Neurological Disease’s Progression Slows with Lowering of Iron Load in Brain, Study Finds

Written by |

Deferiprone, a compound that lowers iron levels in the bloodstream by binding to iron molecules, can slow progression of a severe neurodegenerative disorder called pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), a study reports.

Because a toxic buildup of iron in the brain is also associated with multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases, these findings — based on a Phase 3 clinical trial — may be relevant to these disorders as well.

The study, “Safety and efficacy of deferiprone for pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial and an open-label extension study,” was published in the journal The Lancet Neurology.

PKAN is a rare, genetic disorder characterized by dystonia (involuntary muscle movements), and linked to the accumulation of iron in certain regions of the brain.

Deferiprone is an iron chelator (binding agent) normally used to treat the iron overload that can follow blood transfusions in people with thalassemia, a heredity disorder marked by an inability to produce hemoglobin — essential for oxygen transport in the bloodstream — at all or in adequate levels.

The compound is small enough to cross the blood-brain barrier (the selective, semipermeable membrane that protects the brain from possible insults carried in the blood). As such, deferiprone should be able to reach excessive iron deposits in the brain.

Researchers in the U.S. and Germany carried out a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT01741532) to assess whether deferiprone might lower iron accumulation in the brain and slow disease progression in PKAN patients.

Their study enrolled 88 children and adults, ages 4 and older, who were randomly assigned to either oral deferiprone (a total of 30 mg/kg each day, split into two daily doses) or a placebo for 18 months.

Its primary goals were changes in the severity of dystronia from the study’s start through to its finish, using the Barry-Albright Dystonia (BAD) scale that measures dystonia severity in eight regions of the body, and self-reported improvements in symptoms as determined by scores on the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) scale at month 18.

Those 76 who completed the trial were eligible to continue — or begin — deferiprone treatment for 18 months in an open-label extension study (NCT02174848).

