Gut Mucus May Help Ease MS, Other Neurological Diseases, Review Suggests

Written by |

Tweaking the protective properties of the gut mucus, a layer lining the inside of the gut, to boost the proliferation of good bacteria potentially could halt the development of neurological disorders, like multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a review of more than 100 studies.

The review, “The Role of the Gastrointestinal Mucus System in Intestinal Homeostasis: Implications for Neurological Disorders,” was published in the journal Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology.

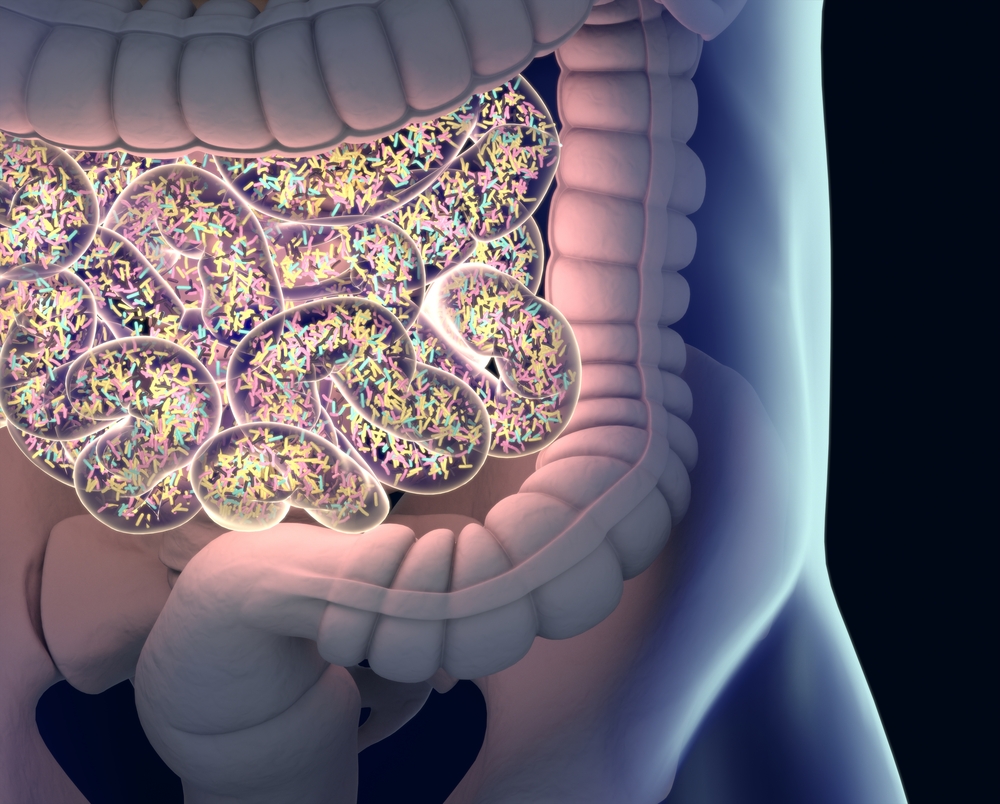

Our gut is lined with a mucus layer that is key for a healthy gastrointestinal system, with properties adapted to each segment of the gut. In the small intestine its composition is more porous to facilitate nutrient absorption, while in the colon it becomes thicker, acting as a physical barrier against harmful bacteria but allowing the natural, beneficial community of microbes living in the gut — the gut microbiome — to thrive.

Moreover, the gut is innervated not only by the autonomic nervous system, but also by its own network of neuronal cells that regulate the functions of the gastrointestinal tract, called enteric nervous system (ENS).

Increasing evidence shows that changes in the gut and its microbiome have far-reaching implications, and are commonly found in people with neurological disorders, such as autism, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, and also MS.

Now, researchers at the RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, reviewed 113 neurological, gut and microbiology studies suggesting that changes in the gut mucus composition could play a role in neurological disorders.

“Mucus is a critical protective layer that helps balance good and bad bacteria in your gut but you need just the right amount — not too little and not too much,” Elisa Hill-Yardin, said in a press release. Hill-Yardin is a professor at School of Health and Biomedical Sciences, RMIT University and the study’s senior author.

“Researchers have previously shown that changes to intestinal mucus affect the balance of bacteria in the gut but until now, no one has made the connection between gut mucus and the brain,” Hill-Yardin said.

In MS patients, several studies have reported an imbalance of the gut microbiome with abundance of pro-inflammatory microbes, such as the bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, and a reduction of protective microorganisms, like Parabacteroides distasonis.

This imbalance toward the growth of pro-inflammatory bacteria may “alter the composition of the mucus layer and therefore may exacerbate core symptoms of these disorders,” researchers wrote.

The team now reveals different types of bacteria present in the gut of patients with neurological disorders.

“Our review reveals that people with autism, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s and Multiple Sclerosis have different types of bacteria in their gut mucus compared with healthy people, and different amounts of good and bad bacteria,” said Hill-Yardin. “It’s a new gut-brain connection that opens up fresh avenues for scientists to explore, as we search for ways to better treat disorders of the brain by targeting our ‘second brain’ — the gut.”

These findings add to existing evidence supporting the potential of gut-microbiome targeted therapies for easing MS and other neurological disorders.

“If we can understand the role that gut mucus plays in brain disease, we can try to develop treatments that harness this precise part of the gut-brain axis,” said Hill-Yardin.

“Overall, this review highlights that mucus properties could be impaired in neurological disease and provides new avenues for clinically relevant research into GI [gastrointestinal] dysfunction in these disorders,” the researchers wrote.

Hill-Yardin believes that “microbial engineering, and tweaking the gut mucus to boost good bacteria, have potential as therapeutic options for neurological disorders.”