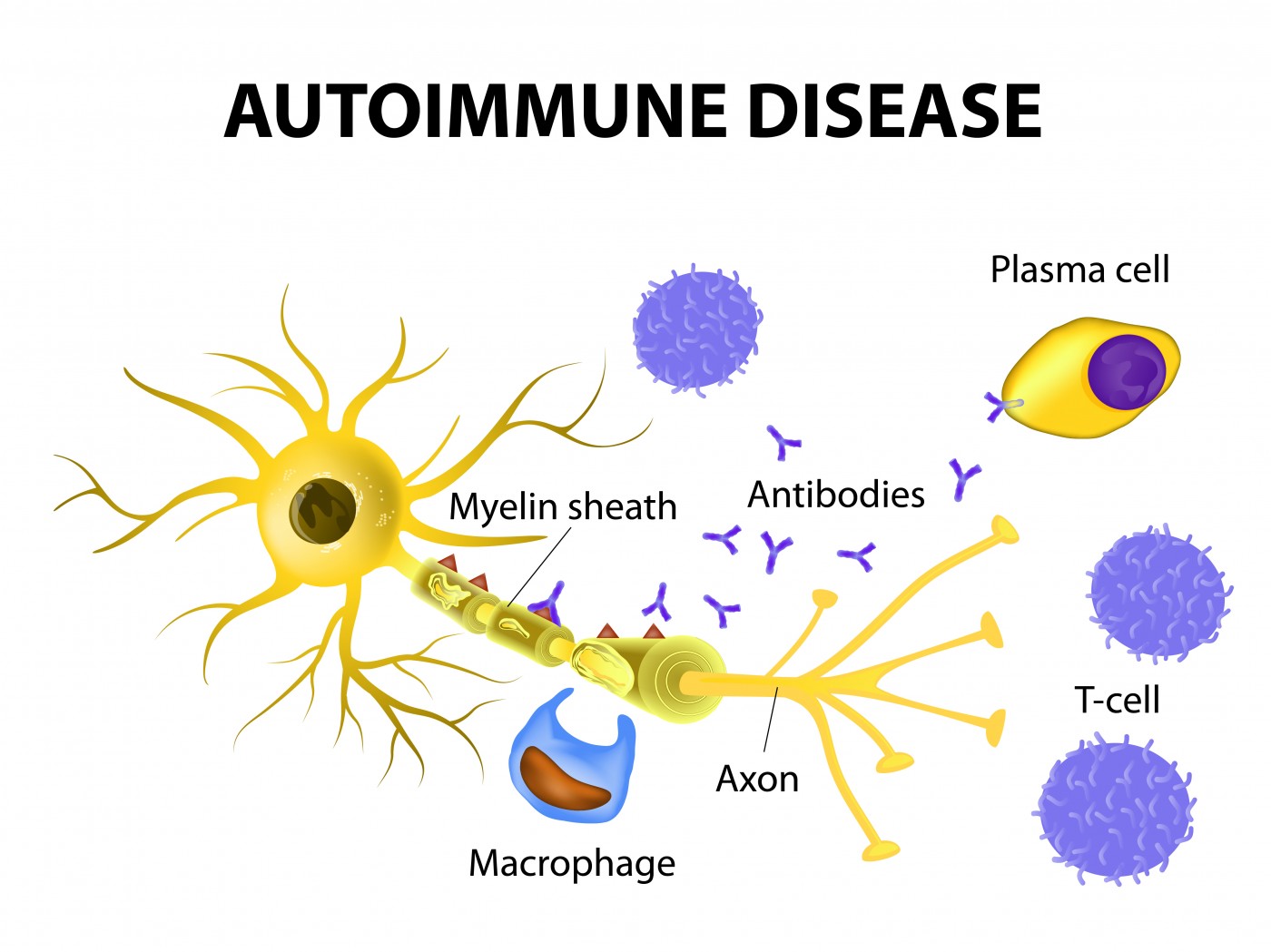

In experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE), a mouse model of MS, autoimmune cells carry such epitopes — acting much like a law enforcement “wanted” poster to alert the immune system to destroy myelin with these molecules on its surface.

But these molecules can also be used to activate Qa-1 specific Tregs, and mouse studies have shown that Qa-1 molecules, collected from the autoimmune cells that attack myelin, can be used as a vaccine, boosting Tregs to counteract disease processes.

To apply this approach in patients, however, scientists first need to know which autoimmune cells are attacking myelin, so as to isolate the right epitopes. But in humans, it is difficult to determine the precise, responsible cells. So, instead, the research team decided to try another approach — to isolate such epitopes directly from a protein present in myelin.

Again focusing on mice, the team started searching for Qa–1-type epitopes in a myelin protein called MOG. They discovered that such an epitope existed, and did activate Tregs that specifically worked to counteract attack on cells carrying Qa-1.

After isolating the Qa-1 molecule from myelin, the team then used it to immunize mice with EAE. This increased the number of regulatory cells in the brains of the mice, and the mice had a slower disease progression. But to explore whether the Tregs were truly responsible for this good outcome, the team took the experiment one step further.

The researchers isolated Tregs from a mouse that had received immunization, and transferred those cells to mice with EAE that had not been vaccinated. The mice receiving the immune-cell transplant also showed evidence of disease suppression.

This study details a new regulatory mechanism mediated by Treg cells, and its authors propose that immunizing patients with myelin-specific epitopes (human homologues of Qa-1 epitopes) is a promising therapy for MS.