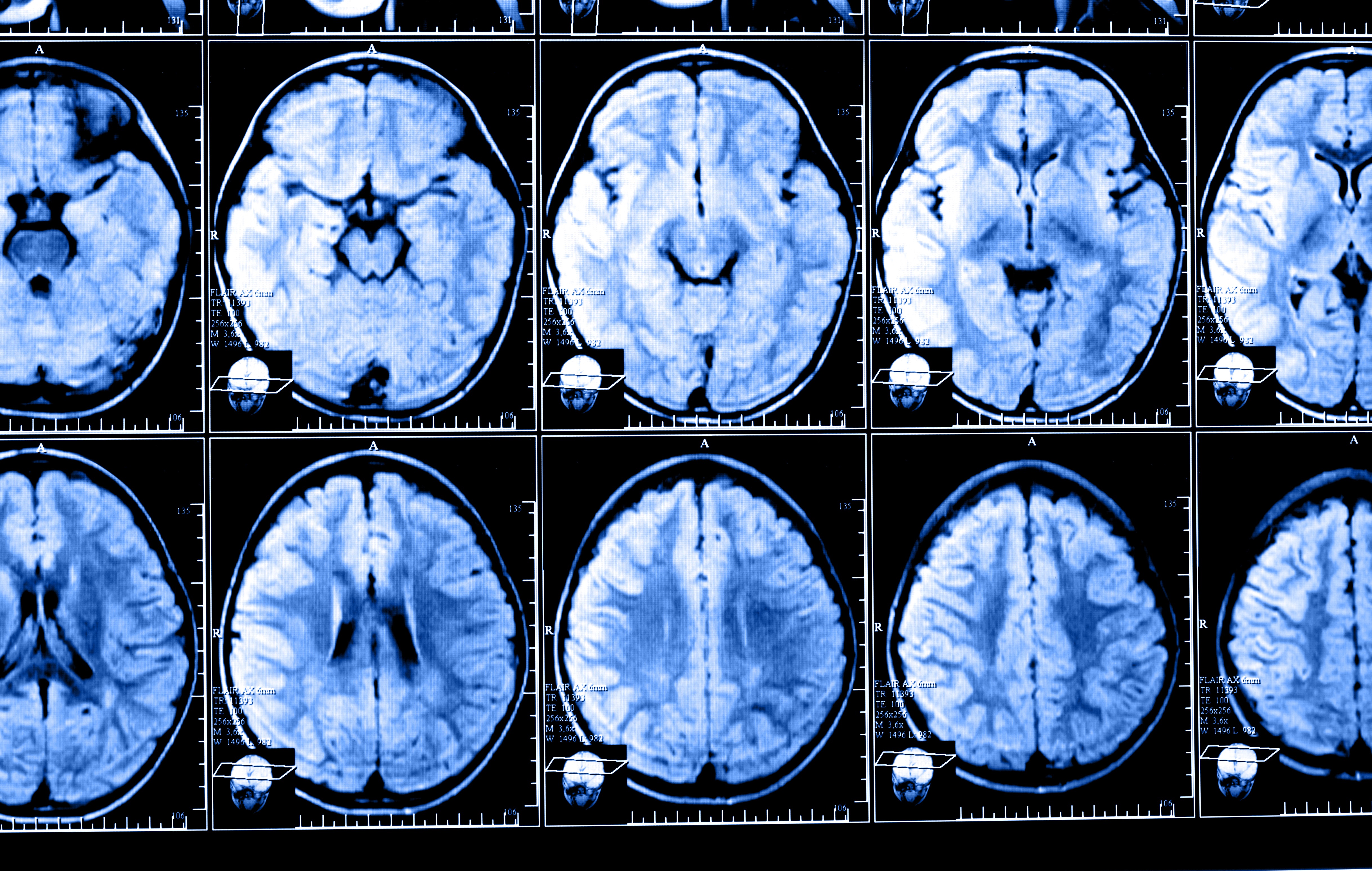

Results of the main study, which concluded treatment in April 2015, found deferiprone did lower the amount of iron in patients’ brain as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. The percentage of treated patients using additional medications to control their dystonia was also lower (11%) than those in placebo group (21%).

But BAD scores did not show significant changes in dystonia between the two groups — scores on this scale worsened by a mean of 2.48 points in deferiprone-treated patients and by a mean of 3.99 points in the placebo group. Likewise, “no subjective change was detected” in terms of patient-reported improvements, the scientists reported.

The scientists did find, however, that those who switched from placebo to deferiprone in the open-label extension had a slowing of more than 60% in disease progression. Their mean BAD scores dropped from 4.4 points (at 18-month close of main study) to to a mean of 1.4 points (at the 18-month close of the extension study), compared to a mean change of 1.9 points to 1.4 points in treated patients at both timepoints.

This study “provides the first indication of a decrease in disease progression in patients with neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation,” the researchers wrote.

“Deferiprone was well tolerated, achieved target engagement (lowering of iron in the basal ganglia), and seemed to somewhat slow disease progression at 18 months, although not significantly, as assessed by the BAD scale. These findings were corroborated by the results of an additional 18 months of treatment in the extension study,” the study reported.

“Any slowing of disease progression in this devastating disorder is an important step,” Thomas Klopstock, professor in the department of neurology at the Friedrich-Baur-Institute, University of Munich, and the study’s lead author, said in a news release from the University of California, San Francisco, written by Lorna Fernandes.

Deferiprone appeared to be safe, with placebo and treatment groups reporting similar side effects. Anemia was the exception, as 21% of deferiprone treated patients reporting this side effect compared to no patients in the placebo group.

The study was part of the TIRCON (“Treat Iron-Related Childhood-Onset Neurodegeneration”) project, a large collaborative project involving several research institutions worldwide, and focused on improving the diagnosis and treatment of people with rare neurological disorders associated with iron accumulation in the brain.