Cancer Researchers’ Discovery May Benefit MS Studies

Written by |

In an unexpected discovery, scientists working to understand the biological underpinnings of brain tumors found that increasing the activity of a protein receptor called PDGFRA reduces the production of myelin — the fatty coating that is lost in multiple sclerosis (MS) — in the nervous system.

“We saw that too much PDGFRA interfered with differentiation of progenitor cells that give rise to cells that make myelin,” one of the researchers, Oren Becher, MD, from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Illinois, said in a press release.

“Blocking this receptor might prove to be a novel strategy to treat myelination disorders like multiple sclerosis,” Becher said.

Becher and colleagues published their findings in Brain and Behavior, in the study, “Prenatal overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor A results in central nervous system hypomyelination.”

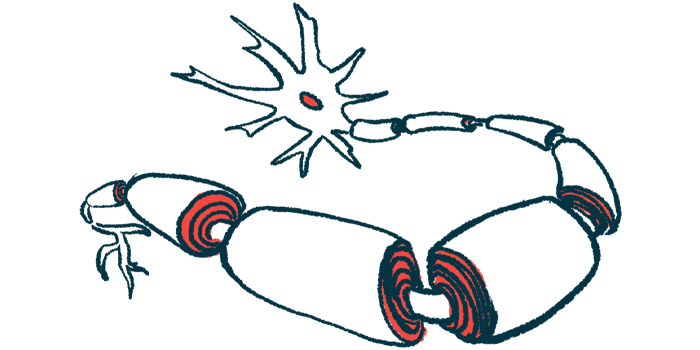

The researchers were studying oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), a specific type of stem cells able to grow and mature into cells called oligodendrocytes, which are the chief makers of myelin in the nervous system. Myelin is a fatty substance that wraps around nerve fibers to help them send electrical signals. In MS, inflammation that damages the myelin sheath is what leads to disease symptoms.

To survive and grow, OPCs depend on the activity of the receptor protein PDGFRA, which lets the cells sense a signaling molecule called PDGF-A (platelet-derived growth factor-A). In brain cancers caused by the out-of-control growth of OPCs, this protein often is mutated or over-expressed (overactive).

Seeking to better understand the role of PDGFRA in these kinds of tumors, the researchers used genetic engineering techniques to make mice that express high levels of the human PDGFRA protein in their OPCs.

Unexpectedly, these mice did not develop brain tumors. Instead, analyses of their brains showed abnormally low levels of myelin, termed hypomyelination. Further analyses suggested that mice with increased PDGFRA levels had fewer OPCs in their brains by the time they were of weaning age.

As a result, the mice experienced impaired balance and tremors, which the researchers said was “reminiscent of symptoms commonly seen in mouse models of hypomyelination.”

They added that these mice “may represent a novel model for investigating hypomyelinating disorders and treatments.”

Notably, prior studies had shown that mice engineered to lack PDGF-A — the signaling molecule that activates PDGFRA — also exhibit hypomyelination, which “suggests a developmental balancing act where too little or too much of PDGF-A/PDGFRA signaling is deleterious to OL [oligodendrocyte] development,” the researchers wrote.

More specifically, the researchers noted that PDGF-A/PDGFRA signaling is necessary to maintain the health and survival of OPCs. However, this signaling also may work to keep the OPCs in an immature state, preventing them from developing into myelin-producing oligodendrocytes.

“The exact mechanism by which PDGFRA overexpression impacts OL development … will be evaluated in future studies,” the investigators wrote.