How Stem Cell Transplant Can ‘Reset’ Immune System in MS: Study

Researchers examine dynamics of T-cell recovery after aHSCT in 27 MS patients

Written by |

Following an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (aHSCT) in people with multiple sclerosis (MS), the population of “naïve” T-cells — components of the immune system that enable the body to fight off new, unrecognized infections — is completely renewed but some memory T-cells, which are responsible for rapid responses against known pathogens, are retained, a study in Zurich has found.

Researchers sought to understand what happens to the immune system after stem cell transplants in people with MS, with a particular focus on how T-cells, a type of immune cell that drives inflammation in MS, regenerated and how populations of these cells changed.

The dynamics of T-cell recovery after a transplant may “provide a valuable resource for understanding the mechanisms mediating the efficacy of aHSCT in patients with MS,” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Dynamics of T cell repertoire renewal following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis,” was published in Science Translational Medicine.

Stem cell therapy aims to ‘reset’ a person’s immune system

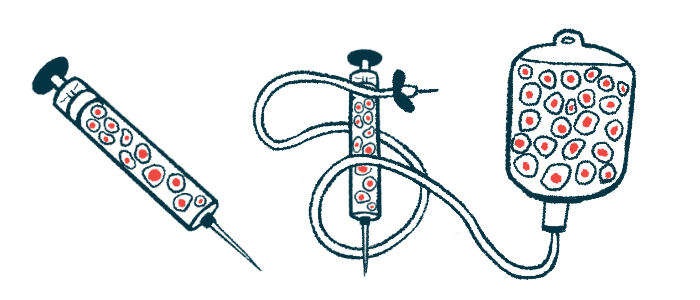

aHSCT, sometimes called stem cell therapy, is a procedure that aims to “reset” a person’s immune system. Simplistically, it involves collecting blood stem cells from a patient’s bone marrow or blood, then using high doses of chemotherapy or radiation to wipe out the patient’s immune system. The collected stem cells are then infused back into the patient to repopulate the immune system. This can be an effective treatment for MS, especially in young patients with highly active forms of the disease.

About “80 percent of patients remain disease-free long-term or even forever following an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant,” Roland Martin, MD, co-author of the study, a recently retired professor from the University of Zurich, said in a university press release.

Martin’s clinic at the University Hospital Zurich is the only institution in Switzerland that is approved to administer this treatment — prior to that approval, people with MS in Switzerland would generally have to travel to Russia, Israel, or Mexico for the treatment.

aHSCT is still not approved to treat MS in many countries, including the U.S., due to the lack of large Phase 3 clinical trials assessing the safety and efficacy of this approach against high-efficacy disease modifying therapies.

“Phase 3 studies cost several hundred million euros, and pharmaceutical companies are only willing to conduct them if they will make money afterward,” Martin said, noting that medications used in the aHSCT procedure are no longer patent-protected.

“I am therefore very pleased that we have succeeded in obtaining approval for the treatment from the Federal Office of Public Health and that health insurers are covering the costs,” added Martin.

80 percent of patients remain disease-free long-term or even forever following an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant

Researchers analyzed T-cell populations in 27 MS patients post-transplant

Although the general theory behind aHSCT is well-established, exactly how the immune system changes after the procedure is not completely understood.

“Previous studies have shown the basic workings of the method, but many important details and questions remained open,” Martin said.

Thus, Martin and other researchers conducted detailed analyses on how immune cell populations changed following aHSCT in 27 people diagnosed with MS. Specifically, the team focused on T-cells.

These cells are equipped with a specialized receptor, aptly called a T-cell receptor or TCR. Each T-cell receptor is able to recognize a single specific antigen, or target — for example, a piece of a virus or bacteria. In MS, inflammation is driven in part by T-cells whose TCR accidentally targets parts of the brain and spinal cord.

When T-cells are first generated in the body, they are said to be “naïve.” When a naïve T-cell’s TCR binds to its antigen, the cell activates, spewing out inflammatory signaling molecules to sound the alarm and rapidly dividing to make more T-cells with the same TCR.

Most of these newly made T-cells will go to fight the infection, but some of them will stick around in the body’s tissue as “memory” T-cells. These memory cells can then help the body fight off the threat if it’s ever encountered again — this type of immunological memory is the basic principle by which vaccines work.

The researchers found that, immediately following aHSCT, “naïve T cells are barely detectable,” whereas memory T-cells “quickly reconstitute to pre-aHSCT values.”

Closer analyses of the memory cells showed that they expressed high markers of senescence and exhaustion — in other words, they appeared to be largely inactive and unable to divide — and they showed reduced reactivity against MS-relevant antigens.

Comparisons of the TCR repertoire in memory cells before and immediately after aHSCT revealed a 26% overlap, which decreased to 15% at one year following aHSCT.

These data suggest that although memory cells are detectable following aHSCT, “they are pre-damaged due to the chemotherapy and therefore no longer able to trigger an autoimmune reaction,” Martin said.

By contrast, following aHSCT “the naïve TCR repertoire entirely renews,” the researchers wrote. This process involved a marked boost in activity in the thymus, an organ that’s critical for T-cell development.

“Adults have very little functioning tissue left in the thymus,” Martin said. “But after a transplant, the organ appears to resume its function and ensures the creation of a completely new repertoire of T cells which evidently do not trigger MS or cause it to return.”