Central Vein Sign Maintains Potential as MS Diagnostic Marker, European Study Shows

Written by |

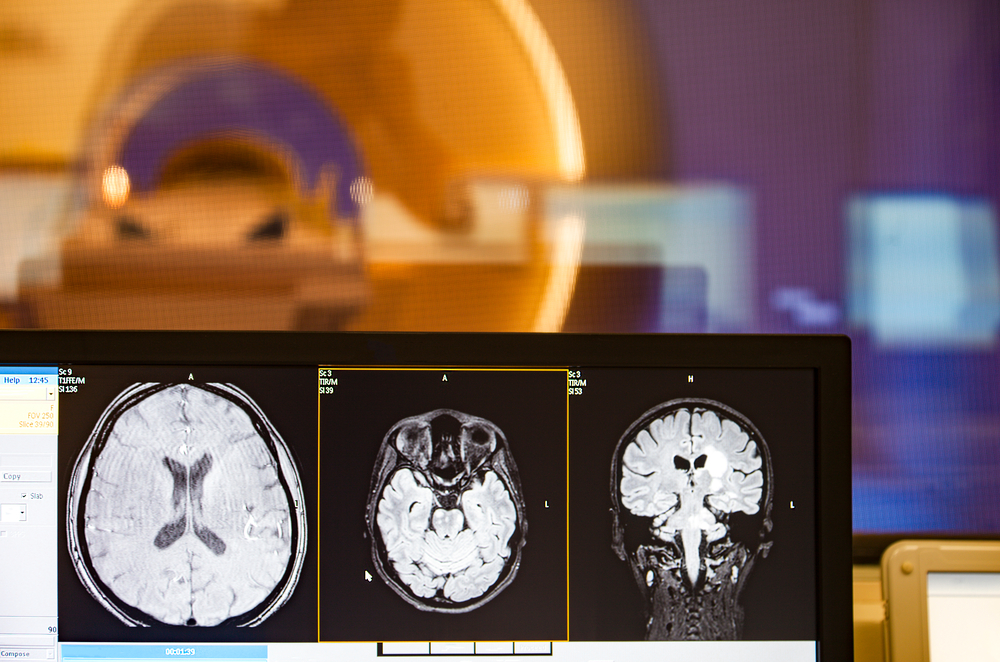

Detecting changes to the brain’s central vein using common magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans is a useful and accurate strategy to enhance diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS), a new study shows.

Analysis of more than 4,000 brain lesions, obtained from contrast-enhanced MRI scans collected from eight neuroimaging European centers, showed that detection of the so-called central vein sign (CVS) was able to differentiate patients with MS, including those with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), from non-MS patients with similar brain lesions.

Researchers also explored the best criteria and imaging protocols to apply in the clinic. More studies are now warranted to confirm CVS application in clinical practice.

The study, “Evaluation of the Central Vein Sign as a Diagnostic Imaging Biomarker in Multiple Sclerosis,” was published in the journal JAMA Neurology.

CVS has been proposed as a highly sensitive and specific biomarker to help differentiate MS from other conditions that have brain imaging features similar to those seen in MS patients.

The region surrounding brain’s central vessels is thought to be a site where inflammation is more likely to outbreak, leading to lesions around these veins (known as perivenous lesions) that can be detected by MRI scan.

CVS refers to the visualization of such veins inside brain lesions, which is thought to reflect loss of nerve cells’ myelin protective sheath due to inflammation (demyelination), and may aid the diagnosis of MS. The diagnostic value of CVS, however, remains to be proven in a broader setting, across multiple centers and a variety of imaging protocols.

Most findings supporting this application come from ultra high-field MRI studies, using high resolution scanners that operate at field strengths of 7 Tesla, or 7T, and above. These scanners are not available at most clinics, which normally operate with 1.5T or 3T instruments.

But some small, single center studies have provided evidence that conventional scanners like 3T can be used to detect CVS, opening the door to its wide clinical application.

Researchers conducted a study across multiple sites in Europe, to evaluate if CVS detected by standard 3T MRI scans could be used to discriminate MS from other non-MS conditions that echo MS brain lesions. Importantly, the team wanted to find the best imaging protocol and CVS criteria that could provide the most accurate method to identify patients with MS.

A total of 606 patients were included in the study. Participants were between 18 and 83 years old, except for a 14.7-year-old boy with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) and a 17.8-year-old girl with MS. Enrolled participants were taking part in ongoing studies and neuroimaging research databases across Europe. Patients underwent brain MRI scans from January 2010 to November 2016.

The MS group included 117 patients (19.3%) with CIS and 236 (38.9%) with relapse-remitting MS (RRMS). The non-MS group used for comparison included 32 people (5.3%) with aquaporin-4 antibody–positive NMOSD, 25 (4.1%) with systemic lupus erythematosus, 29 (4.8%) with migraine, 5 (0.8%) with cluster headaches, 20 (3.3%) with diabetes, and 142 (23.4%) with cerebral small vessel disease.

A total of 4,447 MRI-detected lesions were analyzed: 690 lesions in 98 participants with CIS, 2,815 lesions in 225 participants with RRMS. The remaining lesions were analyzed in the control group.

Scans included two imaging protocols: the commonly used 3T T2*-weighted that allows detection of myelin loss; and the susceptibility-weighted sequence, which is a more sensitive method to detect less marked chemical and structural changes.

Different CVS-based analysis criteria also were investigated, including the proportion and the absolute numbers of CVS-positive lesions and the lesion localization.

All these parameters were tested to see which ones yielded the best sensitivity (proportion of MS lesions correctly identified) and specificity (proportion of non-MS lesions correctly identified).

Results revealed that a CVS positive sign was found in 1,335 (47.4%) of 2,815 RRMS lesions and in 374 (54.2%) of 690 CIS lesions. In contrast, CVS was detected in 148 of 942 non-MS lesions (15.7%), a finding consistent among all studied non-MS subgroups.

These results translated into a sensitivity of 68.1% and a specificity of 82.9% for distinguishing MS from not MS if using a proportion threshold of 35% (the proportion of CVS-positive lesions). The presence of three or more CVS lesions had a sensitivity of 61.9% and specificity of 89% in differentiating MS and CIS.

Combined, the three lesions and the 35% threshold, yielded a “sufficient differentiation” with a sensitivity of 83.0% and a specificity of 68.3%.

T2*-weighted imaging demonstrated to be the most suitable protocol for identifying MS, with a sensitivity of 100%, compared to the susceptibility-weighted protocol that only had a sensitivity of 66.6% for discriminating MS from CIS.

These findings reinforce CVS as a promising marker to support MS diagnosis. Researchers now will call for larger, prospective studies with people suspected of MS, to confirm the clinical utility of this MRI signal.