‘Transcient’ Damage to CNS Seen with Chemotherapy Used in Stem Cell Transplants for MS

Written by |

A high-dose chemotherapy combination given to wipe out the immune system before its rescue with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (aHSCT) can cause “transient” damage to neurons and supporting cells of the central nervous system in people with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), a Canadian study reports.

Nonetheless, its researchers believe that the risk of such neuronal toxicity is offset by the benefits of the aHSCT procedure in aggressive MS cases.

The study, “Neurotoxicity after hematopoietic stem cell transplant in multiple sclerosis,” was published in the journal Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology.

aHSCT is an intensive yet effective treatment, particularly used to rebuild the immune system of people with aggressive MS.

The procedure begins with collecting a patient’s own (meaning autologous) healthy hematopoietic stem cells from the bone marrow, followed by immunoablation — the wiping out of the immune system — with a high-dose chemotherapy combination that kills the patient’s immune cells. The hematopoietic stem cells are then infused back to the person to generate a new and healthy immune system.

Intensity and duration of the chemotherapy given varies among centers.

In Canada, the chemotherapy regimen used in clinical practice is particularly intense and involves high doses of two agents, cyclophosphamide and busulfan. This combination is known to penetrate the central nervous system (CNS, brain and spinal cord), and to kill the CNS immune cells (called microglia) that go awry in MS.

Previously, researchers in Canada noted faster brain volume loss in MS patients over the six months following aHSCT. This was interpreted as a false (pseudo) shrinkage of brain volume due to lesser inflammation. They also thought that the toxicity related to the chemotherapy regimen itself could be a contributing factor, as chemotherapy can affect cognitive and memory abilities — what patients refer to as ‘chemo brain’ and ‘chemo fog.’

To test these interpretations, a team led by researchers at the University of Ottawa measured the levels of two markers — serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) and serum glial fibrillary acidic protein (sGFAP) — in the blood (serum) of MS patients before and after the chemotherapy regimen in aHSCT.

sNfL has been proposed as a marker of neuron degeneration and damage, and sGFAP is a marker of astrocytes, cells involved in the provision of nutrients to neurons, the repair of nervous tissue following injury, and in facilitating neurotransmission (essential in nerve cell communication).

Researchers measured the levels of these two markers in blood samples from 22 MS patients with aggressive disease, all enrolled in the Phase 2 BMT trial (NCT01099930) in Canada. Blood samples were collected at specific times (three, six, nine, and 12 months) before and after aHSCT. Aggressive disease for this study was defined as having “a poor predicted 10-year prognosis [likely course].”

Blood samples from another 28 people of similar ages and with non-inflammatory diseases (including migraine, fibromyalgia, anxiety, Bell’s palsy, labyrinthitis, and depression) were used as controls.

sNfL levels prior to aHSCT were seen to be significantly elevated in the blood of MS patients (mean of 21.8 pg/mL) compared with controls (6.4 pg/mL). So too were blood levels of sGFAP: 107.4 pg/mL in MS patients versus 50.7 pg/mL in controls.

Three months after aHSCT, levels of sNfL significantly increased by 32.1% (from 21.8 to 28.8 pg/mL), and sGFAP levels by 74.8% (from 107.4 to 187.7 pg/mL) in 15 patients with available three-month data, compared to their pre-treatment levels. In two of these 15 people, both sNfL and sGFAP levels were lower three months after treatment.

