Common Allergy Treatment Restores Protective Neuron Coating in MS, Trial Suggests

Written by |

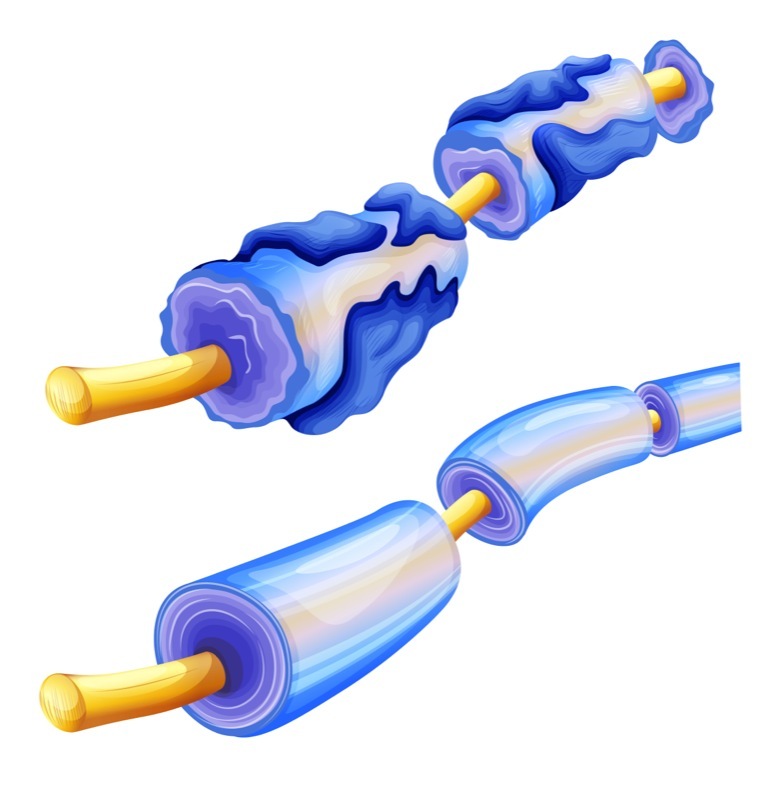

Scientists have been trying to find a way to restore a protective covering around nerve cells whose loss leads to the neuron damage associated with multiple sclerosis.

A team at the University of California, San Francisco may have found a way to do it. And perhaps surprisingly, the possible solution is an over-the-counter allergy drug.

A Phase 2 clinical trial showed that the antihistamine clemastine fumarate helped people with a chronically damaged optic nerve. The therapy led to faster firing of patients’ vision neurons, according to a report in the journal The Lancet. It also slightly improved how well the patients could distinguish contrast.

While the effect was modest, researchers said the study proved that rejuvenation of the protective of the protective neuron coating — the protein myelin — can occur in those with even chronic nerve-cell damage. The findings are a starting point for the development of more effective treatments, they said.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time a therapy has been able to reverse deficits caused by MS,” Dr. Ari Green, principal investigator of the trial, said in a press release. “It’s not a cure, but it’s a first step towards restoring brain function to the millions who are affected by this chronic, debilitating disease.”

The research team focused on vision damage In the Phase 2 ReBUILD trial (NCT02040298) for a simple reason: Vision is commonly affected in MS, and there are reliable ways to measure the speed of neurons in the brain that are linked to vision.

Their study was titled “Clemastine fumarate as a remyelinating therapy for multiple sclerosis (ReBUILD): a randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial.”

How an allergy therapy ended up in the MS field

The team’s choice of compound was not random. Earlier screening of compounds approved for other diseases showed that clemastine fumarate activates oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. These are cells involved in producing and wrapping myelin around nerve cell axons, or long, slender projections of neurons.

Researchers confirmed this finding in lab-grown cells and animals with myelin damage before deciding to test it in patients with chronic neuron damage.

“People thought we were absolutely crazy to launch this trial, because they thought that only in newly diagnosed cases could a drug like this be effective,” said Dr. Jonah R. Chan, a Debbie and Andy Rachleff Distinguished Professor of Neurology at UC-San Francisco.

“Intuitively, if myelin damage is new, the chance of repair is strong,” said Chan, the study’s senior author. “In the patients in our trial the disease had gone on for years.” But “we still saw strong evidence of repair” with clemastine fumarate, he said.

Measuring neuron speed

The team recruited 50 patients with chronic damage to their optic nerve for their study. They used a cross-over design to improve its statistical power.

Participants were split into two groups. One received clemastine fumarate for 90 days and then a placebo for 60 days. The other received a placebo first and then the drug. Then the groups switched, and the procedure was repeated. Neither patients nor the physicians in the study knew which group patients belonged to.

To assess potential effects of the drug, researchers measured what is known as visual-evoked potentials, or how fast neurons that govern sight fire in response to changes in light.

They used scalp electrodes to measure signals in the part of the brain that oversees vision. This area is located in the back of the brain. In people with optic nerve damage, it takes longer for a nerve signal — a response to a flickering pattern on a screen — to travel between the eye and the back of the brain.

Researchers discovered that the speed of the signals was significantly improved in the group that started with clemastine fumarate. The effect persisted after the group was put on a placebo for two months, suggesting that the improved neuronal function was long-lasting.

The team also measured participants’ ability to detect changes in visual contrast. It improved after the treatment, but not enough to reach statistical significance.

Restoration of myelin is called remyelination. The team failed to prove it had occurred because “we still don’t have imaging methods that have been proven to be able to detect remyelination in humans,” Chan said.

But the team said myelin regeneration was the only plausible explanation for the results. That’s because it’s well-known that myelin speeds up nerve signals.

The first step

Although the results were noteworthy, the improvements were “modest and probably not of a clinically meaningful magnitude,” in the opinion of two researchers from the Cleveland Clinic and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. They also pointed out that it might be difficult to increase the dose of clemastine fumarate or the duration of treatment because of side effects.

The UC-San Francisco research team is not trying to claim that their study is the final solution to remyelination.

“This is the first step in a long process,” said Green, who is also a Debbie and Andy Rachleff Distinguished Professor of Neurology, chief of the university’s Division of Neuroinflammation and Glial Biology, and medical director of the UCSF Multiple Sclerosis and Neuroinflammation Center.

“By no means do we want to suggest that this is a cure-all,” he said. “We want to ground-truth myelination metrics. We’re designing the crucible that’s going to be used to test any future method for detecting remyelination.”

The researchers who wrote the commentary shared this opinion.

“Although clemastine fumarate probably is not the final answer to the search for repair-promoting drugs to treat multiple sclerosis, the ReBUILD trial represents a watershed milestone in that quest,” they wrote.