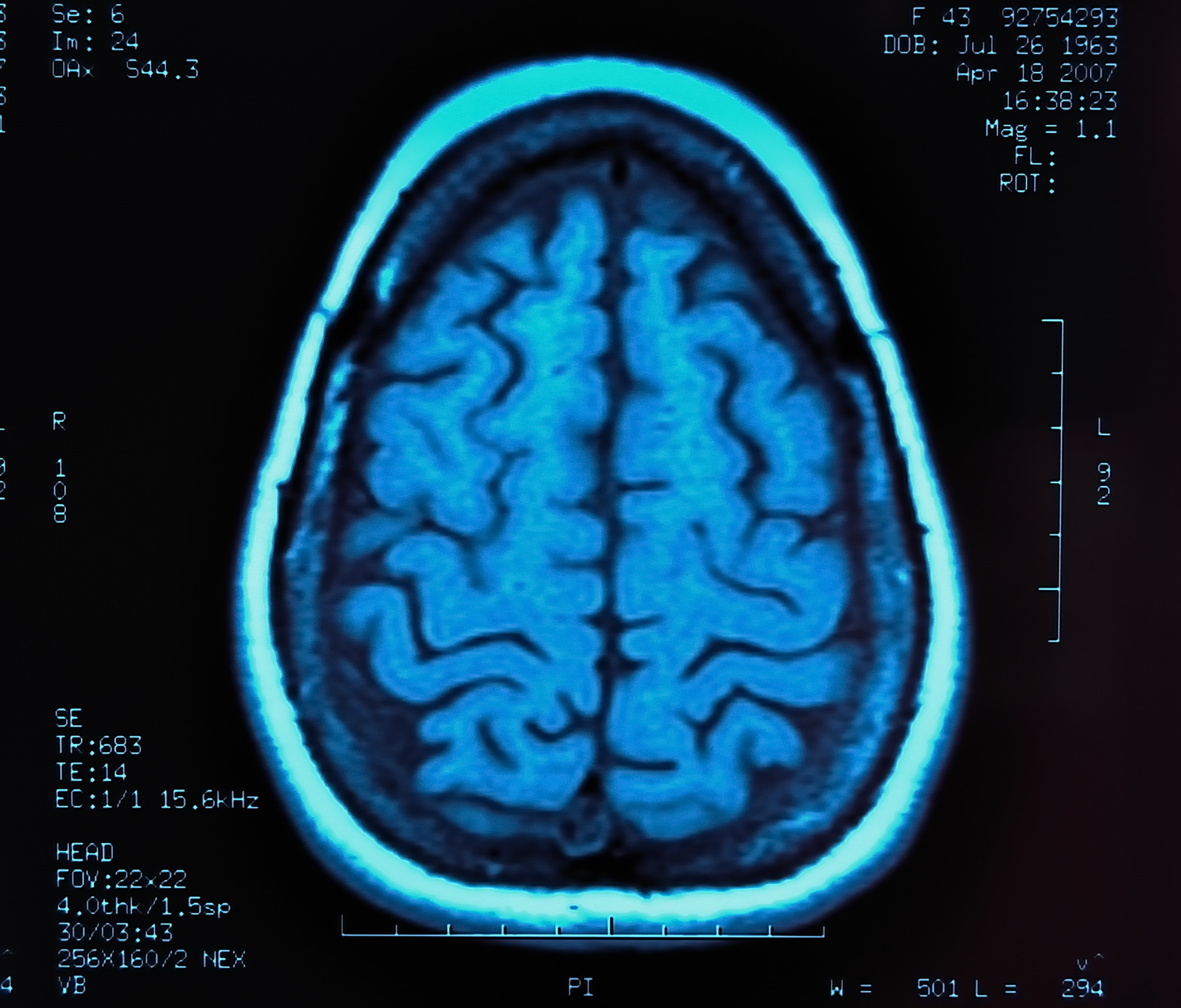

Further analysis looked at changes from baseline (study start) and three-month post-aHSCT measures of sNfL levels and grey matter volume loss. This was done to look “for correlations between early serum biomarker changes with clinical and MRI markers of possible neurotoxicity,” the researchers wrote.

Their analysis found correlations at all early time points — months one, two, four and six — but not at nine or 12 months post-treatment, highlighting that associated increases in both sNfL and MRI grey matter volume loss “are temporary phenomena in the first year following IHASCT,” they wrote.

Patients given the highest dose of busulfan (more than 700 mg) had the highest levels of sNfL and a greater extend of grey matter loss, shown by MRI, at three months post-treatment.

The chemotherapy regimen used increases sNfL and sGFAP levels in the first few months after treatment, the study noted, with sNfL increases correlated with the total busulfan dose given. The result is a “transient worsening of post‐treatment EDSS score as well as MRI volume loss, especially in the grey matter,” the researchers wrote.

“This study is the first to correlate these increases [rises in brain atrophy and serum markers of neurotoxicity] with doses of chemotherapy administered” in aHSCT, they added.

“Although we see transient neurotoxicity likely related to busulfan in this study, this has to put in the context of their highly active refractory disease,” the team concluded. “While the long-term effects of chemotherapeutic neurotoxicity are not known, in cases of aggressive MS, short-term chemotherapy-related neuronal toxicity may be a risk that is greatly offset by the benefit of long-term freedom from disease-related inflammation.”